3.1. Andean Economy and Exchange

The Andes present a valuable opportunity for examining anthropological models of economy and exchange in prehistory. Distinctive historical aspects of Andean development, including the emergence of pristine states at high altitude, the administration of vast empires without a formal system of writing, and the wealth of ethnohistoric data provided by Spanish chroniclers, offer important research problems for economic anthropology. This study investigates the procurement and circulation of obsidian from the Chivay source in the south-central Andes during a broad time period that includes major shifts in the economy and in socio-political organization.

Throughout prehistory, the long, narrow Andean cordillera presented distinctive challenges to human groups that were addressed through a variety of technological and social strategies. Here, a focus on lithic raw material procurement and exchange permits obsidian circulation to serve as an indicator for particular types of regional interaction.

Exchange has a complex role in mediating human relationships over distance (see Section2.2.2), and in the south-central Andes, obsidian appears to have served as both a political tool and relatively ordinary aspect of economic activity. In part, the persistence of exchange in herding regions reflects lack of autarky among the dedicated pastoralists; they require vegetative and agricultural products, and such items are widely available in the sierra and foothills. In reference to the early development of long distance caravan networks in the altiplano, David Browman (1981: 413) notes "[t]he trade in consumables is less spectacular than the trade in luxury items, and more difficult to detect archaeologically, but it was much more important to the average altiplano inhabitant." In other words, due to the environmental contrasts in the Andes, relatively mundane consumables like salt, ajipeppers, and even coca leaf could precipitate a low-level but persistent demand for exchange of goods between adjacent ecological zones and, in some cases, across larger distances.

A central point of the following discussion is that wide-ranging exchange networks, apparently organized at the level of the household and facilitated by caravan transport, are a persistent theme in the south-central Andean highlands. These networks do not integrate easily with the exchange typologies presented above (Section 2.2.4), and this form of articulation is sometimes seen as irrelevant "background" reciprocity in models of early competitive leadership. However, this distributed mode of integration may have served as an early foundation for subsequent political organization in the region. This study focuses on obsidian procurement and distribution and infers that other goods were also being transferred along these networks. While the simple assumption that evidence of obsidian circulation is analogous to prehistoric trade in a multitude of other more perishable goods is problematic, the persistence of obsidian exchange in the south-central Andes is compelling evidence of generalized contact over distance.Andean approaches to regional economy are reviewed here in order to examine the distribution of obsidian and other goods through diverse mechanisms of procurement and exchange.

3.1.1. Economic organization and trade in theAndes

In a cross-cultural perspective, Andean exchange relationships throughout prehistory exhibited characteristic organizational traits of societies dwelling in mountain ecological zones; although in the late prehispanic periods distinctive features of inter-zonal control emerged in the south-central Andes. There is general consensus among Andeanists that the mechanisms of merchantilism and market economies - prices reflecting supply and demand - did not exist in the late prehispanic south-central Andes[2].

Polanyi's substantivist economic typology based on peasant households in non-capitalist settings is still widely used in the Andes with some modification.

Reciprocity, redistribution, and non-market trade are the institutional means by which indigenous Andean economies operate. All evidence points to the overriding fact that true market systems did not operate in the central Andes, as they did in central Mexico and in a number of complex societies of the Old World. Exchange did exist on a massive and pervasive scale, however, and the concept of administered trade is the superior means of understanding this phenomenon in the prehispanic central Andes. Trade existed, but it was not one based on market principles. Virtually all cases of trade were administered by some corporate group, constituted along sociological (kinship) or political lines (Stanish 1992: 15).

The major modes of economic interaction will be reviewed below. Finally, the closing section of chapter 3 will explore more specific material expectations of how each of these economic modes may appear in procurement areas such as the Chivay obsidian source.

Direct Access

Direct household procurement of goods is largely structured by the geographic relationships between consumer residence and a given resource. Access to products from complementary ecological zones by consumers who undertake a personal voyage to acquire and gather those goods is a form of direct access. For resources that are widely distributed in ecological areas or along altitudinal bands, direct access is a recurring theme in Andean prehistory. The procurement of unique or unevenly distributed or resources, such as salt or obsidian, is a different configuration entirely in a vertically organized region like the Andes, because distant consumers are forced to articulate with production areas far beyond their immediate and complementary neighbors in an altitudinally stratified exchange relationship. This kind of multiethnic, direct household procurement for salt occurs in the Andes to this day (Concha Contreras 1975: 74-76;Flores Ochoa 1994: 125-127;Oberem 1985 [1974];Varese 2002).

Direct access by foragers was the first mode of procurement in the Andes, and this acquisition mode probably dominated in Early Holocene prior to the population growth that permitted the development of reciprocity networks. The procurement of raw materials in a manner that is incidental to other subsistence activities is a more efficient means of acquiring these goods, an activity described as "embedded procurement" by Binford (1979: 279). Communities, ethnic groups, and even prehistoric states appear to have maintained direct access to resources in other zones, and (as is stipulated by the definition of the direct accessmode) this kind of articulation is for direct consumption or redistribution on the level of the corporate or state entity. This is part of a much celebrated pattern in Andean research, a feature known as vertical complementary (Murra 1972), a topic that will be returned to in more detail below. Direct access by states to unusual sources of raw material such as metals and minerals are well documented in the Andes. These include as Inka mine works, and distinctive Inka artifacts and architecture are commonly encountered in association with the procurement areas. In access between herding and agricultural sectors, there is also an ethnographically documented direct access mode described as "ethnic economies". In this direct access mode, ethnic groups will control parallel strips of vertical land holdings, and sometimes non-contiguous tracts, ranging from lower agricultural zones to high puna that may lie several thousand vertical meters above. This pattern is documented on the eastern slope of the Andes for the Q'eros of Cuzco (Brush 1976;Flores Ochoa, et al. 1994) and several communities in northern Potosí in Bolivia (Harris 1982;Harris 1985). The important concept of the direct access organization is that entities that were consuming the goods were directly responsible for acquiring them. If there is inter-household barter or transfer of any kind, then the arrangement likely belongs to a type of reciprocity relationship.

Reciprocity

The institution of reciprocity is important in all societies, and in the contemporary Andes reciprocal relationships are elaborate and permeate village life. It is an arrangement for the transfer of labor or goods that is organized without coercive authority between entities equal in status, although sometimes disputes are settled by community leaders. Andean labor reciprocity includes agricultural work, roof raising, canal cleaning, terrace building, and other services; as such, reciprocity structures the traditional village economy in the Andes (Alberti and Mayer 1974;Stanish 2003: 67). These kinds of reciprocal arrangements are frequently delayed, although compensation can be accelerated through recompense in products. For example, a herder might bring a caravan down to a farming area in the lower valleys and spend some days contributing labor to the agricultural harvest in exchange for some portion of the yield.

In many premodern economic transactions relationships of balanced reciprocity structured these arrangements. Two forms are likely in the Andes, that include (1) a multitude of small, household exchanges creating "down-the-line" artifact distributions (see Figure 2-2), presumably this type of exchange is responsible for the long distance transmission of small, portable goods for much of the pre-ceramic period. A second form consists of (2) barter exchange relationships with regular long distance caravans that articulated with settlements, and perhaps at periodic fairs, that transported goods over potentially greater distances. This mode would effectively consist of unadministered trade. The institution of reciprocity will be explored in more specific contexts below.

Redistribution

The basis of relations between political elites and non-elites in the prehispanic Andes was shaped by redistribution. In Andes during the later prehispanic period, redistributive mechanisms linked elites to non-elites through the redistribution of consumables like coca, and feasts of food and chichabeer in exchange for labor and political support. "The manipulation of redistributive economic relationships among the elite and their retainers, most notably of exotic goods and commodities, stands at the core of the development of Prehispanic Andean complex societies" (Stanish 2003: 68). Often these surplus goods were produced through efficient mechanisms orchestrated by elites, and the benefits and prestige derived from these surpluses would be accrued disproportionately by political leaders.

The central collection of goods for redistribution or use by the state includes taxation which, in the Inka period, was through mit'alabor. With respect to the exchange of lithic raw materials, Giesso (2003) argues that at Tiwanaku household stone tool production was a form of taxation. Giesso cites ethnohistoric evidence referencing the Inka period and argues that the household knapping of projectile points could have contributed to the provisioning of the state armory. The means by which non-local material arrived in the Tiwanaku homeland is unclear, but in the Inka case the raw material was acquired locally or it was provided by the state (Giesso 2003: 377). Earle (1977: 215) argues that redistributionshould be considered as two major groups with leveling mechanisms on one side and complex institutional mechanisms for wealth accumulation on the other (see Section 2.2.4).

Administered Trade

Non-market administered trade was another major means of transfer in the prehispanic south-central Andes. Building on Polanyi's classic definition of non-capitalist economic types, Charles Stanish (2003: 69) describes a form of elite-administered, non-market trade that was capable of procuring non-local goods and that provided wealth to elites as follows. Garci Diez's Titicaca Basin visita, a 16thcentury Spanish census document (Diez de San Miguel 1964 [1567]), describes how local elites in the Lake Titicaca Basin would have their constituents organize llama caravans for trading expeditions to adjacent regions. In neighboring areas such as the Amazon basin to the east, the Cusco valley, and western slope valleys, agricultural goods such as corn, fruits, and other products were sweeter, faster growing, and more abundant than in the Titicaca Basin. The colonial visitaindicates that, based on the colonial currency, corn in the Titicaca Basin was worth 5.7 to 6.9 times the amount that it was worth in the Sama valley (an area in modern-day southern Bolivia) where it was abundant. Stanish (2003: 69-70) argues that administered trade benefited elites because they were able to appropriate this difference in value, and through feasting and other ceremonial functions, a portion of this wealth was redistributed to commoners. It is important to mention that these same colonial sources indicate that the commoners also organized trading ventures and would take advantage of these elite-organized journeys to conduct private barter exchange on the side. With reference to herders conscripted into elite orchestrated trade caravans "those in Lupaca country 'who had their own cattle [cargo llamas]' (Diez de San Miguel 1964 [1567], f. 13v) went to the coast and to the lomas to barter on their own. …the maize growers on the irrigated coast were eager for the highlander's animals, their wool and meat" (Murra 1965: 201). Thus, elites organized large caravans and apparently possessed the surplus wealth and the camelid caravan animals in advance to initiate the trading expedition, but the herders that they conscripted also engaged in household-level barter. For the elites, their organizational efforts earned them significant wealth and status for a relatively modest outlay of costs. For the herders, it appears that they were able to embed household economic transactions with their mit'alabor service by conducting their side barter activities. Apparently, even the powerful Lupaca elite had to concede some independent trade activity to their caravan drivers. What, then, of the relationship between caravanerosand elites during earlier periods, when elites probably had less consolidated power than during the contact period?

The evidence suggests that "administered trade" was not the first form of long distance caravan exchange. As mentioned above, relationships of balanced reciprocity have long served to articulate herders with those living in complementary ecozones such as sierra agriculturalists, coastal fishers, and residents of the eastern lowlands. But the long distance transport of diffusive goods like obsidian are well-demonstrated and form a continuous network configuration that contrasts with the segmentary, vertically organized exchange between valley and puna (Figure 2-3). Archaeological distributions (Browman 1981;Burger, et al. 2000;Dillehay and Nuñez 1988;Nuñez and Dillehay 1995 [1979]) and contemporary ethnoarchaeological studies (Lecoq 1988;Nielsen 2000;West 1981) attest to the capacity for small scale, household-level organization of multi-week caravan expeditions. This evidence suggests that there were probably at least two major types of long distance caravans operating from the Late Formative onwards. The question then becomes: what was the relationship between household-level caravans and elite-administered trade? Did elites co-opt functions that were previously coordinated on the household level? If elites acquired control of some segment of caravan traffic, what strategies did elites use to wrest control from caravan drivers that, the evidence suggests, were very independently-minded people (Browman 1990: 419-420;Nielsen 2000: 517-520)? These questions concerning the origins and configurations of regional interaction in the south-central Andes are at the center of this discussion of changes in obsidian procurement and the regional circulation of goods in prehistory on the perimeter of the Lake Titicaca Basin.

3.1.2. Economy and exchange in mountain environments

Cross-cultural studies of human adaptation to mountain environments have revealed a number of common features between production strategies employed by people in the Andes, the Himalaya, and the Alps (Funnell and Parish 2001;Guillet 1983;Rhoades and Thompson 1975;Tomka 2001). These commonalities in adaptation to mountain settings include:

- Both specialized and mixed procurement systems are found, but there is a predominance of mixed systems.

- Specialized procurement systems are interconnected through regional exchange.

- Land holdings by a particular social unit can be non-contiguous and distributed across multiple ecological niches.

- In extensive procurement zones, such as grazing areas, land tenure is communal, whereas in intensive procurement, such as irrigated farmland, tenure is often family based.

These strategies are responses to characteristics of mountain settings that include altitude-based biotic ecozones, limited productivity in any single zone, and risk to herding and farming in production activities.

These regular features of production in mountain settings provide a comparison against which to evaluate procurement strategies in the Andes. A number of characteristics of production common to mountain environments have been inappropriately conceived as exclusively Andean in an essentialist tradition referred to as lo andino (Starn 1991;Van Buren 1996), while conversely others have sought to impose Andean models on regions where the model does not necessarily apply (Goldstein and Messerschmidt 1980). These models of regional interaction in mountain environments, both in Andean and general geographical models, can be contrasted with regional distributions of raw materials. Obsidian and other raw materials circulated widely in the Andes, and the spatial patterns described by these materials, may be examined in light of other regional patterning like stylistic distributions, as well as economic models of regional interaction.

Vertical complementarity

The contrasting ecological zonation found in low-latitude mountain regions worldwide has resulted in distinctive social configurations that appear to reduce risk, broaden the selection of products available in a given zone, and provide opportunities for strategic advancement by particular individuals or groups. These configurations have been investigated in two broad sets by Andeanists. First, there are a number of scholars who address vertical complementarity as a general process that is comparable with other mountain regions of the world. Second, there is a particular configuration known as "Vertical archipelagos" first described by John Murra (1972) that has been widely discussed in the Andean literature.

Verticality writ large

Vertical complementarity encompasses a variety of strategies for the problems posed by human use of resources at different scales, and by the broad natural diversity across relatively small distances in mountain environments (Aldenderfer 1993;Masuda, et al. 1985). These problems of articulation are addressed through mobility, through direct control of different zones by a single group, by mutualism between residents of different zones, and through a variety of exchange relationships. Vertical organization has been recorded among modern Quechua and Aymara communities (Brush 1976;Brush 1977;Flores Ochoa, et al. 1994;Harris 1982;Harris 1985;Platt 1980).

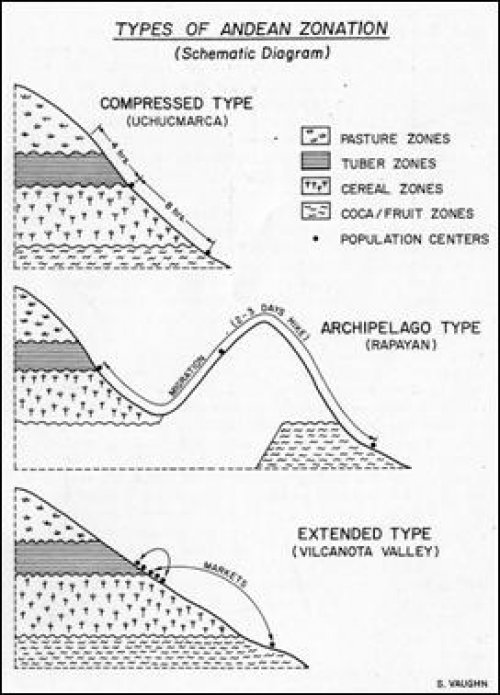

Figure 3-2. Contemporary types of Andean zonation (Brush 1977: 12 ).

Based on contemporary observations, Brush (1977: 11) describes three systems:

- the archipelago type, or vertical complementarity, as conceived by Murra;

- a compressed type, where a single village can access and control all resources without resorting to means of long distance control;

- the extended type that corresponds to horizontal complementarity.

On a more localized scale it is possible to see vertical control strategies within a particular valley in a mixed agropastoral strategy that has been called "compressed archipelago" (Figure 3-2). In the central part of the Colca valley on the western slope of the Andes in Arequipa, Peru, Guillet describes vertical household relations.

To what extent do households integrate both puna pastoralism and valley farming into their production and exchange strategies? First, most households residing in the puna tend to specialize in herding and do not have agricultural fields that they cultivate directly. Similarly, many village households neither belong to family surname groups with access to puna pastures nor count themselves among those who have gained control of communal pastures ( botaderos) on the slopes behind the village. Households that follow such specialized strategies must perforce use the exchange nexus to obtain complementary products (Guillet 1992: 133).

Additional evidence for micro and macro vertical complementarity is discussed in the context of the Colca valley (Casaverde Rojas 1977: 172;Málaga Medina 1977: 112-113;Pease G. Y 1977;Shea 1987: 71).

Vertical complementarity can viewed as an anthropological principle that describes the propensity for social groups in mountain environments, from foragers to state societies, to geographically broaden their social and economic base and reduce risk by exploiting a variety of environmental settings (Aldenderfer 1993;Guillet 1983;Salomon 1985). Salomon (1985: 520) presents complementarity strategies in prehispanic Ecuador as varying in two dimensions.

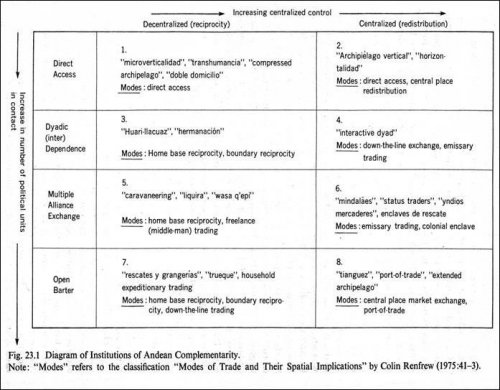

Figure 3-3. Diagram of institutions of Andean complementarity (from Salomon 1985: 520). Numbered modes reference the "Modes of Trade" in the figure from Renfrew (1975: 41-43 ) shown in the previous chapter as Figure 2-2.

One is between decentralized systems based on reciprocity, and the other is based on centralized systems of redistribution. There is an underlying neo-evolutionary correspondence implied in many of these models, as chiefdoms and states are believed to have been responsible for the network convergence perceived in redistributive systems, however it is important to observe that due to the variety in products, social relationships, and economic configurations, it is likely that a great many of the institutions presented in Figure 3-3 occurred simultaneously, and in general there is no direct correlation between confluence and evolutionary typologies. Another important dimension involves the number of political units participating in the interaction ranging from direct access, dyadic relations, exchange systems and open barter. The vertical complementarity literature in the Andes is valuable for considering prehispanic exchange relationships in that it has compelled a number of scholars to explore explicitly the relationship between ecological zonation, production, and social organization.

Vertical archipelagos

The work of John Murra on vertical complementarity has been among the most influential ethnohistoric studies in the Andes. The premise of the vertical archipelagos model is that the rapid altitudinal change along the flanks of the Andes produced a pattern where social groups residing in non-contiguous ecological strata formed distinct communities that developed around intensified production in these strata. Polities and ethnic communities sought to control a variety of these resource pockets following the Andean ideal of self-sufficiency.

Murra's (1972) seminal article distilled observations from ethnohistoric sources, in particular the visitacensus Garci Diez (1964 [1567]) of Chucuito in Puno, conducted only 35 years after the Spanish invasion. Murra showed that late prehispanic altiplano societies obtained direct access to products from a variety of ecological niches through this practice, and that the strategy was a guiding model of organization in some Andean polities (Salomon 1985). According to Murra (1985) the principal characteristics of the vertical archipelago model can be summarized as follows:

- Ethnic groups aimed to control numerous "floors" or ecological niches in order to exploit the resources that are found there and maintain self-sufficiency. As a consequence, powerful polities residing in the altiplano had considerable wealth in pastoral herds but also controlled land on both the western and eastern flanks of the Andes.

- The population was concentrated on the altiplano and those living in the peripheral 'islands' maintained continuous social and economic contact with the core region.

- The institutions of reciprocity and redistribution guaranteed that those living in 'islands' maintained the rights to products available in the center. These rights were defined through kinship ties that were ceremonially reaffirmed in the center.

- A single 'island' could be shared by different ethnic groups, though the coexistence could be tense.

- The relationships and functions of these colonies changed through time and may have become more exploitative. They are perhaps an antecedent to the mitimaqstrategy of the Inka empire.

While a chiefdom level of organization and centralized power is a principal characteristic of the Late Intermediate polities that practiced vertical complementarity in the period examined by Murra, the concept was been explored and expanded by archaeologists in the subsequent decades. In Murra's original description, verticality referred explicitly to direct control of a diverse resource base without engaging in trade with other ethnic groups, thereby preserving what Murra (1972) has described as the ancient Andean ideal of economic self-sufficiency that permeated Andean society and ideology far beyond his Lupaca case study. Stanish argues that Murra was explicit about excluding exchange processes, in part, because he perceived "a structural linkage between exchange and markets" (1992: 15). As prehispanic market mechanisms were absent in the south-central it was believed that barter and exchange were also of minimal importance and other means of articulation, such as direct control, were emphasized. Murra, however, later modified the definition to include specialized exchange centers, a change which Browman (1989: 324) argues confuses the issue because it subsumes a variety of processes into a single model.

On a theoretical level a further limitation of the original 'verticality archipelago' model lies in its adaptationalist orientation (Earle 2001).Adaptationist models of exchange and regional control have their basis in Service's (1962) proposal that these arrangements arise from environmental diversity, and then chiefs emerge to administer and redistribute goods produced regularly by their retainers.As observed by Van Buren (1996: 346), the archaeological origins and perpetuation of the archipelago pattern was founded on the assumption that groups benefit, as a whole, from the control of multiple tiers and the ecological resources that are produced in those archipelagos. As mentioned above in the discussion of administered trade, colonial documents emphasize the independence of commoners and the ability of subjects to practice subsistence barter, a pattern that leads authors to suggest that the vertical archipelagos pattern may have had more of a political basis than a foundation in ecological and subsistence practices. The ultimate roots of such a system may lie instead in the capacity of the rulers of such groups to organize larger scale trade and convert the value differential between products in the different ecological zones into political prestige through feasting and ceremony (Stanish 2003: 69-70).

Horizontal complementarity

Soon after Murra published his 1972 paper about vertical complementarity, researchers began noting that vertical complementarity is only one of a number of strategies employed in the Andes. A different kind of geographical interaction pattern, one that stays within broad regions such as the altiplano or the littoral, has been called horizontal complementarity. Contrasted with Murra's vertical complementarity model, in horizontal complementarity polities would directly control many parcels in a given niche. Here, the adaptationalist argument is somewhat less obvious since a horizontal complementarity strategy seems redundant unless particular resources were only available in one sector of a given horizontal territory. This phenomenon could reflect a cultural mechanism for the continued social integration of communities distributed widely across a vast region. An analogous situation can be observed in the culturally-constructed Yanamamö trade for ceramic wares, maintained to provide a social catalyst for villages to come together for feasting and marriage-making, despite the risk of conflict and treachery (Chagnon 1968).

Relations of horizontal complementarity between coastal valleys have been observed on the littoral (Netherly 1977;Rostworowski 1977;Shimada 1982), and for the higher altitude altiplano area where this kind of organization is referred to as the "altiplano mode of economic integration" (Browman 1977) and, to a lesser extent, the modern "extended type of Andean zonation" (Brush 1977: 12-16;Gade 1975). The extended type takes place in regions of expansive, contiguous production where exchange forms the basis for circulating products from other zones. In the expansive altiplano where there are fewer impediments to travel and, with the domestication of camelids, relatively low transport costs with cargo animals, materials may have been conveyed over substantial distances.

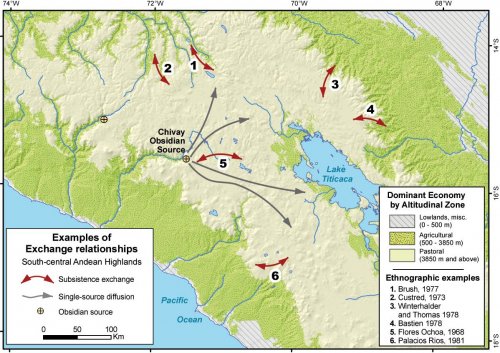

Figure 3-4. Subsistence exchange for products by ecozone versus single-source, diffusive goods.

A general schematic of these contrasting relationships is shown in Figure 3-4. While there is a great deal more complexity and variability to economy and exchange than is communicated in Figure 3-4, for example tubers are grown in the high elevation zones and herding does occur below 3800 masl, the purpose is to highlight the contrasting network characteristics. These two characteristics include

(1) Subsistence exchange.The acquisition of products available by zone contrasts

(2) Diffusive.The network for goods that radiate diffusively, such as obsidian and salt.

While the mixed agropastoral strategies are also very common, particularly in ecotone areas such as the puna rim, the subsistence exchange that articulates dedicated pastoralists with agriculturalists has been documented ethnographically in many studies of which only a selection are shown in Figure 3-4 (Bastien 1978;Brush 1977;Custred 1973;Flores Ochoa 1968;Palacios Ríos 1981;Winterhalder and Thomas 1978).

Ecological complementary has long served to transfer goods between ecozones, however the movement of goods laterally through areas of homogeneous resources, such as horizontal complementarity across the puna, implies other mechanisms of transfer. In addition to strategies described previously, it has been proposed that large periodic markets are a possible solution to the problems of social and economic integration among agropastoralists living in widely distributed settlements.

Browman (1990: 405-411) reviews the evidence for prehispanic and colonial period markets in the Peruvian and Bolivian altiplano. The colonial period aggregations in the Andes are products of historical circumstances, however Browman's evidence suggests that periodic fairs in some form were a feature of the prehispanic economy. While evidence concerning the actual goods exchanged at periodic fairs during the prehispanic period is scarce, these events could have been an effective way for obsidian to have been distributed in highland Peru and these fairs will be discussed in more detail below. Seasonal or annual gatherings are also ethnographically known among foragers in arid regions of the world with low population densities (Birdsell 1970: 120;Steward 1938). Social aggregations in some form can be expected to date back to the foraging period and these aggregations probably included, among other activities, the exchange of goods.

Evidence for barter, markets, and marketplaces in theAndes

"They did not sell… nor did they buy… they thought it was a needless operation" and all universally planted what they needed to support their households and thus did not have to sell foodstuffs, nor raise prices nor did they know what high prices were…(Garcilaso 1960 [1609]: 153; cited in Murra 1980: 142).

Was obsidian exchanged through a market system reflecting supply and demand in the prehispanic Andes? Were exchange specialists present in the prehispanic Andean highlands? If so, when did they appear and what did they transport? While extensive exchange has been documented in the prehispanic Andes, it is widely believed by Andeanists that exchange in the prehispanic central Andes was not based on market institutions. Building on the typology developed in Chapter 2 following Renfrew(1975)and Salomon(1985), differing degrees of specialization and independence can be expected to have existed among actors in exchange relationships (Figure 2-2andFigure 3-3). If specialized traders were present in prehispanic Andes, how did they interface with state authority during the Middle Horizon and Late Horizon, and what was their position during periods of regional conflict like the Late Intermediate Period?

Much of the evidence supporting the alleged lack of market-based exchange is derived from studies of Inka economic organization, where ethnohistorical accounts and archaeological datasets converge. A great deal has been written on the topic of Inka economy, and obsidian exchange was relatively diminished during this period, therefore this discussion will be limited to a few relevant issues regard exchange specialization. Several of the sixteenth century chroniclers are clear that while barter was widespread, the barter values of goods did not reflect fluctuations in supply and demand as in a market economy. However, the lack of consensus on the issue of markets and commerce during the Inka period stems from inconsistency in the cronistasthemselves. As reviewed by Murra(1980: 139-152)and LaLone(1982)the denial of a market exchange by Garcilaso de la Vega (quoted above) can be contrasted with numerous accounts of large and small markets, and a long tradition of barter exchange of various types.

The issue of Late Horizon marketplaces and market exchange is explored here because one of the principal questions that may be considered with changing obsidian distributions through time is the possible role of commercialism in prehispanic Andean exchange. The appearance of exchange specialists, such as freelance caravans moving certain commodities and responding to the changes in barter values that result from surpluses and shortages, would have presented a mode of transport distinctive from that of local reciprocal exchange or regional or state redistribution.

The vertical archipelago model functioned as an alternative to trade for goods from neighboring areas because "regional differences in production were, by preference, handled by means of colonization instead of through barter or trade."(Murra 1965: 201). As mentioned, Stanish argues that Murra initially excluded exchange mechanisms because of a perceived association between exchange and market economies. Further it can be argued, building on Appadurai(1986: 33), that in certain contexts of ranked or stratified societies with elaborate redistribution mechanisms, market systems of exchange represent a threat to the centralized ideological power of redistribution. "There is great advantage to leaders who are able to portray their resource-control strategies as reciprocity, redistribution, and generosity. Non-centralized resource-control strategies are, by definition, not 'control' strategies"(LaLone 1982: 296). If centralization is a principal determinant of state control on market exchange, were the peripheries involved in greater numbers of barter transactions?

Merchants in the Andes: Late Prehistoric and ethnohistoric evidence

Coastal Trade

The strongest evidence for merchant specialists in the Andean region comes from relatively peripheral areas of the Inka Empire, from the Pacific coast of what is now Peru, and from the coast and highlands of prehispanic Ecuador. The coastal Late prehispanic traders of Chincha, near the Paracas peninsula, have been described as consisting of 6000 merchants who traded in Cusco, among the Colla (and presumably the Collagua), and in Ecuador, but little is known about how these expeditions were organized(Patterson 1987;Rostworowski 1976;Rostworowski 1977;Sandweiss 1992). LaLone(1982: 308)notes that Rostworowski was not able to connect Chincha traders with marketplaces despite her assertion that these represented commercial exchange. Sandweiss(1992: 10)believes that Chincha trading expanded a great deal under the Inka following the Inka conquest of the Chimu to the north.

Coastal products such as spondylous and other goods were known to have been transported in large balsa rafts. There are numerous contact-period accounts of merchants plying the Pacific littoral beginning with the renowned loaded boat of balsa logs encountered off the coast of Ecuador by Pizarro on his second trip south, several years before the actual Spanish invasion of the Andes(Hemming 1970;Murra 1980: 140). The boat had a crew of 20 and had a small cabin and cotton sails. Murra is confident the boat was an Inka "registry" because the crew knew Quechua and a few were captured by the Pizarro's army who later used them as interpreters. While the Spanish paid particular attention to precious metals, the contents appear to have contained wealth goods including gold and silver ornaments, bracelets and anklets, headdresses and mirrors, and a great deal of cotton, wool and rich embroidery. A small weighing scale as well as a great deal of shell, probably spondylous and strombus, were found on board(Hemming 1970;Murra 1980: 140). Although the activity of this boat was described as trade (the word rescataris used in the text) by the Spanish observer Sámano-Xerez written in 1527-1528(Porras Barrenechea 1937: 21), it is highly likely that this boat, with its cargo of elite goods, was in fact carry ritual offerings from the Inka to some northern destination. The evidence for long distance exchange between Ecuador and Mesoamerica has been long been a topic of interest in New World archaeology(Coe 1960;Zeidler 1977).

Ecuadorian highlands

The strongest evidence for mercantilism and markets in the prehispanic Andean highlands comes from colonial Ecuador(Hartmann 1971;Salomon 1986). Hartmann argues that the Inka economy had a significant market component based the following evidence: (1) the Spanish saw gatherings that they identified as "markets" from the very earliest reports, although as they were coming from Mexico the Spanish used the Nahuatlword " tianguez"; (2) commodities were plentiful and varied, including both staple and luxury items; (3) both Quechua and Aymara had specialized terms for buying and selling; (4) market activity was not suppressed by the Inka authorities, only regulated to suit their interests(Hartmann 1971).

The existence of markets in prehispanic Ecuador is a particularly interesting question because the Quito area was conquered by the Inka only 30 years prior to the Spanish invasion and therefore the region had only recently been absorbed into the Inka Empire. Salomon(1986)examined the ethnohistoric evidence for precolonial and colonial markets in highland Ecuador and found that the contact period evidence provides insights into pre-Inka customs as well as the Inka response. The Quito valley is in a position to serve as a hub for the transfer of products from the Amazon lowlands, the Pacific coast, and the páramohighlands. In this sense, the Quito valley is in a similar geographical configuration, but on a smaller scale and a different ecological zone than the Lake Titicaca Basin. The strong dependence of early Spanish residents on the markets, and the founding of new markets by Spaniards, leads to some uncertainty as to the precolonial importance of markets. However, there is a variety of evidence for a pre-Inka merchant class in central Ecuador called mindaláesthat gathered in stationary markets and controlled trade in cotton, coca, and salt that they would bring from lower-lying regions(Salomon 1986: 203-204). Barter exchange between non-specialized traders occurred as well, typically of household surplus goods, and Salomon argues that both mindalamerchant organization and non-specialized barter were ancient developments in Ecuador. In contrast, Patterson(1987)argues that the merchantile organization was not a long-established system but rather a Late prehispanic period response to opportunities presented on the northern border of Tiwantinsuyu. Vertical archipelago organization is also found in Ecuador both in agricultural production and in targeted procurement communities such as stable colonies for salt production(Oberem 1981 [1976]: 79). However, Salomon shows that archipelagos were, in most cases, a late phenomenon that was introduced by the Inka. In addition, obsidian distributions in Ecuador can provide insights into Andean exchange in a context with functioning markets(Burger, et al. 1994).

As for trade specialization elsewhere in the Andes, LaLone(1982: 307)sees a latitudinal gradient from north to south where markets and freelance traders may have been more abundant in the northern periphery of the Inka empire, and subdued or non-existent in areas full under Inka control. A notable exception to this gradient are the sea traders from Chincha(Rostworowski 1977;Sandweiss 1992). The evidence is far less secure for the southern periphery of the Inka Empire, but the implication of the Ecuadorian data is that solving zonation problems through the vertical archipelago approach was promoted by the Inka in Ecuador following the Inka conquest, which perhaps calls into question the pervasiveness and pre-Inka antiquity of the vertical archipelago strategy in the south-central Andes as well.

Traveling Peddlers in the south-central Andes

In contemporary contexts, peddlers are found with frequency in areas that form boundaries areas between different commercial spheres of interaction and lacking in consistent distribution of goods. Browman (1990: 422) reviews ethnographic evidence for mobile peddlerswho perform bulk-forming and bulk-breaking services in the south-central Andean highlands. The peddlers will provide manufactured items to rural pastoral communities, though often at a substantial mark-up, and will trade for items like hides and wool in time for purchasing fairs in the regional centers. The puna between Lake Titicaca and the western slopes in Arequipa are particularly active with comerciantes ambulanteswho schedule their travel cycles to correspond with patron saint festivals, as well as distributing goods to communities without regular markets (Flores Ochoa 1977: 148 ;Flores Ochoa and Najar Vizcarra 1976) as well as traveling herbalists and related groups (Bastien 1987). In the small community of Cerrillos in southwestern Bolivia near the Argentinian border, Nielsen (2001: 166) reports that peddlers, referred to as cambalacheros, would pedal bicycles from the city of Oruro bringing clothes and metal pots to sell or to barter for hides.

The Collaguas of the Colca valley were frequently visited by itinerant peddlers from Puno, according to Casaverde (1977: 185). These vendors known as polveñosmaintain established compadrerelationshipswith Colca valley households in order to have reliable hosts and potential buyers in the valley. Although transactions frequently take place through barter and the host and other residents are not obliged to trade, the profit motive of the peddlers is understood. These examples illustrate some of the variety in forms of distribution that may have had some basis in the prehispanic economy.

Limitations of ethnohistory and ethnography

Ancient economy in the Andes has been most fruitfully studied by combining archaeological evidence with ethnohistoric and contemporary sources. General models of great importance to Andean studies such as vertical complementarity, the question of the commerce in the prehispanic economy, and a structure of dual organization in the Inka administration are examples of models emerging from ethnohistoric sources but with empirical support from archaeological research. Ethnohistorically based models also have their limitations in that they can unduly influence interpretation much in the way that the "tyranny of ethnography"(Wobst 1978)should not necessarily define the range of archaeological possibility and inference. Ethnographic sources are valuable for the evidence of pastoral patterns, the priorities of caravan drivers, and the articulation between mixed and specialized pastoral and agricultural practices. However, modern features including the presence of the cash economy, markets, truckers plying the highways, and various modern job opportunities impact the structure of exchange relationships and caravan transport(Browman 1990;Nielsen 2000).

Ethnographic studies of contemporary llama caravan drivers are focusing, by necessity, on relatively marginalized communities that are sufficiently conservative to continue to herd llamas despite a variety of often more lucrative alternatives (Lecoq 1988;Nielsen 2000). Scholars have noted, however, that caravan drivers enjoyed relatively high status and autonomy in the late prehispanic and early colonial period which contrasts strongly with the economically marginalized modern day caravanero(Murra 1965). Furthermore, herding has become relatively low status in many regions of the contemporary Andes because the economic focus has moved downslope since Spanish contact due to the growth of the coastal economy and the importation of various low altitude crops and livestock. In other words, the prominence of caravan drivers as central economic agents has been greatly diminished in recent centuries, and ethnographically documented interactions with agriculturalists is one circumstance in which this relative shift in power may result in distorted perceptions of prehispanic interaction patterns. The relatively high status accorded to truck drivers and other purveyors of goods and information in contemporary Andean villages was likely to have been ascribed, instead, to the relatively cosmopolitan drivers of llama caravans during prehispanic times.