3.5.2.Early Agropastoralist obsidian distributions

The "Early Agropastoralists" period (3,300 BCE - A.D. 400) begins with what appears to have been a shift to a chiefly pastoral lifeway, greater regional interaction, and a more intensive production and circulation of obsidian from the Chivay source area in the Terminal Archaic. In this discussion, the Early Agropastoralists period continues through the Late Formative and subsequently beginning AD400, with the ascendancy of Tiwanaku, the "Late Prehispanic" time block begins. The changes during the Terminal Archaic that mark the beginning of the Early Agropastoralist time include the growing importance of food production, the expanded production and circulation of obsidian, and socio-political differentiation that began to appear in the Terminal Archaic, phenomena of greater interest to this research than the presence or absence of pottery.

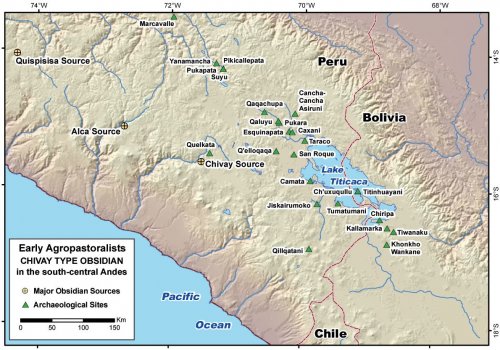

Figure 3-12. Chivay type obsidian distributions during the "Early Agropastoralists" time (3,300 BCE - AD 400).Why an "Early Agropastoralists" time block?

In lieu of the traditional preceramic / ceramic divide in archaeology, the "Early Agropastoralist" time block was defined for this project because, in many ways, the conditions during the final millennium of the Archaic had more in common with events in the Formative than with the preceding Archaic Periods. Differentiating sites as "Early Agropastoralist" beginning in the Terminal Archaic requires that one delimits a firm boundary on a process that was millennia in the making. Considering the Terminal Archaic as the beginnings of agropastoralism, and thereby linking it to the attendant settlement distribution that includes series 5 projectile points, connects cultural and economic evidence from throughout the region with a generalized estimate of when food production took hold in terms of scheduling, mobility, and prioritizing the needs of agricultural planting and herding. As mentioned, the term "Early Pastoral" is not meant to imply that no food production occurred before this date and hunting and gathering did not persist after this date. Indeed the current evidence suggests that camelids were first domesticated sometime during the Middle or Late Archaic, probably after 5000 BCE (Browman 1989;Kadwell, et al. 2001;Wheeler 1983;Wing 1986). The "Early Agropastoralist" period refers to a period after 3300 BCE that features a predominantly food producing economy in the highlands including intensive pastoralism, as well as seed-plant and tuber cultivation. These changes in food production may have been linked to the accumulating evidence of increased rainfall and shortening of the dry season beginning circa 2500 cal BCE (Baker, et al. 2001;Marchant and Hooghiemstra 2004;Mourguiart 2000). These changes in economy are joined by evidence of increased sedentism, widening stylistic distributions pointing to long distance cultural integration, and the beginnings of social differentiation apparent in architecture and grave goods. The circulation of obsidian was linked to these phenomena because increased regional interaction was perhaps articulated through camelid caravans, although the presence of caravans in the Terminal Archaic is being explored, not assumed, in this study.

In the Titicaca Basin, the changes incurred between the Terminal Archaic and the Late Formative are monumental. However, from the perspective of the Chivay source the intensification revealed archaeologically, both at the source and in the consumption zone, is notable beginning in the Terminal Archaic, and the intensification does not change notably throughout the Formative Period. Defining the ending of the "Early Agropastoralist" period as the end of the Late Formative is similarly problematic. By the Late Formative, the economic influence of Pukara and other regional centers probably impacted the peoples of the Upper Colca, but direct evidence returning from Pukara, only 140 km away, is scarce in the Colca. In contrast, during the Tiwanaku times, regional states with socio-economic impacts over hundreds of kilometers dominated both the circulation of goods like obsidian, and regional settlement organization.

Terminal Archaic (3300 - 2000 BCE)

The Terminal Archaic ushers in a suite of social and economic changes in the south-central Andes and, consistent with these developments, obsidian begins to circulate in significantly greater quantities during this period. Obsidian is increasingly used for projectile points during the Terminal Archaic, a trend that continues into the Formative Period (Burger, et al. 2000: 294).

Regional patterns in Terminal Archaic sites are somewhat difficult to assess from surface finds because the Terminal Archaic is lacking in exclusive diagnostic artifacts in both the lithic or ceramic artifact classes. As is shown inXFigure 3-10X, the most common projectile point styles that belong to the Terminal Archaic, such as Types 5B and 5D, also persist through the ceramic periods, leaving only type 5A and part of type 4F as diagnostic to exclusively the Terminal Archaic (Klink and Aldenderfer 2005: 48). Furthermore, by definition, the Terminal Archaic is a preceramic period, which precludes a ceramic means of assigning chronology. From site organization characteristics, a site might be considered to be a Terminal Archaic site if it has pastoralist attributes but it is aceramic and has series 5 projectile point types represented that belong, at least partially, to the Terminal Archaic.

The beginnings of the Andean agropastoral strategy are apparent during this period at sites like Asana where seasonal residential movement occurred between the high sierra and the puna (Aldenderfer 1998: 261-275;Kuznar 1995). Another attribute of the Terminal Archaic at Asana is a disappearance of ceremonial features. Evidence for a shift from hunting to pastoralism comes primarily from evidence of corrals (Aldenderfer 1998), from changes in the ratio of deer to camelid remains, and from the ratio of camelid neonate to adult remains. At sites where the process has been observed, the transition to full pastoralism at various sites in the Andes is usually perceived as a gradual process dating to sometime between 3300 to 1500 BCE At Qillqatani, however, the transition was relatively abrupt and it occurred in level WXXIV that dates to approximately 2210-1880 BCE (XTable 3-1X).

Chivay obsidian during the Terminal Archaic

While the number of excavated Terminal Archaic sites is relatively small, general processes are apparent from recent work at several sites in the south-central Andean highlands.

At Ch'uxuqullu on the Island of the Sun, Stanish et al.(2002)report three obsidian samples from the Chivay source in Preceramic levels. Eight obsidian flakes were found in aceramic levels and were described as being from a middle stage of manufacture, and three of these were sourced with NAA. Two samples came from levels with a14C date of 3780±100bp (Teledyne-I-18, 314; 2500-1900 BCE) and a third Chivay obsidian sample comes from an aceramic level that immediately predates the first ceramics level which occurred at 3110±45bp (AMS-NSF; 1460-1260 BCE). Citing paleoclimate data, the authors observe that boat travel was required to access the Island of the Sun at this time.

The Ilave Valley and Jiskairumoko

Terminal Archaic projectile points in the Ilave valley demonstrate the dramatic shift in the frequency and use of obsidian that occurred in this time period (SectionX3.4.4X). XRF analysis of 68 obsidian artifacts excavated from Jiskairumoko show that the Chivay source was used with particular intensity in this period. The XRF study found that 97% of obsidian bifaces from Terminal Archaic and Early Formative levels at Jiskairumoko were from the Chivay source, however published obsidian studies from all time periods show that typically 90% of all obsidian analyzed from Titicaca Basin sites are from the Chivay source (XTable 3-3X).

Qillqatani

The percentages of obsidian tools and debris remain generally similar to those in the Late Archaic level except that the counts are much higher (XFigure 3-7X). By count, obsidian tools are doubled, and obsidian debris is 4.3 times greater, and all the obsidian has visual characteristics of the Chivay type (Aldenderfer 1999).

Based on the density of obsidian, the relationship with the Chivay source area 221 km away seems to be well-established by this time, and it is a relationship that becomes even more well-developed in the Early Formative. Six samples of obsidian were analyzed at the MURR facility from Terminal Archaic contexts that are associated with a radiocarbon date of 3660±120 (Beta-43926; 2210-1880 BCE). All six obsidian samples were from the Chivay source.

Asana

At the site of Asana, obsidian reappears at the end of the Terminal Archaic during the Awati Phase dated to3640±80 (Beta-23364; 2300-1750 BCE)where it makes up 0.4% of lithic materials, but this obsidian was not from the Chivay source. It was judged from distinctive visual characteristics to have come from the Aconcagua obsidian source only 84 km to the east of Asana, near the town of Mazo Cruz(Aldenderfer 2000). Aconcahua type obsidian has characteristics that are less desirable for knapping due to fractures and perlitic veins that cross cut the material (see Appendix B.1), and while it was possible to derive sharp flakes for shearing and butchering functions, the material was probably not used for projectile point production(Frye, et al. 1998).

The shift to Aconcahua obsidian in the Awati phase at Asana is particularly puzzling given the evidence for Chivay obsidian circulation at this time period. It is precisely at the end of the Terminal Archaic that a dramatic spike in the use of Chivay obsidian at Qillqatani (SeeXTable 3-5XandXFigure 3-7X) took place. One may ask: Why is it that when the occupants of Qillqatani are importing Chivay obsidian in unprecedented quantities, the people of Asana are getting only small quantities of low-quality obsidian? In addition, this low-quality obsidian comes from Aconcahua, a source adjacent to Qillqatani?

Given the pattern of early Chivay obsidian at Asana, these Terminal Archaic distributions suggest that the high sierra residents at Asana were not participating in an altiplano-based circulation of goods as the Qillqatani residents. The residents of Asana never again participate in the circulation and consumption of Chivay obsidian, while at Qillqatani the consumption of Chivay material continues strongly for another one thousand years.

Other obsidian types during the Terminal Archaic

Obsidian from alternative sources in the circum-Titicaca region, including the unlocated sources of Tumuku and Chumbivilcas types, are used in greater quantity during the Terminal Archaic judging from associated projectile point evidence provided in Burger et al.(2000: 280-284).

Evidence from close to the Alca obsidian source provides new information about long distance interaction during Terminal Archaic. At the site of Waynuña at 3600 masl(Jennings 2002: 540-546)and less than one day's travel from the Alca obsidian source, recent investigations have uncovered a residential structure with evidence from starch grains resulting from the processing of corn as well as starch from arrowroot, a plant necessarily procured in the Amazon basin(Perry, et al. 2006). Given the long distance transport of arrowroot, it is conceivable that the plant material arrived as a form of reciprocation or direct transport from travelers moving between the Amazon and the Alca obsidian source. The Cotahuasi valley also has major salt source and other minerals that would potentially draw people procuring such materials. The starch samples were found in a structure on a floor dated by two14C samples. One sample was dated to 3431±45 (BGS-2576) 1880-1620 BCE, and another was 3745±65 (BGS-2573) 2350-1950 BCE

Further north, the Quispisisa type obsidian was particularly abundant during the Terminal Archaic at the preceramic coastal shell mound site of San Nicolas, along the Nasca coast, in a context associated with early cotton(Burger and Asaro 1977;Burger and Asaro 1978: 63-65). Quantitative data on the consumption of obsidian at San Nicolas are unavailable and the temporal control is weak because the "cotton preceramic" date is derived from association with cotton and no ceramics, not from direct14C dating.

Discussion

The distribution of obsidian from all three major Andean obsidian sources: Chivay, Alca, and Quispisisa, expanded considerably during the Terminal Archaic. It is notable that both the Chivay and Alca sources expanded, but the distribution remained confined to the sierra and altiplano areas of the south-central Andes. In comparison, obsidian from the Quispisisa source (340 linear km to the north-west of the Chivay source), has been found in significant quantities in Ica on the coast of Peru. While many of the early coastal obsidian samples have weak chronological control, the quantities of Quispisisa obsidian found in possible Archaic contexts is noteworthy. The fact that Chivay obsidian has never been found in coastal areas, and Alca is not found on the coast after the Paleoindian period, is remarkable considering the extensive evidence of coastal use of Quispisisa obsidian beginning in the Terminal Archaic.

Early Formative Period (2000 - 1300 BCE)

In this time period, new socio-economic patterns became well established in the south-central Andes while the distribution of Chivay obsidian was at its maximum both in geographic extent and in variability of site types. During this time period, societies were characterized by sedentism, demographic growth, increased specialization, and early evidence of social ranking(Aldenderfer 1989;Craig 2005;Stanish 2003: 99-109).

At sites like Jiskairumoko in the Titicaca Basin, architecture from the Terminal Archaic consisted of pithouses with internal storage, ground-stone, and interments with grave goods that included non-local items (like obsidian) that were presumably of value(Craig 2005). During the Early Formative around 1500 BCE this architectural pattern gives way to larger, rectangular, above-ground structures that lacked internal storage.

As reviewed by Burger et al. (2000: 288-296) using the Ica "Master sequence" chronology under the roughly contemporaneous "Initial Period" (though the Early Formative ends 300 calendar years earlier), the distributions of obsidian are notable in their extension both north and south from the Chivay source, and in their concentrations at early centers like Qaluyu. Obsidian from Chivay also persists on the Island of the Sun in the Early Formative(Stanish, et al. 2002).

Chivay obsidian distributions

At Qillqatani, obsidian flakes are available in quantity during this Titicaca time period which roughly overlap with the Formative A and B (XTable 3-5X). Seven obsidian samples were analyzed at MURR that all corresponded with the Chivay source. These samples were found in levels adjacent to a context that dated to2940±70bp (Beta-43925; 1380-970 BCE).

It appears that obsidian was being obtained as nodules or blanks and being knapped down to projectile points. Obsidian flakes represent 15% by count (n = 160) of all the flakes in the period "Formative A", and obsidian projectile points represent 12% by count of all points in this level(Aldenderfer 1999).

Obsidian is first found at Qaluyu dated to ~3250 uncal bp which calibrates to 1640-1420 BCE(Burger, et al. 2000: 291-296), or the end of the Early Formative where Burger et al. report evidence of nodules or blanks arriving for further reduction at the source. Some of the Chivay obsidian found at Qaluyu were medium sized pebbles; one example Burger et al. analyzed had the dimensions 1.9 x 1.4 x 1.2 cm. Qaluyu is 140 linear km from the Chivay source, or 34.6 hours by the hiking model, so it is roughly 70% of the distance of Qillqatani from the source. There are substantial quantities of obsidian at Qaluyu during the subsequent Middle Formative.

Discussion

Paleoclimatic studies have documented a decline in abundance of arboreal species in the Lake Titicaca Basin and an increase in open-ground weed species reflecting disturbed soils after ca. 1150 cal BCE(Paduano, et al. 2003: 274). This has been interpreted as reflecting intensification in food production and population that occurred during the Early Formative. Some argue that the grasslands of the altiplano are an anthropogenic artifact of a human induced lowering of the treeline due in part to the expansion of camelid pastoralism(Gade 1999: 42-74). The increasing sedentism, cultivated plants, expanding camelid herds and the growing influence of prominent settlements like Qaluyu in regional organization signify that significant socio-economic dynamism was underway by this period. The evidence of hierarchy takes the form of "very moderate social rank" acquired by certain individuals, such as religious specialists(Stanish 2003: 108). These traits are first suggested by jewelry, grave goods, and non-residential structures in the Terminal Archaic, but they become further elaborated during the Early Formative after 2000 BCE.

There is no evidence of political ranking in the structure of settlement distributions between Early Formative sites in the Lake Titicaca Basin, and all the sites are less than one hectare in size(Stanish 2003: 108), but the evidence of obsidian circulation from Qillqatani and other pastoral sites suggests of regional exchange system not yet focused around Lake Titicaca. Evidence acquired from the earliest occupational levels at Titicaca Basin regional centers suggest that regional interaction was low. At the site of Chiripa, in the southern Lake Titicaca Basin, Matthew Bandy describes traces of sodalite beads, obsidian, and sea shell in excavations from Early and Middle Formative contexts.

It is clear, then, that long distance trade in mortuary and prestige items took place as early as the Early Chiripa phase [1500-1000 BCE]. Equally clear, however, is that this early exchange involved very small quantities of the objects in question. This trading would seem to have been very sporadic and infrequent. There is no evidence in the Early Formative Period for the sort of regular caravan trade postulated by Browman (his "altiplano mode"; see Browman 1981: 414-415) (Bandy 2001: 141).

However, the evidence for obsidian distributions at Qillqatani that are discussed here point to routine exchange, perhaps by caravan trade, along on the Western Cordillera in the Early Formative. It appears that future regional centers like Chiripa were not yet participants in these exchange networks.

The dynamic nature of interregional interaction that occurred during the Early Formative is evident from the diversity in obsidian types at sites, and the lack of geographical restrictions that appear to structure exchange during later periods. While settled communities were evident, the lack of hierarchy and centralization suggests that they were not integrated by supra-local organization. Yet the economic basis for long distance relationships appears to have taken form by the Early Formative. The decentralized and variable nature of exchange in this period, which is abundantly evident at Qillqatani and yet not evident at sites like Chiripa, implies that another form of integration was linking communities, like the residents of Qillqatani, with the Chivay source 221 km to the north-west.

Middle Formative Period (1300 - 500 BCE)

During the Middle Formative Period, social ranking became established in the Titicaca Basin. The changes are most evident in the settlement structure as some regional centers grew to become far larger than their neighbors and feature sunken courts, mounds, and specialized stone and ceramic traditions. Stanish(2003: 109-110)interprets these changes in terms of an ability of elites to mobilize labor beyond the household level.

The stylistic evidence suggests that during the Middle Formative the north and south Titicaca Basin were relatively separate spheres, with Qaluyu pottery in the north and fiber-tempered Chiripa ceramics in the south extending only as far north as the Ilave river. However, Chivay obsidian is encountered in both the North and South Basin. Christine Hastorf (2005: 75)suggests that by the end of this period (the Early Upper Formative) evidence of ethnic identity and ritual activity is supported by ritual architectural construction and non-local exchange goods. It is further inferred that "Plants such as coca ( Erythroxylumsp.), Anadenanthera ( A. colubrine, A. peregrine), and tobacco (Nicotiana rustica)surely would have been present in the Basin by this time, perhaps associated with snuff trays…"(Hastorf 2005: 75). An increase in long distance exchange is commonly found as part of a complex of features associated with ideological and social power during the Middle Formative in the region, and it appears that existing exchange routes, such as the one along the Western Cordillera connecting Chivay with Qillqatani, were increasingly routed towards the Titicaca Basin regional centers during this time.

Chivay obsidian distributions

Chivay obsidian occurs in small quantities at a number of Middle Formative sites in the southern Basin including Chiripa and Tumatumani, and it persists at Ch'uxuqullu on the Island of the Sun. At Tumatumani, 3% of the projectile points are made from obsidian(Stanish and Steadman 1994). Bandy(2001: 141)reports that at Chiripa they recovered only small quantities of obsidian in the time spanning 1500-200 BCE and these were in the form of finished bifaces. For the entire time span, after four excavation seasons, they report only 87.1g of obsidian. Tumuku type obsidian was identified in Chiripa in Condori 1B component circa 1500-1000 cal BCE levels(Browman 1998: 310, dates calibrated). At the site of Camata, on the lakeshore south of the modern city of Puno, four obsidian samples were analyzed from contexts that range from circa 1500 - 500 cal BCE and all four were of Chivay type obsidian(Frye, et al. 1998;Steadman 1995).

The evidence from the North Titicaca Basin regional centers is even more intriguing as there is a significant presence of Alca type obsidian during the early part of the Middle Formative, and Chivay obsidian is found in the Cusco Basin during this time. Qaluyu, Pikicallepata, and Marcavalle all contain both Chivay and Alca obsidian between approximately 1100 - 800 cal. BCE, the early part of the Middle Formative(Burger, et al. 2000: 292;Chávez 1980: 249-253). Subsequent to this overlap in obsidian use, there appears to have been significant overlap in other stylistic attributes as well. These similarities include common traits in ceramic vessel forms between Chanapata vessels in the Cusco area and Qaluyu vessels in the North Titicaca Basin(Burger, et al. 2000: 292).

However, during the latter part of the Middle Formative after 800 BCE the Yaya-Mama religious tradition first emerges at the site of Chiripa(Bandy 2004: 330;Chávez 1988), a tradition that eventually unifies the north and south areas of the Titicaca Basin during the Late Formative. As noted by Burger et al.(2000: 311-314), with the appearance of the Yaya-Mama tradition the Alca and Chivay obsidian distributions become more asymmetrical. Alca obsidian makes up 16% (n = 9) of the obsidian in a pre-Pukara context at the site of Taraco on the Titicaca lake edge in the North Basin, however while Chivay obsidian was found at Marcavalle and other Cusco sites previously during the Early Formative, obsidian from the Chivay source is absent during the Middle Formative and it does not re-appear in the Cusco region again until the Inka period. Alca obsidian, on the other hand, expands outward during this period as it is found in the Titicaca Basin to the south-east, and it is also is transported a great distance to Chavín de Huantar. Both of these examples of long distance transport have been attributed to religious pilgrimage(Burger, et al. 2000: 314).

Qillqatani

At Qillqatani, the Middle Formative comprises the bulk of Formative B layers and all of the Formative C layers (see Qillqatani data in Section X3.4.2X). In Formative B layers, Chivay obsidian is the only type represented in the four samples that were analyzed and the lithic assemblage suggests that formal tools were not being produced at the site as no evidence of obsidian tools were found in these levels. Obsidian flakes, however, persist as 18% of the lithic assemblage from that level. Subsequently, in the Formative C level that begins around 900 BCE and corresponds approximately with the latter half of the Middle Formative as well as the rise of the Yaya-Mama tradition in the south Titicaca Basin, there is a distinctive shift in the use of obsidian at Qillqatani. Whereas all prior obsidian samples from Qillqatani were Chivay after the initial Middle Archaic sample, the obsidian samples in Qillqatani Formative C levels are only 60% from the Chivay source.

The other samples come from Aconcahua, a source of lower-quality obsidian that is near the Qillqatani shelter, and from Tumuku, an as-yet undiscovered source that may be located close to the three-way border between Peru, Bolivia, and Chile, and finally Alca obsidian occurs for the first and only time at Qillqatani in these levels. Given that Alca obsidian also occurs at Pukara, Incatunahuiri (surface) and at Taraco in quantity (16% of assemblage, n = 9), the presence of Alca obsidian at Qillqatani is consistent with the abundance of Alca material in circulation in that time. A sample of Alca obsidian has also been found on the Island of the Sun (Frye, et al. 1998), though it was from a surface context.

Table 3-6Xshows that obsidian tools in Formative C levels at Qillqatani are abundant (n = 19) and relatively large on average (1.21 g), and the non-obsidian tools were also very abundant (n = 187) for this level.

Discussion

Middle Formative obsidian distributions appear to demonstrate the emergence of a distinctive Titicaca Basin exchange sphere. One could argue that the emerging elites that mobilized labor to build the initial mounds and courts, and sponsored specialized artistry in stone and ceramics, may have precipitated a demand for greater exotic exchange goods as a source of prestige. Stanish(2003: 162)believes that this is the process that occurs later, during the Late Formative, when he argues that this process is connected to wealth generation for sponsoring feasts and other activities, though he admits the data are sparse. Evidence of long distance exchange from contexts belonging to the Early Formative and first half of the Middle Formative (1500-1000 BCE) at sites like Chiripa are sparse, irregular, and generally involve very small, portable goods; however the evidence from Qillqatani supports other models of more regular interaction along established exchange routes.

Late Formative Period (500 BCE - AD 400)

During the Late Formative, significant social ranking developed and dominated the socio-political landscape in the Lake Titicaca Basin. The complex polities that emerged on either end of Lake Titicaca were distinguished by architecture, stoneworking, and ceramic traditions. A three-tiered site size hierarchy is evident in the Late Formative, and the construction of prominent terraced mounds with sunken courts occurred in a few major sites at this time. The elite ceramics and stoneworking, and the construction of elaborate mounds as a venue for large-scale feasts and human sacrifice at sites like Pukara and early Tiwanaku, can be interpreted as a means of demonstrating the large-scale organization of labor by elites (Stanish 2003: 143).

The patterns of obsidian circulation that emerged at the end of the Middle Formative became very well established in the Late Formative. Excavations at centers in the North Basin have found a reduction in the presence of Alca obsidian in the Titicaca Basin, but the Alca material is still present although it is found in minor quantities at the larger sites as compared with Chivay obsidian. The diversity of obsidian types in the Titicaca Basin samples reported by Burger et al. (2000: 306-308) for this time span is low, as compared with the diversity of types used in the Cusco area, because in the Titicaca Basin it is virtually all Chivay obsidian.

In recent excavation work at Pukara on the central pampa at the base of the Qalasaya, Elizabeth Klarich (2005: 255-256) found that obsidian was generally available and obsidian use was not associated with any intrasite status differences. Probable representations of obsidian points and knives appear in Pukara iconography, and small discs have been found at Pukara and Taraco that were possible ceramic inlays (Burger, et al. 2000: 320-321). The Late Formative Period on the southern end of the Titicaca Basin has small amounts of Chivay obsidian at Chiripa and Kallamarka. InGiesso's (2000: 167-168)review of lithic evidence from several Formative Period sites he found no obsidian use in these collections except for samples from Khonkho Wankane which recent research directed by John Janusek has revealed to be principally a Late Formative center. The furthest confirmed examples of transport of Chivay obsidian are these examples encountered in southern Titicaca Basin sites. The two furthest confirmed contexts for Chivay obsidian transport are represented bytwo samples from a Late Formative context at Kallamarka (Burger, et al. 2000: 308, 319, 323) and six samples found at Khonkho Wankane (Giesso 2000: 346), both about 325 km from the Chivay source, or 72 hours by the walking model.

At Qillqatani, the obsidian returns to being primarily Chivay type during the Late Formative although 1 out of the 9 obsidian artifacts analyzed from Late Formative levels was of the Tumuku type (SectionX3.4.2X). During the Late Formative there is a steady decline in the percentage of debitage made from obsidian at Qillqatani, a trend that continues in the Tiwanaku period.

In the Colca Valley, there are few traces of the Late Formative consumers of Chivay obsidian. As will be further explored in this research project, there is very little Qaluyu or Pukara material diagnostic to the Middle or Late Formative in the Chivay obsidian source region. Steven Wernke found a diagnostic classic Pukara sherd with a post-fire incised zoomorphic motif that resembles a camelid-foot from a Formative site above the town of Yanque in the Colca (Wernke 2003: 137-138).

Pukara materials are known to have circulated, probably through trade links, throughout the south-central Andes. Pukara sherds have been found in the valley of Arequipa in association with the local Formative Socabaya ceramics (Cardona Rosas 2002: 55). In the Moquegua valley, both Chiripa-related and Pukara pottery have been found (Feldman 1989), and a Pukara textile was found in a possible elite grave context in the Ica Valley (Conklin 1983).

Discussion

The decline in forest cover in the Lake Titicaca Basin beginning during the Early Formative intensified throughout the Formative Period. Between 2500 - 800 cal. BCE a decline in fine particulate charcoal was detected in a lakecore drawn from the southern end of Lake Titicaca's Lago Grande(Paduano, et al. 2003: 274). The pollen and charcoal record indicates thatforest cover finally disappeared around AD0, coincident with population increases and resource pressure associated with Late Formative Period socio-economic intensification.

The obsidian circulation during the Late Formative shows distinct patterns in the Titicaca Basin and in Cusco. In the Titicaca Basin, the diversity of sources is reduced, with virtually all the material coming from Chivay and Alca, and the Alca samples are primarily affiliated with a single period at Taraco. Even at the site of Qillqatani, the diversity is reduced as compared with the previous Middle Formative level (Qillqatani Formative C). Current evidence suggests that the economic circulation was more integrated and that it was probably under some form of control by the dominant regional centers of this time. The furthest confirmed evidence of Chivay obsidian transport is from among Late Formative contexts at Kallamarka and Khonkho Wankane.Yet, diagnostic evidence from Titicaca Basin Late Formative polities in the Colca valley area is scarce. Part of the difficulty in understanding the Formative at the Chivay obsidian source area is that the Formative ceramic sequence in the Arequipa highlands is still being refined.

Discussion and review of "Early Agropastoralists" obsidian

From the Terminal Archaic through the Formative Periods the circulation and consumption of obsidian expanded dramatically. Chivay and Alca obsidian is found in a wide variety of sites from isolated rock shelters to early regional centers, and it appears in consistent quantities that differ considerably from the intermittent nature of regional obsidian supplies in preceding periods. The increased circulation of obsidian is part of a spectrum of changes that began in the Terminal Archaic, but obsidian distribution patterns are particularly useful because they are quantifiable.

In some ways obsidian appears most closely linked to tasks associated with camelid pastoralism, such as shearing and butchering. However, in the central Andean littoral, Quispisisa obsidian is found in density in "cotton preceramic" and Initial Period (i.e., Terminal Archaic and Early Formative) coastal sites where presumably pastoralism, if present, was a very minor part of the economy. Furthermore, in the south-central Andean highlands obsidian is found in pastoralist rock shelters but also in regional centers, and the small discarded obsidian flakes and small projectile points do not appear to have served as adequate shearing implements due to their size.

Social complexity during first part of the "Early Agropastoralists" period is manifested most prominently along the Pacific littoral. In the coastal context of what is now the Department of Lima, in central Peru, monumental architecture dating back to 3000 BCE is well-established at the site of Aspero, and the transition to yet more monumental preceramic construction at sites slightly inland has been documented in recent research(Haas, et al. 2005;Shady Solis, et al. 2001). The shift inland is argued to be related, among other things, to the increased importance of harnessing labor surpluses through the production of cotton for anchovy nets and textiles, and to competitive monument building between elites. Evidence of exchange with highland and Amazonian groups is apparent in the form of tropical feathers and other non-local prestige goods. While these developments occurred over one thousand km to the north of the Chivay area along the Pacific coast, early complex organization is also reported in northern coastal Chile in the Chinchorro II and III traditions spanning the Late Archaic through the Middle Formative(Rivera 1991). A long history of cotton production for nets and textiles, imported wool textiles, elaborate burial traditions, and long distance exchange with the highlands and the Amazon characterize the later Chinchorro tradition. These regional patterns underscore the wide scope of the changes that occurred during the Early Agropastoralists time. It has been argued that the beginning of social inequality in the highland Andes may have been stimulated indirectly by demand for wool from aggrandizers in coastal societies(Aldenderfer 1999).

Returning to evidence from highland obsidian distributions, the widespread circulation of obsidian during the Terminal Archaic and Formative is perhaps best discussed in the terminology used in the historical model of Nuñez and Dillehay(Dillehay and Nuñez 1988;1995 [1979]). While this adaptationalist model has theoretical limitations, it serves as a useful alternative to evolutionary chiefdom models that assign a paramount role to central-places in exchange, despite the decline of central-place models in geography(Smith 1976: 24). Following the Nuñez and Dillehay model, it is possible that what is occurring in the Terminal Archaic and Early Formative is the emergence of regular exchange pattern between Qillqatani and Chivay that took the form of a caravan trade "axis" along the western Cordillera. This exchange pattern is among the earliest systematic and demonstrable cases of the circulation of diffusive items through largely homogenous altiplano terrain (XFigure 3-4X) in the pattern that has also been described as horizontal complementarity or the "Altiplano mode"(Browman 1981). Subsequently, during the Middle and Late Formative in the Titicaca Basin, former "axis settlements" like Qillqatani, and the Western Cordillera axis more generally, became relatively less important in long distance exchange relationships. Regional centers in the Titicaca Basin like Taraco, Pukara, Chiripa, Khonkho Wankane, early Tiwanaku, and other centers, expanded in influence during this period of peer-polity competition. In these circumstances, the acquisition and ceremonial use of exotic goods appears to have been an important part of the competitive strategies of aggrandizers. Other evidence for Titicaca Basin-based exchange dynamics include the possible production of hoes of Incatunahuiri olivine basalt at Camata around 850-650 BCE that were then transported and used in southern Titicaca Basin sites(Bandy 2005: 96;Frye and Steadman 2001). While the nature of the relationship between emerging elites in Titicaca Basin polities and caravan drivers that provided links between settlements throughout the region is difficult to describe with precision, it appears that interregional articulation became considerably more elaborate by the end of the Early Agropastoralist period.