Vertical complementarity

The contrasting ecological zonation found in low-latitude mountain regions worldwide has resulted in distinctive social configurations that appear to reduce risk, broaden the selection of products available in a given zone, and provide opportunities for strategic advancement by particular individuals or groups. These configurations have been investigated in two broad sets by Andeanists. First, there are a number of scholars who address vertical complementarity as a general process that is comparable with other mountain regions of the world. Second, there is a particular configuration known as "Vertical archipelagos" first described by John Murra (1972) that has been widely discussed in the Andean literature.

Verticality writ large

Vertical complementarity encompasses a variety of strategies for the problems posed by human use of resources at different scales, and by the broad natural diversity across relatively small distances in mountain environments (Aldenderfer 1993;Masuda, et al. 1985). These problems of articulation are addressed through mobility, through direct control of different zones by a single group, by mutualism between residents of different zones, and through a variety of exchange relationships. Vertical organization has been recorded among modern Quechua and Aymara communities (Brush 1976;Brush 1977;Flores Ochoa, et al. 1994;Harris 1982;Harris 1985;Platt 1980).

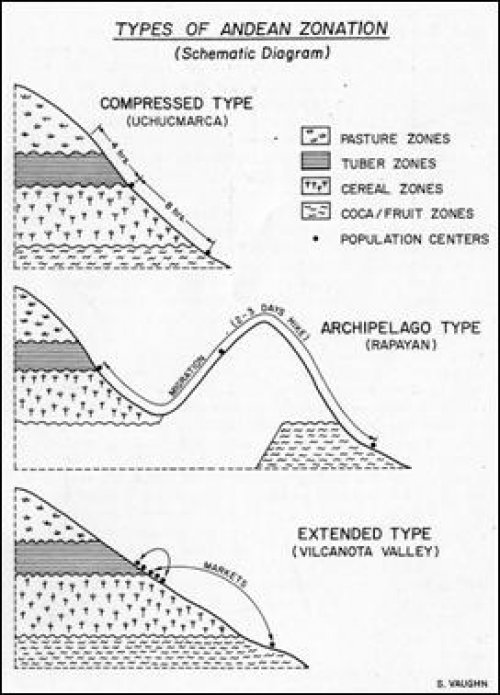

Figure 3-2. Contemporary types of Andean zonation (Brush 1977: 12 ).

Based on contemporary observations, Brush (1977: 11) describes three systems:

- the archipelago type, or vertical complementarity, as conceived by Murra;

- a compressed type, where a single village can access and control all resources without resorting to means of long distance control;

- the extended type that corresponds to horizontal complementarity.

On a more localized scale it is possible to see vertical control strategies within a particular valley in a mixed agropastoral strategy that has been called "compressed archipelago" (Figure 3-2). In the central part of the Colca valley on the western slope of the Andes in Arequipa, Peru, Guillet describes vertical household relations.

To what extent do households integrate both puna pastoralism and valley farming into their production and exchange strategies? First, most households residing in the puna tend to specialize in herding and do not have agricultural fields that they cultivate directly. Similarly, many village households neither belong to family surname groups with access to puna pastures nor count themselves among those who have gained control of communal pastures ( botaderos) on the slopes behind the village. Households that follow such specialized strategies must perforce use the exchange nexus to obtain complementary products (Guillet 1992: 133).

Additional evidence for micro and macro vertical complementarity is discussed in the context of the Colca valley (Casaverde Rojas 1977: 172;Málaga Medina 1977: 112-113;Pease G. Y 1977;Shea 1987: 71).

Vertical complementarity can viewed as an anthropological principle that describes the propensity for social groups in mountain environments, from foragers to state societies, to geographically broaden their social and economic base and reduce risk by exploiting a variety of environmental settings (Aldenderfer 1993;Guillet 1983;Salomon 1985). Salomon (1985: 520) presents complementarity strategies in prehispanic Ecuador as varying in two dimensions.

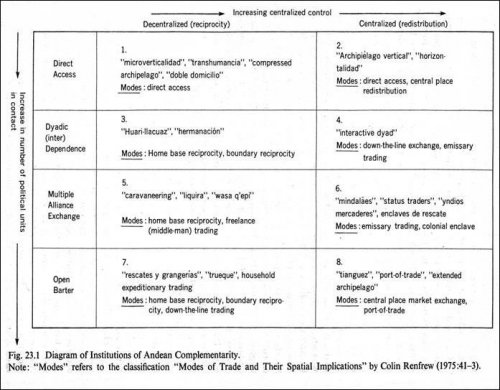

Figure 3-3. Diagram of institutions of Andean complementarity (from Salomon 1985: 520). Numbered modes reference the "Modes of Trade" in the figure from Renfrew (1975: 41-43 ) shown in the previous chapter as Figure 2-2.

One is between decentralized systems based on reciprocity, and the other is based on centralized systems of redistribution. There is an underlying neo-evolutionary correspondence implied in many of these models, as chiefdoms and states are believed to have been responsible for the network convergence perceived in redistributive systems, however it is important to observe that due to the variety in products, social relationships, and economic configurations, it is likely that a great many of the institutions presented in Figure 3-3 occurred simultaneously, and in general there is no direct correlation between confluence and evolutionary typologies. Another important dimension involves the number of political units participating in the interaction ranging from direct access, dyadic relations, exchange systems and open barter. The vertical complementarity literature in the Andes is valuable for considering prehispanic exchange relationships in that it has compelled a number of scholars to explore explicitly the relationship between ecological zonation, production, and social organization.

Vertical archipelagos

The work of John Murra on vertical complementarity has been among the most influential ethnohistoric studies in the Andes. The premise of the vertical archipelagos model is that the rapid altitudinal change along the flanks of the Andes produced a pattern where social groups residing in non-contiguous ecological strata formed distinct communities that developed around intensified production in these strata. Polities and ethnic communities sought to control a variety of these resource pockets following the Andean ideal of self-sufficiency.

Murra's (1972) seminal article distilled observations from ethnohistoric sources, in particular the visitacensus Garci Diez (1964 [1567]) of Chucuito in Puno, conducted only 35 years after the Spanish invasion. Murra showed that late prehispanic altiplano societies obtained direct access to products from a variety of ecological niches through this practice, and that the strategy was a guiding model of organization in some Andean polities (Salomon 1985). According to Murra (1985) the principal characteristics of the vertical archipelago model can be summarized as follows:

- Ethnic groups aimed to control numerous "floors" or ecological niches in order to exploit the resources that are found there and maintain self-sufficiency. As a consequence, powerful polities residing in the altiplano had considerable wealth in pastoral herds but also controlled land on both the western and eastern flanks of the Andes.

- The population was concentrated on the altiplano and those living in the peripheral 'islands' maintained continuous social and economic contact with the core region.

- The institutions of reciprocity and redistribution guaranteed that those living in 'islands' maintained the rights to products available in the center. These rights were defined through kinship ties that were ceremonially reaffirmed in the center.

- A single 'island' could be shared by different ethnic groups, though the coexistence could be tense.

- The relationships and functions of these colonies changed through time and may have become more exploitative. They are perhaps an antecedent to the mitimaqstrategy of the Inka empire.

While a chiefdom level of organization and centralized power is a principal characteristic of the Late Intermediate polities that practiced vertical complementarity in the period examined by Murra, the concept was been explored and expanded by archaeologists in the subsequent decades. In Murra's original description, verticality referred explicitly to direct control of a diverse resource base without engaging in trade with other ethnic groups, thereby preserving what Murra (1972) has described as the ancient Andean ideal of economic self-sufficiency that permeated Andean society and ideology far beyond his Lupaca case study. Stanish argues that Murra was explicit about excluding exchange processes, in part, because he perceived "a structural linkage between exchange and markets" (1992: 15). As prehispanic market mechanisms were absent in the south-central it was believed that barter and exchange were also of minimal importance and other means of articulation, such as direct control, were emphasized. Murra, however, later modified the definition to include specialized exchange centers, a change which Browman (1989: 324) argues confuses the issue because it subsumes a variety of processes into a single model.

On a theoretical level a further limitation of the original 'verticality archipelago' model lies in its adaptationalist orientation (Earle 2001).Adaptationist models of exchange and regional control have their basis in Service's (1962) proposal that these arrangements arise from environmental diversity, and then chiefs emerge to administer and redistribute goods produced regularly by their retainers.As observed by Van Buren (1996: 346), the archaeological origins and perpetuation of the archipelago pattern was founded on the assumption that groups benefit, as a whole, from the control of multiple tiers and the ecological resources that are produced in those archipelagos. As mentioned above in the discussion of administered trade, colonial documents emphasize the independence of commoners and the ability of subjects to practice subsistence barter, a pattern that leads authors to suggest that the vertical archipelagos pattern may have had more of a political basis than a foundation in ecological and subsistence practices. The ultimate roots of such a system may lie instead in the capacity of the rulers of such groups to organize larger scale trade and convert the value differential between products in the different ecological zones into political prestige through feasting and ceremony (Stanish 2003: 69-70).