Variations on Modes of Exchange

Some scholars have built on Polanyi's four original modes of exchange, others have developed entirely new schema (Smith 1976). Earle (1977: 213-216) argues that Polanyi's (1957: 250) definition of redistribution as "appropriational movements towards a center and out of it again..." is vague and Earle observes that this definition is so broad that it could to apply to economic systems ranging from central storage of goods in Babylonia to meat distribution in band-level hunters. Earle advocates separating leveling mechanisms from institutional mechanisms, where institutionalized redistribution involves wealth accumulation and political transmission between elites across broad regions in the mode of peer-polity interaction (Earle 1997).

Andean political economy

Stanish (2003: 21) expands on Polanyi's system by describing political economy in the prehispanic Andes with deferred reciprocity taking the form of competitive feasting and political support (Hayden 1995;Stanish 2003: 21). Stanish observes that while there was an implicit or explicit (Service 1975) evolutionary sequence going from reciprocity to redistribution and finally to markets, more recent evidence suggests that these modes can co-occur and that the relationships are too complex to collapse into a single sequence.

Types of reciprocity

Sahlins (1972: 194-195) further elaborated on aspects of Polanyi's reciprocal mode with generalized, negative, and balanced reciprocity. Generalized and negative reciprocity are opposite ends of a continuum (see Figure 2-1, above). Generalized reciprocity refers to sharing, altruism, and Malinowski's "pure gift", while negative reciprocity is the attempt to maximize personal gain from the transaction through haggling or theft (Sahlins 1972: 195-196). Polanyi's basic modes of exchange have persisted in economic anthropology for almost fifty years. Some argue that Polanyi's modes of exchange are limiting in that they do not provide a means to analyze precapitalist commercial activity (Smith 2004: 84), however the benefit to Polanyi's exchange modes is that they are sufficiently general to be comparable cross-culturally and the three modes are discrete enough to be, in some cases, archaeologically distinguishable. Furthermore, if commercial activity is unlikely in the study region, as in the prehispanic south-central Andes, Polanyi's modes capture the necessarily economic variability.

Geographical characteristics

Renfrew (1975) considers trade as interaction between communities in terms of both energy and information exchange. Renfrew (1975: 8) tabulated Polanyi's schema as follows

|

Configuration |

Geographical |

Affiliation |

Solidarity |

|

|

Reciprocity: |

Symmetry |

No Central Place |

Independence |

Mechanical |

|

Redistribution: |

Centricity |

Central Place |

Central Organization |

Organic |

Table 2-3. Characteristics of reciprocity and redistribution (from Renfrew 1975: 8).

Renfrew follows with an exploration of the greater efficiency implied by central place organization in terms of material and information exchange. The universality of central place organization in the development of complex political organization worldwide has been called into question in pastoral settings. In the south-central Andes, anthropologists have proposed that alterative paths to complex social organization could have been pursued by distributed communities linked by camelid caravans with the anticipated central place hierarchy not occurring until relatively late, as proposed by Dillehay and Nuñez (1988) and in a different form by Browman (1981).

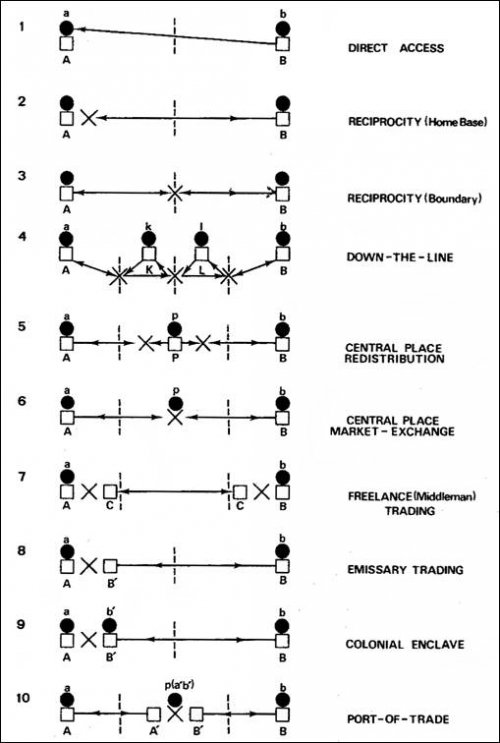

Renfrew has developed a graphical representation of the spatial relationships implied by each mode of exchange.

Figure 2-2. Modes of exchange from Renfrew (1975:520) showing human agents as squares, commodities as circles, exchange as an 'X', and boundaries as a dashed line.

The exchange modes depicted by Renfrew (1975:520), shown in Figure 2-2, efficiently convey the variety in organization represented by exchange relationships. In some regions of the world, such as the prehispanic south-central Andes, market-based economies are not believed to have operated which modifies one's expectations for the activities of traders. The full suite of these ten modes is not expected in any one particular archaeological context worldwide, but the figure serves to underscore the complexity of isolating particular types of exchange based on archaeological evidence. Furthermore, these modes are not necessarily mutually exclusive, as some of these modes may have been operating simultaneously unless restrictions on production, circulation, or consumption of goods were in place.