3.5.1.Archaic Foragers in the South-Central Andes

To date, relatively few Archaic archaeological sites have been excavated in the area of the south-central Andean highlands, and therefore the regional knowledge of this important time period is limited. A brief overview of each period will be provided here, with an emphasis on archaeological sites containing Chivay type obsidian, in order to contextualize the regional relationships and interactions that were occurring during these preceramic periods. This review will focus on the western slope of the Andes and the Lake Titicaca Basin, the region where Chivay type obsidian abounds. Much of the Archaic Foragers obsidian in the literature that has been sourced was derived from undated, surface contexts from sites that are assumed to date to the Archaic based on projectile point styles or other inference by archaeologists. Klink and Aldenderfer's (2005) projectile point typology permits the classification of site occupations by time period with greater certainty during the Archaic when projectile point styles change with regularity. In some cases, the projectile point typology can be used to assign a date range to temporally diagnostic obsidian projectile points that have been directly analyzed for chemical provenience.

In Burger et al.'s (2000: 275-288) review, procurement and exchange during the preceramic is evaluated through chemical provenancing data from 87 obsidian samples, 70 of which are from the Chivay source. Unfortunately, of the thirteen sites where the samples were collected in the south-central highlands, only three sites (Chamaqta, Asana, and Sumbay) contain excavated contexts placing the samples in preceramic levels. The other samples are assigned to the preceramic group through inference from projectile points, or because they are from a-ceramic sites. The difficulty in this arises from the fact that obsidian was used with much greater frequency in the beginning of the pastoralist periods, as was mentioned above in the case of the Ilave valley (Section 3.4.4 ).

Obsidian materials from both the Chivay and Alca sources were transported relatively long distances from the Early Archaic onward, indicating that material from these obsidian sources has properties that were prized at a relatively early date. Sites such as Asana and Qillqatani, both over 200 linear km from the Chivay source, contain non-local obsidian through much of the preceramic sequence despite the immediate availability of high quality cherts, as well as the lower-quality Aconcahua obsidian, in the local area. This evidence underscores the nature of obsidian provisioning in the Archaic Period. As compared with later pastoralist use of obsidian, Archaic foragers were relatively selective in their use of raw materials. This may reflect the priority placed on dependable hunting technology as compared with the shearing and butchering needs of pastoralists, or the different social and symbolic priorities attached to obsidian by hunters versus herders.

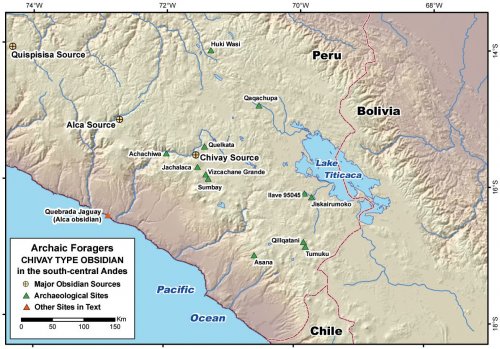

Figure 3-11. Chivay type obsidian distributions during the "Archaic Foragers" time(circa 10,000 - 3,300 BCE).

Early Archaic (circa 10,000 - 7,000 BCE)

Evidence from the Early Archaic in the south-central Andes is slim, but it is accumulating gradually. The available data suggest that during this time period human groups went from initial exploration of the highlands to more stable, year around occupation of the sierra and puna. The best evidence from the highlands comes from a handful of stratified sites in the region with Early Archaic components, as well as distributional evidence from archaeological survey work(Aldenderfer 1997;1998;1999;2003;Craig 2005: 452-484;Klink 2005;Nuñez, et al. 2002;Santoro and Núñez 1987;).

A regional study of projectile points from excavated contexts by Klink and Aldenderfer(2005: 31, 53)noted that projectile point styles diagnostic to the Early Archaic (Series 1 and Types 4a, 4b) and the Early-Middle Archaic transition (Type 2a) have a broad geographical distribution. These types are found throughout a region that includes the littoral, western sierra, and puna areas of extreme northern Chile and southern Peru, and as far north as Pachamachay cave in the Junin puna(Rick 1980). Given the low population densities of that time period, this wide regional stylistic distribution suggests that a high degree of mobility was being practiced in the Early Archaic and first part of the Middle Archaic. Further to the north, in contrast, raw material types in the Junin puna of central Peru suggest to Rick(1980)that very low forager mobility was occurring throughout the early preceramic period. Early Archaic obsidian distribution data largely confirm with the model of high mobility and show that humans found good sources of lithic raw material in the sierra early, and then transported the material or exchanged it widely from a relatively early date.

Current paleoclimate evidence indicates that glaciers advanced during the late glacial between 11,280 and 10,99014C yr bp, and then, despite cool temperatures, the glaciers receded rapidly, perhaps as a result of reduced precipitation(Rodbell and Seltzer 2000). Glaciers were in approximately modern positions in southern Peru by 10,90014C yr bp (circa 11,000 cal BCE). The Early Archaic Period, with reference to diagnostic projectile point styles(Klink and Aldenderfer 2005), begins at circa 9000 cal BCE During the Early Holocene and the first part of the Early Archaic conditions were wetter and cooler than modern conditions. Subsequently, during the latter part of the Early Archaic, the climate began an episode of long-term aridity that lasted through the Late Archaic(Abbott, et al. 1997;Argollo and Mourguiart 2000: 43;Baied and Wheeler 1993;Paduano, et al. 2003: 272). Opportunities in the highlands for human foraging groups were created by a number of new ecological niches for plants and animals that opened up during the Early Holocene. These niches represented a resource pull for mobile foragers that countered the increased difficulty of subsistence in the hypoxic, high altitude environment faced by the non-adapted early settlers in the highlands(Aldenderfer 1999). A review of the evidence for forest cover on the altiplano during the Archaic, with deforestation occurring as a result of pastoral intensification, is provided by Gade(1999: 42-74).

During the Late Pleistocene lacustrine period, paleo-Lake Titicaca (Lake Tauca) was much larger but only a few meters higher than is modern Lake Titicaca (Clapperton 1993: 498-501). Radiocarbon dates on shells show that Lake Tauca was probably still present as late as 10,08014C yr bp (or 9900 cal BCE). Sediment cores from Lake Titicaca indicate that there was an increase in sub-puna vegetation and fire from vegetation prior to 9000 BP (Paduano, et al. 2003: 272). Evidence from paleoclimate records and fluvial geomorphology point to a time of increased aridity and salinity in Lake Titicaca, with short, episodic moist spells beginning around 8000 cal BCE and continuing through the Middle Archaic and Late Archaic Periods (Rigsby, et al. 2003;Wirrmann, et al. 1992). The climatic data for this time suggest that with deglaciation in the Early Holocene a resource niche opened up that exerted a pull on plant and animal species towards the high altitude regions, and that early human groups responded to these opportunities by colonizing the high Andes.

Chivay obsidian in the Early Archaic

Evidence of human use of the Chivay Source beginning in the Early Archaic Period comes from survey work adjacent to the source and from excavations at the site of Asana, 200 km away in Moquegua. As will be discussed in Chapter 7, during the course of survey work in the area of the Chivay source in 2003 the Upper Colca team collected several dozen Early Archaic type projectile points, the majority of them made from obsidian. Evidence for the regional consumption of Chivay obsidian begins with the site ofXAsanaXthat were described earlier in SectionX3.4.1XandXTable 3-4X. Aldenderfer(1998: 157, 163;2000: 383-384)encountered small quantities of obsidian in two levels belonging to the Asana II/Khituña Phase, placing them in the Early Archaic Period. In level PXXIX just one obsidian flake from Chivay was identified in an assemblage consisting of 1,152 lithic artifacts weighing 746 g. This level could not be dated directly, but it is assessed at 9400 uncal bp as it lies stratigraphically above a14C sample from level XXXIII dating to 9820±15014C yr bp (Beta-40063; 10,000-8700 BCE).

Obsidian from Chivay appeared in greater quantity in level PXXIV where eleven flakes of Chivay obsidian made up 0.36% of the lithic assemblage by count. These flakes were all small tertariary flakes, chunks, and shatter, suggesting to Aldenderfer(1998: 163)that a bifacial core of Chivay material was reduced on site. A14C sample from level PXXIV dated to 8720±120 bp (Beta-35599; 8250-7550 BCE). The Khituña phase has been interpreted by Aldenderfer(1998: 172-173)as representing a residential base in the high sierra and the beginnings of permanent settlement above 2500m in elevation. This interpretation is based on the presence of high sierra and puna lithic raw materials, but no coastal materials.

In surface contexts in the Ilave valley, surveys directed by Aldenderfer(1997)located three obsidian projectile points in forms that are possibly diagnostic to the Early and Early-Middle Archaic transitional period (types 1A, 3A, 3B). These three points were analyzed using a portable XRF unit in 2005 and all three were found to be of the Chivay type(Craig and Aldenderfer In Press).

Alca obsidian at Quebrada Jaguay

The earliest obsidian identified in the south-central Andes comes from one of the oldest confirmed sites in South America, the Paleo-Indian site of Quebrada Jaguay 280 near the coast north of Camaná, Arequipa. Sandweiss et al.(1998)report that Alca type obsidian was the dominant lithic material at the site in the Terminal Pleistocene and Early Holocene phases that were identified. Twenty-six Alca type obsidian flakes came from the older occupation that occurred during the Terminal Pleistocene and the context is dated by twelve14C dates on charcoal falling between 11,105±260 bp (BGS-1942; 11,700-10,400 BCE) and 9850±170 bp (BGS-1956; 10,100-8700 BCE). A later occupation contained one flake of Alca obsidian and it belonged to the Early Holocene II phase dated by four14C samples falling between 8053±115 (BGS-1944; 7350-6650 BCE) and 7500±130 (BGS-1700; 6600-6050 BCE). Three other obsidian flakes from the Alca source were collected but they could not be assigned to a temporal context.

Sandweiss et al. observe that the Chivay source is "less than 20 km further; the absence of Chivay obsidian at QJ-280 may indicate that this source was covered by glacial readvance during the Younger Dryas (circa 11,000 to 10,00014C yr B.P.)"(Sandweiss, et al. 1998: 1832). The Maymeja volcanic depression of the Chivay obsidian source indeed shows notable evidence of recent glaciation, but obsidian matching the "Chivay Type" is also found in smaller nodules on adjacent slopes outside the Maymeja zone as well as in the streambed below Maymeja having eroded through alluvial erosion (see Section4.5.1for maps and a discussion of the Chivay obsidian source geography). Procurement of obsidian from Chivay did not necessarily require entering the Maymeja area, however better source material can be obtained from the within the area.

Regional scale GIS analyses show Quebrada Jaguay to be 154 linear km from the Alca source, or 35.7 hours by the hiking function. In contrast, the trip to Quebrada Jaguay from the Chivay source is 170 linear km and 41.5 hours by the hiking function. Despite this relatively difference in distance, no Chivay obsidian was found at Quebrada Jaguay. It is worth noting that, despite this early find of Alca obsidian on coast, both the Alca and the Chivayobsidian types were predominantly found at high altitude throughout prehistory based on current evidence from obsidian sourcing studies. In the bigger picture, the coastal Quebrada Jaguay paleoindian finds are anomalous for Alca distributions. The next lowest altitude context for Alca to date is at the site of Omo in Moquegua, a Tiwanaku colony site at 1250 masl dating to the Middle Horizon.

Recent work by Kurt Rademaker and colleagues at the Alca source has shown that bedrock outcrops of obsidian are found as high as 4800 masl, and there are large pieces found at 3,800 masl that appear to have been transported downslope by glacial action and colluviation (K. Rademaker 2005, pers. comm.). Deposits of Alca obsidian at much lower elevations have been reported that are probably the result of pyroclastic flows(Burger, et al. 1998;Jennings and Glascock 2002). These deposits found close to the floor of the Cotahuasi valley at 2500 masl were probably available throughout the Younger Dryas and perhaps further sub-sourcing of Alca obsidian will better answer the question of which Alca deposits were being consumed during the Terminal Pleistocene by the occupants of Quebrada Jaguay.

Quispisisa Obsidian in the Early Archaic

Another early use of obsidian in the Andes is the evidence of Quispisisa obsidian in levels dated to ~9000 uncalBP or 8500-7750 cal BCE (Burger and Asaro 1977;Burger and Asaro 1978;Burger and Glascock 2000;MacNeish, et al. 1980) from Jaywamachay a.k.a. "Pepper cave" (Ac335) located at 3300 masl in Ayacucho in the central Peruvian highlands. As was recently explained by Burger and Glascock (2000;2002), for nearly three decades the Quispisisa obsidian source was mistakenly believed to have been located in the Department of Huancavelica, but in the late 1990s the true Quispisisa source was finally discovered in the Department of Ayacucho. Jaywamachay is the closest of the sites excavated by MacNeish's team to the newly located Quispisisa source. It is 81.3 linear km or 22.0 hours walking calculated using the hiking function, while the bulk of the sites excavated by MacNeish were in the Ayacucho valley approximately 120 km from the relocated Quispisisa source. The Puzolana (Ayacucho) obsidian source is located close to the Ayacucho valley and high-quality, knappable obsidian is available at this source, but the maximum size for these nodules is 3-4 cm, significantly limiting the potential artifact size for pieces made from this source (Burger and Glascock 2001). It is interesting to note that, in several cases in the south-central Andes, the Archaic Period foragers seem to have ignored small sized or low-quality obsidian sources that later pastoralists ended up exploiting. The Aconcahua source near Mazo Cruz, Puno, previously described, was not used at the adjacent Qillqatani rock shelter until the Middle Formative (Frye, et al. 1998), and it was not used at Asana until the Terminal Archaic (Aldenderfer 2000: 383-384).

Burger and Asaro(1977: 22;1978: 64-65 )chemically analyzed a projectile point of Quispisisa obsidian found at La Cumbre in the Moche Valley that was reportedly from a context dated to 8585±280 bp or 8500-6800 cal BCE(Ossa and Moseley 1971). The investigator, Paul Ossa, now doubts the Early Archaic context and instead believes the point may be Middle Horizon in date (Richard Burger, 11 March 2006, personal communication), but it is still a noteworthy case of long distance transport within the Wari Empire, and it perhaps involved the use of coastal maritime transport. Using the relocated Quispisisa source in the Department of Ayacucho the linear distance is 846.7 km and by the hiking function the distance is calculated as 199.8 hours, primarily confined to the coast.

Discussion

Regional relationships indicated by both stylistic criteria and obsidian distributions point to high mobility during the Early Archaic Period. Recent evidence of projectile point similarities from northern Chile suggest that mobility was high along the Pacific littoral, and between the sierra and puna during the Terminal Pleistocene and Early Holocene around 25° S latitude(Grosjean, et al. 2005;Nuñez, et al. 2002). During the Early Holocene, foraging groups resided around high altitude paleo-lakes on the altiplano of northern Chile between 20° S and 25° S latitude that persisted longer than did the paleo-lakes at the latitude of Lake Titicaca. These lakes subsequently dried up during the Middle Archaic Period and occupations declined until the end of the Late Archaic Period but this distributions point to the mobility and early high altitude occupation of the adjacent puna of Atacama.

On the whole, obsidian proveniencing and analysis has shed light on human activities during the Paleoindian period and Early Archaic at a regional scale. Chemical analysis techniques, non-destructive XRF analysis in particular, are becoming more pervasive because the methods are being refined and the equipment is becoming more portable. Further field research will provide a greater understanding of this time period, but evidence will also likely to emerge from existing collections as obsidian projectile points diagnostic to the Early Archaic are systematically provenienced.

Middle Archaic (7000 - 5000 BCE)

The Middle Archaic Period, as with the preceding period, is still poorly understood in the region as very few highland sites containing stratified deposits have been studied from this period. In the Lake Titicaca Basin paleo-climatic evidence points to significant aridity, a lake level approximately 15m below the current stand, and high salinity in Lake Titicaca that is comparable to that of modern day Lake Poopó(Abbott, et al. 1997;Wirrmann and Mourguiart 1995). Human occupation during the Middle Archaic in the Lake Titicaca Basin was notably higher than in the preceding period, but research shows that settlement continued to occur in the upper reaches of the tributary rivers and not adjacent to the shores of the saline Lake Titicaca(Aldenderfer 1997;Klink 2005).

Obsidian distributions during the Middle Archaic

At the site of Asana on the western slope of the Andes, Aldenderfer(1998: 223)observed architectural features that suggest that a longer residential occupation of the site by entire coresidential groups was occurring in the latter part of the Middle Archaic Muruq'uta phase.One flake of obsidian from the Chivay source was found in the upper levels of theMuruq'uta phase (XTable 3-4X).This occupation dates to the Middle Archaic -Late Archaic transition as the flake was stratigraphically above a14Csample that dated to 6040 ± 90 bp (Beta-24634; 5210-4720 BCE).

At the rock shelter of Sumbay SU-3 obsidian was recovered from excavation levels that date to as far back as the transition between the Middle and Late Archaic (SectionX3.4.3X).

Discussion

Relatively little is known about the Middle Archaic in the south-central Andean highlands. Elsewhere in the south-central Andes, archaeologists have noted an absence of settlement during the mid-Holocene timeframe corresponding to the Middle and Late Archaic Periods. In the dry and salt puna areas of northern Chile, and along the south coast of Peru, a significant decline or absence of mid-Holocene sites has led investigators to refer to this period as the silencio arqueológico(Nuñez, et al. 2002;Núñez and Santoro 1988;Sandweiss 2003;Sandweiss, et al. 1998). This designation apparently does not apply to the Titicaca Basin or to the sierra areas of the Osmore drainage where no Middle Archaic occupation hiatus has been observed.

With gradual population increases and adaptation to the puna, social networks extending across the altiplano and connecting communities and their resources residing in lower elevations with puna dwellers, were probably beginning to take form. Exchange of resources, including obsidian, between neighboring groups may have been in the context of both maintaining access to resources and risk reduction. From a subsistence perspective, Spielmann (1986: 281) describes these as buffering, a means of alleviating period food shortages by physically accessing them directly in neighboring areas, and mutualism,where complementary foods that are procured or produced are exchanged on a regular basis. Another likely context for obsidian distribution during the Archaic Period is at periodic aggregations. Seasonal aggregations have been well-documented among foragers living in low population densities, where gatherings are the occasion for trade, consumption of surplus food, encountering mates, and the maintenance of social ties and ceremonial obligations (Birdsell 1970: 120;Steward 1938). If analogous gatherings occurred among early foragers in the south-central Andes it have would created an excellent context for the distribution of raw materials, particularly a highly visible material like obsidian that was irregularly available in the landscape.

Late Archaic (5000 - 3300 BCE)

The Late Archaic in the south-central Andes signals the beginning of economic changes in the lead-up to food production, and furthermore the first signs of incipient social and political differentiation are evident in a few archaeological contexts. Some of the obsidian samples reported by Burger et al(2000: 275-288)with possible Late Archaic affiliations are from surface contexts at multicomponent sites and it is therefore difficult to confidently assign these samples to any particular period of the Archaic.

Chivay obsidian during the Late Archaic

Evidence of Late Archaic obsidian use comes from excavations at the previously discussed sites of Asana, Qillqatani, and Sumbay. Several obsidian samples in the Burger et al. (2000) study were of portions of diagnostic projectile points that resemble types in Klink and Aldenderfer's (2005) point chronology. From illustrations and text(Burger, et al. 2000: 279, 281)the Qaqachupa sample appears to belong to the Late Archaic. Burger et al. describe this point as resembling a Type 7 point from Toquepala in Ravines'(1973)classification, and Klink and Aldenderfer(2005: 44)mention that their Type 4D point strongly resembles the Toquepala Type 7, making it diagnostic to the Late Archaic.

Asana

In excavated data from Asana, in Moquegua, one sample of Chivay obsidian was found in a Muruq'uta phase occupation in Level XIV-West lying above a palimpsest dated to 6040±90 (Beta-24634; 5210-4766 BCE) (Aldenderfer 1998: 269), as shown above in SectionX3.4.1X. This level lies on the Middle Archaic / Late Archaic transition. Interestingly, Chivay obsidian disappears at Asana subsequent to this time period. Furthermore, evidence of lower raw material diversity in the Late Archaic lithic assemblage point to greater geographical circumscription.

Qillqatani

Chivay obsidian at Qillqatani is first found in the Late Archaic level WXXX dated to 5620±120 (Beta-43927; 4800-4200 BCE). The Chivay material is the second oldest obsidian fragment identified from Qillqatani (SectionX3.4.2X), the oldest obsidian is from an as-yet unknown source. Notably, the assemblages from the Qillqatani excavations do not begin to contain obsidian from the Chivay source until considerably later date than did the excavations from Asana.XFigure 3-7Xreveals that both obsidian tools and debris increase as a percentage of the assemblage in the Late Archaic. The counts of obsidian, however, are still relatively low.

Qillqatani is slightly further away than Asana than from the Chivay source, and it is at a higher altitude and further to the east. It has been suggested that perhaps the obsidian was transported via a coastal route at this early date (Frye, et al. 1998). As mentioned, Alca obsidian was also found on the coast in the Terminal Pleistocene levels although, like Chivay, Alca obsidian distributions conform over the long term to a highlands orientation. As no Chivay obsidian as ever been found below the 1250 masl (at Omo), and all Archaic Period Chivay obsidian is found above 3000 masl, the littoral route between Chivay and Asana seems improbable.

IlaveValley

Craig and Aldenderfer(In Press)report that two obsidian projectile points from the Ilave valley in a type 3f form, diagnostic to the Late - Terminal Archaic were analyzed in 2005 with a portable XRF unit and were found to be of the Chivay type.

Sumbay

At Sumbay SU-3,three obsidian samples were analyzed from excavated contexts and all three turned out to be of the Chivay type(Burger, et al. 1998: 209;Burger, et al. 2000: 278), as shown in SectionX3.4.3X. Two14C dates were run and returned dates from the early part of the Late Archaic(Ravines 1982: 180-181). One sample was from stratum 3 and it was dated to 6160±120 (BONN-1558; 5400-4750 BCE). Another sample was from above it in stratum 2 and it dated to 5350±90 (BONN-1559; 4350-3980 BCE). One of the three obsidian samples came from Stratum 4 of unit 5, while the other two samples came from higher levels. The Stratum 4 sample probably dates to the Middle Archaic.

Discussion

Obsidian from securely dated Late Archaic contexts show something of a reduction in regional distribution and a greater focus on locally available lithic material, suggesting a reduction in mobility or exchange in the Late Archaic. Similarly, projectile point styles became increasingly more limited in spatial distribution, with greater local variability during the Late Archaic implying reduced mobility(Klink and Aldenderfer 2005: 53). This is consistent with Aldenderfer's(1998: 260-261)observations about reduced mobility during the Late Archaic Qhuna Phase occupation at Asana when the occupants ceased to use non-local lithic raw materials. During this phase, Aldenderfer also describes increasingly formalized use of space at Asana, evidence of a ceremonial complex, and greater investment in seed grinding. In short, during this time a circumscribed population with reduced mobility was probably living in higher densities and exhibiting signs of ceremonial activity that are consistent with the scalar stress model for the emergence of leadership(Johnson 1982).

It is also worth considering the impact that scarcity may have on valuation. The lack of discarded obsidian signifies that it was not being knapped or resharpened and it was probably not abundant, but that does not mean that obsidian was not known in the larger consumption zone during this period. In the subsequent time period, the Terminal Archaic, obsidian becomes abundant on a regional scale at the same time as a host of other social and economic changes were occurring. This period, and the previously discussed Middle Archaic, correspond with what was referred to as the silencio arqueologico(Núñez and Santoro 1988)due to a dearth of archaeological data observed by investigators working in Northern Chile. The reduced evidence of circulation of obsidian from Chivay appears to correlate with a reduction in archaeological evidence regionally.

Thereis strong representation of Chivay obsidian in Arequipa at Sumbay, and it is likely that Late Archaic projectile point forms are found in the North Titicaca Basin as reported by Burger et al. (2000). However, at Asana there is little obsidian from the Colca. Possibly these reduced distributions of obsidian reflect the reduced mobility and more complex architectural investment in Late Archaic contexts at Asana(Aldenderfer 1998), and prior to the development of extensive, long distance exchange that were potentially initiated by early caravan networks during the Terminal Archaic.These conclusions, however, on not based on particularly robust data, as the sample of sites for this time period is relatively small.

Discussion and review of the Archaic Foragers period

The transport of obsidian from both the Chivay and Alca sources fluctuated during the Archaic Foragers period, and the distribution remained confined to the sierra and altiplano areas of the south-central Andes. The small and irregular quantities of obsidian consumed throughout the region could have been procured and transported by mobile foragers, or conveyed through down-the-line exchange networks. Conceivably exchange could have taken place a seasonal gatherings as well, based on analogy from other foraging groups worldwide, although there is no direct empirical support for such gatherings in the south-central Andean Archaic. At Asana, the most well-stratified highland Archaic site investigated to date, evidence of non-local obsidian was intermittent and consisted of very small quantities of material in a pattern that is perhaps exemplary of the discontinuous nature of regional exchange during this time.

Obsidian from the Quispisisa source (340 linear km to the north-west of the Chivay source), was likewise used primarily in highland contexts during the Archaic Foragers period, particularly in rock shelters excavated by MacNeish and colleagues in the central highlands. While Quispisisa material was circulated at a number of preceramic coastal sites(Burger and Asaro 1978), current evidence suggests that those contexts post-date 3300 cal BCE (i.e., cotton preceramic) and are therefore Terminal Archaic in the terms used here. It appears that while Quispisisa material was used widely on the coasts subsequent to the Archaic Foragers period, material from Chivay and Alca were virtually always confined in the highlands with the exception of the earliest obsidian evidence of all: Alca at Quebrada Jaguay. In the Archaic Foragers period, as in later periods, the evidence from obsidian is contrary to the widely-discussed Andean vertical complementarity models, because obsidian distributions suggest that the movement of people or products between ecologically complementary zones was not widespread.