Exchange and social distance

The dominant ethnographic approach in twentieth-century substantivist anthropology contrasts non-western gifting and exchange with capitalist, market-oriented trade in alienable commodities. Malinowski (1922) describes forms of exchange ranging from pure gifts to trade with increasing self-interest and "equivalence" as one moves towards the trade relationship. Mauss (1990 [1925]) attacks the notion of the pure gift and instead focuses on the temporal aspects of gift-giving, with the establishment of what are effectively ancient forms of credit. Further, Mauss focuses on the sociality of gift exchange with the idea that gifting can take hostile forms by inflicting obligations that the recipient may fear. Sahlins (1972: 191) subsumes the sociality of exchange relationships into a single trajectory with the concept of social distance. The "social distance" between exchange partners is a way of conceiving of the degree of familiarity and information transfer between producer and consumer of goods.

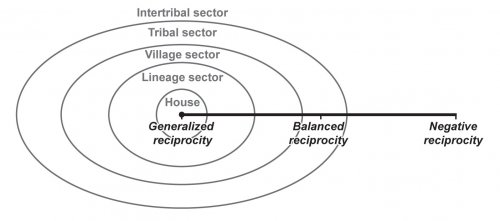

Figure 2-1. Varieties of reciprocal exchange (after Sahlins 1972: 199).

In Sahlins' classic taxonomy of reciprocity he identifies generalized, balanced, and negative reciprocity as a continuum from gift through exchange to haggling and theft, with explicitly different moral standards applying to transfers occurring in each sector. These modes of reciprocity were mapped directly on to increasing social distance originating in the household, although Sahlins was unspecific about the institutional forms of exchange, allowing for wide cross-cultural variation.

Besides the functionalist underpinnings of Sahlins' approach, one critique of his social distance model rests on his distinction between the role of the state and social relationships based on economic ties.

Because Sahlins is constructing a general theory, he is not obligated to deal with the refractory ethnographic data of one particular group. Hence, Malinowski's multiple heterogeneous categories of gifting never arise. In its place, Sahlins has a single Big Idea developed in the famous chapter on Hobbes and Mauss. The idea is that economics is politics for primitives. The understructure of human society, the default, is the chronic insecurity of Hobbes' "war of all against all." Primitives lack the state that is Hobbes' preferred remedy (Danby 2002: 24).

The result for Sahlins rests on a weak dichotomy between primitive|modern economic contexts that includes (1) primitive contexts where relations are mediated by social and economic relationships, and (2) modern contexts given over to the logic of neoclassic economics because commercialization and the circulation of alienable commodities are qualitatively different. Danby presents instead a "post-colonial critique [that] sees gift|exchange as yet another mapping of primitive|modern, an ultimately tautologous them|us split in which 'they' are various negations of what 'we' think 'we' are" (Danby 2002: 32). Anthropologists have sometimes followed this dichotomy where long-term investment and the establishment of social relationships in transactions is given over to the gift side, while exchange in alienable commodities is expected in complex, state level economies where exchange transactions are analyzed following the neoclassical approach and spot transactions are conducted in open markets.

In contrast, Danby argues that, if anything, one should expect greater temporal complexity and mechanisms for extending forward credit with greater social complexity.

Rather than building theory by pushing off against neoclassical exchange, let us put neoclassical exchange aside... the asocial spot transactions on the right-hand ends of [Sahlins' (Figure 2-1)] gift-exchange continua are also marginal to wealthy capitalist economies. Forward, debt creating transactions, embedded in social relations that often entail power, are central. Moreover, they are likely to be socially embedded in a variety of ways that should lead us to rethink the dichotomies between non-gift and gift (Danby 2002: 28).

Instead of framing the anthropological discussion of exchange in opposition to neoclassical approaches, Danby argues that the discussion should be reframed around institutions that underlie transactions in society and provide the long-term temporal milieu within which transactions occur. Temporality is particularly important when exchange is framed by production calendars based in agricultural cycles and by social calendars centered on gatherings and ceremonial occasions. By this standard, goods lying on the inalienable end of the continuum are fundamental to examining all economies in an anthropological light.