2.3.3. Site-oriented studies of exchange

As obsidian moved farther from its source, the size of the pieces traded progressively decreased and the relative value increased. ...Small blades were obtained simply by smashing a large block with a stone, while in time blades were broken into smaller fragments to obtain newly sharp edges (Harding 1967: 42).

Establishing consistent links between the types of social structure and the forms and organization of production in association with exchange was the approach taken by Ericson (1982) and, most explicitly, by Torrence (1986). By investigating the standardization and error rates in blade reduction strategies at obsidian production sites on the Greek island of Melos, Torrence was able to evaluate the degree of specialization involved in the quarrying and production of obsidian at the source.

In her review of archaeological site-oriented studies of exchange, Torrence (1986: 27-37) uses a few major themes to characterize site-oriented investigations. These themes include measures of abundance, source composition percentages, and the variability in archaeological context and artifactual form of import.

Measures of abundance

Investigators have compared changes in the abundance of non-local material with domestic goods that are assumed to represent population. The ratio of the weight of obsidian to volume of excavated dirt (as shown in Figure 2-5) or as a ratio of weight of ceramics (as a proxy measure for population) has been used in a number of studies in Mesoamerica (Sidrys 1976;Zeitlin and Heimbuch 1978: 189). In studies of Near Eastern obsidian exchange Renfrew (1969;1977) develops indices for the presence of obsidian based on counts and weights per phase and per excavated cubic meter, and he also uses the count of obsidian artifacts as a percent of the total lithic assemblage count. Renfrew qualifies his conclusions due to a lack of consistency in the data, but he estimates that the total quantity of to arrive at the site was relatively small and he observes a decrease in obsidian at Deh Luran sites. Working at the Olmec site of San Lorenzo Tenochtitlan, Cobean et al. (1971) develop an index that compared the number of obsidian flakes, blades, and total debitage with grinding stones and slabs for each phase at the site, with the abundance of grinding equipment serving as an estimate of number of households. The authors interpret the increasing index of obsidian to grinding slabs as evidence of a gradual rise in "prosperity" for individuals at the site, though they only briefly explore the implications for changing exchange relationships (Cobean, et al. 1991).

In Torrence's examination of the aforementioned studies she concludes that "the major difficulty with studies of consumption based on measures of resource abundance is that they lack the necessary linking arguments between patterns of consumption and type of exchange" (1986: 28-30). She states that what is needed for site-level studies of abundance and exchange is "a series of arguments describing how resource use will respond to specific types of exchange" akin to the explicit connections that Renfrew developed on the regional scale between distance decay and forms of exchange.

Site level composition from multiple sources

When raw material is available to consumers from several competing sources, investigators have used the relative quantity of materials from the different sources at individual sites to gain insights into ancient exchange. Broad exchange relationships are frequently inferred from the presence of obsidian from a distant source. When material from several rival obsidian sources are represented, either strongly or weakly, in different phases at a site, the cause of the changes in representation is often attributed to shifts in the geography of regional political or economic relationships. Geographical explanations are invoked when there is a clear deviation from the LMD, and yet evidence of significant in-situ political change is not found in investigations among studies in Mesoamerica (Zeitlin 1978: 202;Zeitlin 1982) and the Near East (Renfrew 1977: 308-309).

Changes in the mechanisms of exchange, rather than simply geography, are attributed to changes in the source composition from different sources when socio-political changes are perceived by investigators. Studies have inferred redistribution occurring when sites that act as central places (Christaller 1966 [1933]) at the top of the settlement hierarchy have disproportionate quantities of non-local materials irrespective of their distance from the source. This phenomenon has been discussed for Tikal (Moholy-Nagy 1976: 101-103;Sidrys 1977).

When sourcing studies are conducted at the scale of the household unit, though it is often labor intensive and costly to conduct proveniencing studies to an extent that are statistically meaningful, it is possible to discern convergence patterns that can be connected to exchange mechanisms (Pires-Ferreira and Flannery 1976;Santley 1984;Torrence 1986: 35). The most common application of evidence of variability between households in source composition is to infer redistribution from the presence of low inter-household variability in source composition.

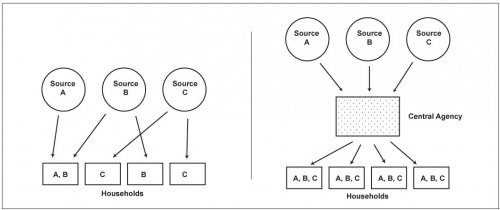

In a reciprocal economy where individual households negotiate for their own obsidian, we would expect a good deal of variation between households, both in the sources used and the proportions of obsidian from various sources. Conversely, in an economy where the flow of obsidian is controlled by an elite or by important community leaders, who pool incoming obsidian for later distribution to their relatives, affines, or fellow villagers, we would expect less variation and more uniformity from one household to another (Winter and Pires-Ferreira 1976: 306).

The concept is been depicted in a graphic from.

Table 2-4. Household composition of raw materials should vary with different types of exchange. On the left, individual households acquire source materials more directly, on the right pooling and redistribution results in greater inter-household consistency in raw material composition (Winter and Pires-Ferreira 1976: 311).

This approach was influential in Mesoamerica (Clark and Lee 1984;Santley 1984;Spence 1981;Spence 1982;Spence 1984 ) where the technology of transport did not change significantly except for perceived changes in the form of boat technology. Transport changes could significantly impact the inter-household diversity of source composition in places, such as the Near East, where caravan exchange networks followed from the domestication of pack animals (Wright 1969). The impacts of caravan exchange on artifact variability has long been discussed in the Andes (Dillehay and Nuñez 1988;Nuñez and Dillehay 1995 [1979]), although household-level sourcing data has not been available to date.

Variation in site-level contexts and artifact form

Intrasite variability in lithic distributions, and the morphology of those artifacts, can shed light on exchange patterns. Several projects in Mesoamerica have inferred redistribution as the mechanism of exchange when concentrations of non-local lithic materials at major sites point to debris associated with specialist workshops and other kinds of intrasite use of space. Blade manufacturing debris has been used in this manner at Tikal (Moholy-Nagy 1975;Moholy-Nagy 1976;Moholy-Nagy 1991;Moholy-Nagy 1999), the Basin of Mexico (Sanders, et al. 1979), and Teotihuacan (Spence 1967;Spence 1984).

The proportion of artifact forms of a non-local material in a single site has been used to characterize mechanisms of exchange. This approach has proved useful with obsidian exchange in places where distinctive reduction strategies are associated with finished artifact form, such as blade technology, and these strategies can be recognized in lithic material found in consumption sites. Winter and Pires-Ferreira (1976: 309-310), working at two sites in Oaxaca, argued that blades of high quality, non-local obsidian were introduced to the sites in finished form and that this constituted evidence of elite pooling for prismatic blade reduction followed by redistribution to local sites. The higher quality material was transformed into more valuable artifact forms in workshops located outside of their study area, and then in the Oaxaca sites the presence of these artifacts that were apparently the result of contact with elite spheres of exchange, was interpreted as evidence of redistribution of the finished artifacts. The sourcing and exchange work of Pires-Ferreira has come under some criticism because in her initial proveniencing study she only used two diagnostic chemical elements, and more recent analyses suggest that many of her sourcing attributions are incorrect (Clark 2003: 32). Further, Sheets (1978: 62) argues that the edges of prismatic blades are too fragile to have been transported in completed form (Clark and Lee 1984: 272).

Systematic studies of the intrasite contexts and artifact form of non-local material have the potential to provide insights into exchange and social structure. Intrasite spatial patterns can be investigated in combination with both quantitative data stemming from geographical distances and artifact abundance, and with qualitative data inferred from artifact form and technological aspects of production (Torrence 1986: 36). These kinds of intrasite patterns are susceptible to distortion by dumping patterns and intrasite studies must be sensitive to the problems of conflating material from workshop refuse, household middens and construction fill (Moholy-Nagy 1997).

In a useful review of Mesoamerican obsidian studies Clark (2003: 32-39) summarizes major advances in provenience and trade models, and highlights important avenues for improvement. One important observation made by Clark is that in archaeologists' efforts to design systematic approaches to exchange, early studies failed to distinguish "power as energy and power as legitimacy" (Clark 2003: 38). It could be argued that these forms of power are largely comparable, as the ability to procure, display, and redistribute non-local goods demonstrates power in both energy and in prestige. However, as was emphasized by substantivists in their discussion on the inalienability of certain products, the value of particular status items rests precisely in their incommensurate nature.

Sanders and Santley's (1983) proposal that special goods were returned to Teotihuacan in exchange for obsidian products, and that these were cashed in for corn from the fringes of Teotihuacan's domain in hard times, fails to appreciate that once symbolic goods circulate like economic goods among the hoi polloi such goods lose any legitimizing powers (Clark 2003: 38).

A framework for investigating prehistoric exchange must negotiate between these features of the archaeological record. Material evidence of long-distance exchange is abundant and easily measured, but interpreting the significance and perceived value of these non-local products in the social and political context of their consumption is the measurement of greatest relevance to comprehending the role of exchange over time.