6.3. Survey Results: Archaic Foragers Period (9000-3300BCE)

This temporal period spans the calendar years ~9,000 - 3,300 BCE and includes the preceramic periods of Early, Middle, and Late Archaic, but it specifically excludes the preceramic "Terminal Archaic" time when pastoralism began to constitute an important part of the economy. The Archaic Foragers period in the Upper Colca region refers to the time that begins with the first diagnostic artifact production in the region through to the adoption of a predominantly food-producing economy with the Terminal Archaic. This discussion will consider the first peopling of the region as well, although data from surface survey cannot address those events directly for lack of diagnostic materials. Survey results show that during this time all three survey blocks were important parts of the local economy, but the puna rim area of Block 2 appears to have presented the greatest opportunities for foragers.

In reviewing the survey results below, Archaic components encountered during survey are isolated by the following characteristics:

(1) The presence of lithic reduction debris

(2) The natural shelter potential or other locational characteristics

(3) An absence of ceramics

(4) The presence of projectile points diagnostic to an Archaic chronological period

(5) An absence of late (Series 5) projectile points

As was previously mentioned, because of the high incidence of multicomponent occupations at large sites in this volcanic region, it is relatively difficult to isolate the archaic component of larger sites.

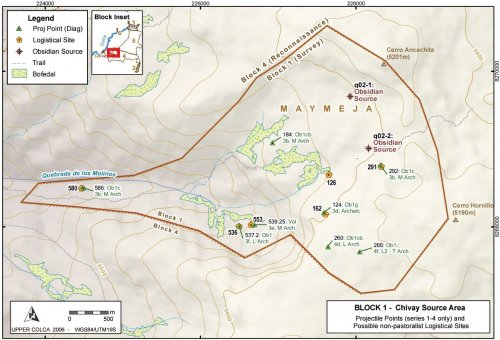

6.3.1. Block 1 - Archaic Source and adjacent high puna

Figure 6-6. Projectile Point weights and lengths (when not broken) by material type for Block 1 and adjacent high puna areas of Blocks 4 and 5. Series 5 projectile point types excluded.

Relatively few Archaic Period projectile points were identified in the Block 1 area. The obsidian points that were found in Block 1 are, unsurprisingly, relatively large and nearly all are incompletely flaked. This is consistent with the relative paucity of obsidian points among the Series 1-4 projectile points overall where Series 1-4 obsidian points were only 25% by count of all the obsidian points as shown in Table 6-14. This pattern is even more pronounced when one considers that Series 1-4 point styles were used for over 7000 years while the Series 5 types were used for only 4800 years, or 7/10 as long. Furthermore, as was discussed above, many of these Series 1-4 obsidian points were Ob2 material which further reduces the probability that they were procured in the Block 1 Maymeja area.

The Archaic Forager sites in Block 1

In the Maymeja portion of the Chivay source all surface archaeological materials diagnostic to time periods prior to pastoralism belonged to multicomponent sites with a substantial pastoralist component. This settlement pattern reflects the exposed, windy nature of the Chivay source: all sheltered areas that may have had overnight occupation were reused. No sites that could be termed "residential bases", using the same criteria as the other blocks of the Upper Colca project survey, were identified in this area.

Projectile points dating to the Archaic Foragers period were located in course of the survey of Block 1. Unsurprisingly, these points were virtually all obsidian, and most appeared to have been broken during manufacture with longitudinal breaks and incomplete scar coverage. In addition, it appears that broken non-obsidian bases were occasionally abandoned at the obsidian source, perhaps in the process of reusing the haft with newly fashioned obsidian points. For example, the base of a chert point with evidence of pressure flaking [A03-122] was recovered on the southern slopes of the Maymeja area during the survey work.

Figure 6-7. Possible Chivay obsidian source camps during Archaic Forager times.

Problems with isolating Archaic Foragers sites

One of the principal problems in isolating Archaic Foragers sites is that many of the artifactual indicators used in this research to designate sites as potentially belonging to the Early, Middle, or Late Archaic are not relevant in the obsidian source area. Of the three indicators that might potentially be used to designate sites from the Late Archaic or earlier, all three indicators have limitations.

(1) Aceramic sites.The use of ceramics in the high altitude obsidian source area appears to have been limited through the Formative Period (described in Section 6.4.1). Thus, the lack of ceramics is not evidence for a site dating to the preceramic.

(2) Material type ratios.A higher percentage of non-obsidian lithic material, primarily fine-grained volcanics, was used as an indicator of possible Archaic Foragers occupation in Block 3 of the survey area. This indicator doesn't apply to the obsidian source area, however, because virtually all flaked stone is obsidian in this area throughout prehistory.

(3) Diagnostic projectile points.Time sensitive projectile point styles continue to serve as indicators of temporal affiliation in the obsidian source area. However, as Block 1 consists of a lithic production area the projectile points found there were often incompletely flaked or broken during manufacture. As a result, a number of the projectile points did not belong to a particular point style.

The vast majority of scatters in the Maymeja area consisted of non-diagnostic scatters of obsidian with a high frequency of cortical flakes. It is possible that some of these scatters date to the period before the Terminal Archaic, and indeed many of these sites contain no ceramics. However, in this relatively high area remote from population centers, the fact that a site is a-ceramic cannot be taken as evidence that the site dates to the pre-ceramic. Given the intensification on obsidian production that occurred during the Terminal Archaic and onward, these non-diagnostic obsidian scatters are evaluated here as by-products of pastoral period intensification in the area.

Projectile Points

The human use of the Maymeja area dates to Middle Archaic (7000 - 5000 cal BCE) as is demonstrated by the presence of three transparent (one banded) obsidian projectile points of type 3b and one andesite point of type 3e depicted in Figure 6-6. The presence of 21 type 3b points in Block 2 (eight of them type 3b) indicates that the Middle Archaic occupation was predominantly a puna occupation. One of the type 3b points collected in the course of survey work was at "Molinos2" in the Quebrada de los Molinos at an elevation of only 4216 masl, suggesting that Molinos was used to travel between the lower elevation Colca Valley and the high altitude obsidian source and puna during the Middle Archaic.

Strong evidence of Early Archaic use of Chivay obsidian exists in the form of obsidian Early Archaic projectile points discussed among the data from the Block 2 and Block 3 areas of the survey, and in the early part of the Early Archaic at the site of Asana almost 200 km to the south-east. However, no Early Archaic projectile points were found in the Maymeja area of the Chivay source.

|

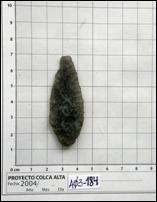

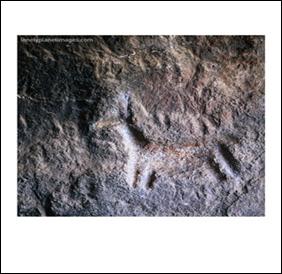

Figure 6-8. Middle Archaic obsidian projectile point from Maymeja area [A03-184]. |

The type 3B Middle Archaic obsidian point [A03-184] found on a moraine between two bofedales is the strongest evidence of early use of the Chivay source from the Maymeja area itself (Figure 6-8). A foliate point was identified that has one spine, pressure flaking, and it was found on a moraine at 4824 masl on the northern side of Maymeja that was perhaps glaciated during the Early Archaic. This projectile point represents the earliest date, judging from stylistic attributes, in Chivay source area. A10Be date was acquired from a quartzite sample collected from moraines at 4650 masl (Figure 4-15) that suggests that the entire Maymeja area was glaciated until circa 9000 cal BCE (Sandweiss, 2005 pers. comm.).

|

Period |

Point Type |

Obsidian |

Volcanics |

Chert |

|

Archaic |

3d |

124, 231.17 |

231.16, 780.3 |

|

|

M Arch |

2c |

110, 112 |

780.2 |

|

|

3b |

111, 184, 292, 586 |

780 |

||

|

3e |

539.25 |

|||

|

L Arch |

3f |

231.12, 537.2 |

||

|

4d |

260 |

|||

|

L2 - T Arch |

4f |

118, 266 |

Table 6-18. Diagnostic Projectile points Series 1-4 from Blocks 1, 4 and high altitude areas of Block 5, identifed by ArchID number.

Evidence from diagnostic projectile points suggest that during the Late Archaic, the use of Block 1 actually decreased because artifact counts drop from nine Middle Archaic projectile points to three Late Archaic points. Evidence from the entire survey area shows that the use of obsidian for projectile point production drops, beginning in the Late Archaic, from 65% to 52% of diagnostic projectile points. An alternative explanation for the reduced presence of diagnostic projectile points at the obsidian source is that the manufacture shifted to less advanced stages of reduction at the source such that diagnostic point styles were not recognizable in the source area.

|

Obsidian |

Volcanics |

Chert |

Column Total |

||

|

E., M., and L. Archaic (Series 1-4) |

No. |

13 (27.7%) |

4 (100%) |

1 (100%) |

18 (34.6%) |

|

mWt (g) |

11.0 (n=6) |

11.4 (n=1) |

5.0 (n=1) |

10.3 (n=8) |

|

|

sWt (g) |

6.2 |

- |

- |

5.6 |

|

|

by Sum Wt |

76 |

100 |

100 |

79.8 |

|

|

T. Archaic onwards (Series 5) |

No. |

34 (72.3%) |

- |

- |

34 (65.4%) |

|

mWt (g) |

1.74 (n=12) |

- |

- |

- |

|

|

sWt (g) |

1.1 |

- |

- |

- |

|

|

by Sum Wt |

24 |

- |

- |

20.2 |

|

Table 6-19. All Diagnostic Projectile Points from Blocks 1, 4, and Block 5 upper puna. Weights included for unbroken points only.

Comparing projectile points between the Archaic Foragers period and points belonging to the later periods demonstrates that, while counts are low for Series 1-4 points, the mean weight of projectile points (11g) is 6.3x larger than the mean weight of Series 5 projectile points. It should be noted that variability in Series 1-4 points is also much higher, with a standard deviation of more than one-half of the mean weight. This is consistent with size differences in the point types as described by Klink and Aldenderfer (2005) but it underscores the different quantities of material invested in point production at the obsidian source.

Site Type: Logistical Camps

Based primarily on the distribution of diagnostic projectile points and associated environmental data in the Maymeja area, it appears that "logistical camps" are prevalent in the settlement organization of the Chivay source area during the Archaic. Foragers likely visited the Maymeja area as an embedded strategy, combining obsidian procurement with hunting as the high relief area and talus boulders shelter a relative abundance of wildlife. Today, hunters visit the area to shoot viscacha, and a small population of vicuñaare occasionally seen in the area.

Site size estimates for logistical camps were not included in this portion of the study because all of these sites are multicomponent and, in most cases, obsidian scatter sizes more accurately reflect later periods with greater intensification of production.

|

Logistical |

Logistical Campss |

All Data |

All Data |

All data in B1m - Archaic Sitesm |

|

|

No. |

6 |

137 |

|||

|

Altitude (masl) |

4723.8 |

286 |

4806.8 |

215.1 |

-83 |

|

Slope (degrees) |

13.15 |

3.3 |

11.5 |

5.9 |

+1.65 |

|

Aspect (degrees) |

NW (83%) |

NW (45%), W (18%), SW (16%) |

|||

|

Visibility/Exposure |

8.5 |

7.1 |

15.1 |

11.9 |

-6.6 |

|

Dist. to Bofedal (m) |

257.7 |

223 |

219.7 |

275.3 |

+38 |

Table 6-20. Environmental characteristics of potentially Archaic Foragers logistical camps in Block 1.

The sites identified as possible Archaic Foragers logistical camps in this study are, on average, lower in elevation because the sample is small and one site in the low portion of Quebrada de los Molinos pulls down the average elevation. The sites are on slightly steeper slopes and they are predominantly on slopes with a northwest aspect at roughly twice the rate of the entire dataset of archaeological features in Block 1. The pattern of settlement location that prioritizes steeper slopes with a northwest aspect would ensure the maximum of afternoon sun and therefore higher temperatures. The viewshed analysis indicates that these locations are slightly lower visibility and exposure than is typical in the Block, although the standard deviation on these measures is quite high. Finally, the logistical camps are slightly further from bofedales than is typical in the Block 1.

The land-use patterns of these six potential logistical camps in the obsidian source area are consistent with models of forager behavior (Kelly 1992). In these models, access to water is not a top priority, as short stays at dry camps are common. Expedient shelters were probably used at these obsidian source logistical camps due to relatively high mobility and short stays. According to this locational model, places with higher ambient temperature would have been a top priority for logistical camps because of the generally cold environment and the limited built shelter offered in logistical camp construction. These settlements contrast with the later pastoralist settlement pattern that prioritizes access to pasture and water for the herd. It is sometimes difficult to differentiate small forager logistical camps from the common small pastoralist camps that were encountered on the tops of moraines and other exposed locations that have commanding views of bofedales where the herd was presumably grazing through much of the day.

However, as is apparent in Figure 6-7, only one pre-pastoralist projectile point style [A03-184] was identified on these exposed moraine sites in the center of the Maymeja zone, and this point was located relatively close to the obsidian exposures at 4900 masl. The point was found at an area later used by pastoralists (with good views of bofedales to the north and south), the site had no other features consistent with forager logistical sites in the area, and therefore it was not interpreted as such.

A03-580 "Molinos 2" [A03-580 - A03-586]

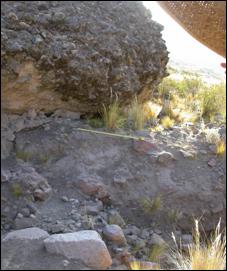

The lowest elevation site in Block 1 is "Molinos 2" [A03-580], at 4216 masl. It is located below a large breccia boulder that came to rest on a terrace on the south bank of Quebrada de los Molinos. The site is located along the principal trail that climbs up Molinos from the town of Chivay. The north side of the boulder serves as a small rock shelter with the following dimensions: width 5.5m, depth 2.1m, height 0.8m. The site has been bisected by a stream that has become heavily incised from torrential runoff events, perhaps most recently from the El Niño - Southern Oscillation of 1997-1998. The effect of this runoff on the archaeological site is twofold. First, the rock shelter has been filled in with debris, as is visible in Figure 6-9a, and the overall dimensions of the rock shelter have been greatly reduced as it was probably higher and perhaps deeper prior to the infilling. Second, the downcutting of the stream has revealed hundreds of flakes of obsidian and chert in profile in the terrace below (Figure 6-9b).

Figure 6-9. (a) Small rock shelter at "Molinos 2" [A03-580] is filled with debris from heavy runoff. (b) A density of flakes, predominantly of obsidian, are found in profile in the flood channel.

This site appears to have represented a regular travel stop between the obsidian source and the main Colca valley below. Projectile point evidence from the Early and Middle Archaic are relatively scarce elsewhere in the lower elevation portions of the survey, although 7% of the projectile points recovered during the Block 3 (Callalli) survey were characterized as Early and Middle Archaic. Steven Wernke's (2003: 541-542) survey in the main Colca valley found evidence of Early and Middle Archaic occupation at twelve sites in the form of diagnostic projectile points, and only one site (YA66) was below an altitude of 4000 masl.

A03-536 "Mamacocha 3" and A03-556 "Mamacocha 5"

These two sites share the characteristics of being located on lateral moraines that parallel the east-west direction of the Molinos drainage. Lithic scatters associated with large blocks of tuff that serve as small rock shelters are the principal features of these sites. A broken (longitudinally snapped) Middle Archaic 3e projectile point [A03-539.25] was found in one of these moraine sites; interestingly this point was made of andesite and was the only non-obsidian artifact found in this cluster of sites. A Late Archaic 3f obsidian point was also found in this area. Corral features and ceramics were identified here as well, indicating that the sites are multicomponent.

Figure 6-10. Lithic scatters are associated with shelter provided by large boulders located along moraines [A03-539]. One surveyor that is visible in blue provides scale.

The occupation of these sites was likely related to the use of resources in the upper Quebrada de los Molinos valley, although the moraines are not an obvious place for site locations. The sloping moraines are far from level and there is little open space between boulder, however the sites are probably located on these moraines due to factors that include insolation on these north-west trending moraines, the availability of water descending from Maymeja and the flanks of Hornillo, and the shelter offered by the large boulders.

A03-291 "Hornillo 9"

This high altitude site consists of an obsidian scatter that parallels a lava flow that trends northwest-southeast. The scatter is located in the sheltered area below the flow on ashy soil and while water is not presently available in this area, the site is level, it is relatively sheltered, and insolation is high.

Figure 6-11. Obsidian scatters were found on benches along the base of these viscous lava flows at 5040 masl [A03-291].

This site, and a neighboring site 70m downslope [A03-295] consist of obsidian scatters in areas sheltered by lava flows and the sites are adjacent to the lowest cost route out of the Maymeja area. The "Camino Hornillo" road [A03-268], described elsewhere, passes only 60m south-east of this area but, interestingly, no diagnostic artifacts were found that might connect these sites with the road. The only diagnostic artifact found at this site is A03-292, a possible 3b Middle Archaic projectile point with incomplete scar coverage made of clear Ob1 obsidian. At 5040 masl this projectile point represents the highest altitude diagnostic artifact found in the course of the survey. In some ways it is unsurprising that the only diagnostic point found at this site is from a time that predates camelid domestication: the camp offers no water or grazing and it would make little sense for herders to camp in this location when ample water and grazing opportunities lie on either end of Camino Hornillo.

A03-163 "Maymeja 4"

As shown in Figure 6-7, several diagnostic projectile points were found to the south-west of Maymeja. This access to the Maymeja area follows a trail that descends the lava flows from the western plateau of Cerro Hornillo. This trail is one of the most direct routes between the heavily traveled Escalera corridor to the south (in the Block 4 survey zone) and Maymeja. Just below the rim of the western plateau an obsidian scatter was found, along with one obsidian 3d projectile point [A03-124]; 3d is a style that is only diagnostic to the Archaic Period, generally.

At A03-255, another site approximately 500m to the south and on the broad rim of the Cerro Hornillo western plateau, another diagnostic obsidian projectile [A03-260] was found along with a number of ceramics. This area was a minor egress to the Maymeja area and perhaps was used by groups that were primarily interested in exploiting the bofedal in the lower part of Maymeja, and then crossing over to the Escalera area. It is also worth noting that the Camino Hornillo road [a03-268], along with a 4f Terminal Archaic projectile point [a03-266] were found just 500m east of here, but these features are interpreted as belonging to the Early Agropastoralist period described later.

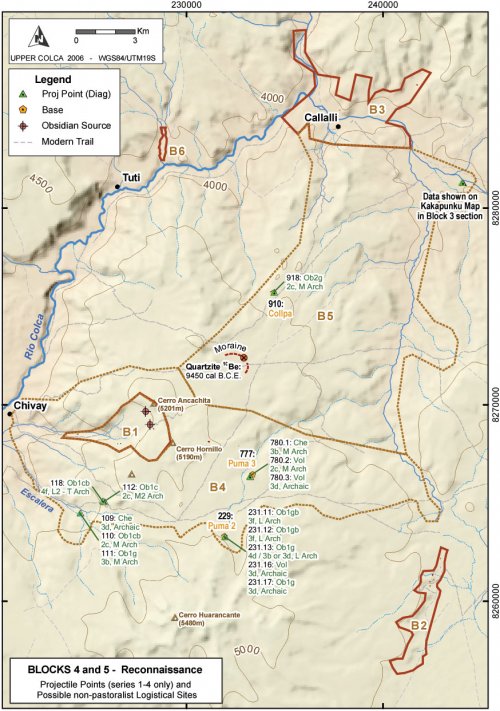

Blocks 4 and 5 Reconnaissance Areas

The expansive Block 4 and 5 areas were evaluated opportunistically rather than systematically in the course of the 2003 fieldwork; and these blocks were examined to a limited extent during preliminary research in 2002. The targeted nature of this work in these blocks precludes any systematic evaluation of site distributions and settlement patterns because of biased survey coverage, however hiking across these reconnaissance areas provides a measure of the variety in each block. Data from the survey of these reconnaissance blocks provide insight into the access that these zones offer to the Chivay source, as well as the initial obsidian production activities that occurred there.

Figure6-12. Map of project area showing Reconnaissance Blocks 4 and 5 with diagnostic projectile points and logistical sites from the Archaic Foragers period.

As with the settlement pattern in other lava rock areas of in the study zone, the arid and patchy environment of these blocks resulted in a relatively high rate of site reoccupation. The prevailing occupation pattern for the Archaic in Blocks 4 and 5 appear to consist of a few relatively large camps that are typically less than a few hundred meters from water, and often close to some kind of topographic prominence that offers both shelter and a view of the surrounding terrain. Isolated finds are also relatively frequent as should be expected of distributed subsistence, based on foraging.

The evidence points to an Early Holocene deglaciation of the Chivay Source area. A10Be date acquired from a quartzite erratic on a moraine to the east of the Chivay source area (data courtesy of Daniel Sandweiss, 2006), suggests that the terrain surrounding the source was glaciated at the 4650 masl level and higher as late as the Early Holocene (Figure 6-12and Figure 4-15). Establishing the rate of deglaciation for the different areas that may have been exposed in a given time period will require further glaciological study.

A03-229 "Puma 2" [A03-229 - A03-232]

This rock shelter, and the slopewash below it, is one of the more effective shelters occupied during the Archaic in this area. The shelter is above an active corral and immediately south of a medium sized estancia owned by the Puma family. At this rock shelter, a longer incidence of occupation is suggested by a higher density of lithics. The rock shelter itself is something of a tunnel with two entrances as a result of a collapse in the center portion of the shelter. Both entrances have had walls constructed across them, and the northern of the two walled entrances is visible in Figure 6-13.

Figure 6-13. Rock shelter [A03-229] passes behind the collapsed margin of the grey lava flow in the center of the photo. Walls are built to partially close off both of the two entrances.

This shelter faces the morning sun and perennial water is available in a stream approximately 300m east. Unfortunately the construction of a large corral, on a relatively steep (10°) slope (the upper wall of which is visible in Figure 6-13), has resulted in a great deal of disturbance for artifacts just below this shelter. The many projectile points identified here were found among the stirred-up debris at lower end of this sloping corral.

|

Ob1 |

Ob2 |

Volcanics |

Chert |

Total |

|

|

Biface |

1 |

1 |

|||

|

Biface Broken |

2 |

3 |

5 |

||

|

Flake Broken |

8 |

8 |

|||

|

Flake Complete |

1 |

1 |

2 |

||

|

Flake Retouched |

1 |

1 |

|||

|

Flake Retouched Broken |

1 |

1 |

2 |

||

|

Proj Point |

1 (3d) |

1 |

|||

|

Proj Point Broken |

5 (3f,3d,unk) |

1 (unk) |

6 |

||

|

Total |

9 |

5 |

1 |

11 |

26 |

Table6-21. Lithic artifacts from site A03-229 excluding eleven Series 5 projectile points.

This site contained a substantial number of points that are possibly Late Archaic, although the site also contained eleven Series 5 Term Archaic - Late Horizon points made from homogeneous Ob1 obsidian (that accounted for 60% of all projectile points by weight), but these were excluded from Table 6-1 because they are not Archaic. Based on the condition of the partially worked artifacts, much of this surface assemblage appears to have been abandoned during middle stage reduction in point production. One of the points was fine-grained volcanic, and had incomplete scar coverage. Of the obsidian artifacts, 45% of the projectile points and other bifacially flaked implements had incomplete scar coverage, and 66% were broken. These data suggest that this area, within a day's travel of the obsidian source, represented an intermediate stage in the lithic reduction trajectory as one departs the source. Interestingly, only 16% of the obsidian artifacts contained heterogeneities (Ob2) and these implements were nearly all classified as bifaces rather than as points. Ob2 obsidian was observed occurring as surface gravels only 4 km from this site, and the Maymeja source of Ob1 obsidian is nearly double that distance as the condor flies. Although this may be a signal from the later pastoral period, when shearing and other expedient uses for obsidian expanded, there appears to have been an emphasis on the use of Ob1 obsidian for point production while Ob2 obsidian was used for other bifacial tools.

Unfortunately, due to the disturbed state of the slope from the corral, and the artifact breakage that can result from animal trampling, further analyses of these data does not appear to be worthwhile. Future test excavations in the rock shelter may offer more insights into activities in this intermediate zone.

A03-777 "Puma 3" [A03-777 - A03-780]

As with the Puma 2 [A03-229] site higher in the valley, this site consists of a small shelter on the edge of a lava flow with improvements through the construction of rock walls.

|

Ob1 |

Ob2 |

Volcanics |

Chert |

Total |

|

|

Biface |

1 |

1 |

|||

|

Core |

4 |

4 |

|||

|

Flake Broken |

2 |

1 |

3 |

||

|

Flake Complete |

1 |

7 |

1 |

9 |

|

|

Flake Retouched |

1 |

1 |

|||

|

Heat-shatter |

1 |

1 |

|||

|

Proj Point |

1 (3b) |

1 |

|||

|

Proj Point Broken |

2 (2c,3d) |

3 |

|||

|

Total |

3 |

13 |

2 |

5 |

23 |

Table 6-22. Lithic artifacts from site A03-777 excluding 1 Series 5 projectile point.

Two patterns emerge from the lithic materials encountered at this site. First, the Pastoral period signature is weak as there is only one Series 5 point (and it was completely flaked, Ob1 material). The Archaic Foragers points are all Middle Archaic and they were made of volcanics and chert, not obsidian. A second notable pattern about these lithics is that it appears that there was reduction of primarily Ob2 obsidian at the site based on cores left at the site. These cores were not exhausted, one weighed 47 g and measured 4.5 x 4.1 cm. This is consistent with the evaluations of Ob2 obsidian more generally, in that it is used because it is widely available, yet there appears to have been a preference for Ob1 material and, in particular, for projectile point manufacture. This site is only 3 km from the exposures of surface gravels of Ob2 obsidian on the south-east flanks of Hornillo, but over 6 km from the Maymeja zone with the Ob1 material.

A03-910 "Collpa" [A03-910 - A03-925]

Collpa [A03-910] is approximately 9 km from the Maymeja area of the Chivay source, and it is also 8 km from Callalli to the north, therefore it is roughly equidistant between Block 1 and Block 3 survey areas. Collpa is an important site in this study because due to its position between the two survey blocks, it provides an opportunity to observe lithic consumption patterns midway between the obsidian source and the B3-Callalli zone. In fact, both the modern owner of Maymeja and his hired herder are from Callalli and this site of Collpa lies directly along their path from Callalli to Maymeja.

This site is located among a cluster of unusual-looking tuff outcrops that occur at the western extension of the Pichu formation to the south of Callalli (Ellison and Cruz 1985). This cartographic unit is described by the INGEMMET study as crystalline tuffs and ignimbrites. These outcrops are potentially in the same formation as the tuffs described and dated recently by Noble et al. (2003) as the ash flow sheets belonging to the "Upper Part" of the Castillo de Callalli section, a formation that was described above (Section 4.3.2). If so, then these tuff outcrops date to the Early Pliocene and are probably associated with volcanic activity at the Cailloma caldera to the north of the Colca valley.

Figure 6-14. Multicomponent site of A03-910 "Collpa" among crystalline tuff outcrops. Two dark figures are visible, standing apart in the right and center-right half of the photo, providing scale.

The site of Collpa [A03-910] contains predominantly Series 5 projectile points and is potentially, then, a pastoralist occupation however several projectile points dating to the Archaic Foragers were also found here. The reduction strategies applied in this area are summarized below, although it is difficult to establish if these data on reduction activities at Collpa reflect the Archaic Foragers time or to the later pastoralist period.

The site contains several small rock shelters but the principal lithic scatter is located on a high point in the grassy center of the Collpa area. The site has distinctive concentrations of obsidian and high intrasite variability, however the temporally diagnostic artifacts are not patterned such that one can differentiate components in these scatters. Thus, the site will be considered in one group here.

|

Ob1 |

Ob2 |

Volcanics |

Chert |

Quartzite |

Total |

|

|

Biface |

4 |

6 |

1 |

11 |

||

|

Core |

11 |

5 |

4 |

20 |

||

|

Flake |

98 |

32 |

8 |

29 |

2 |

167 |

|

Retouched Flake |

18 |

7 |

5 |

30 |

||

|

Hammerstone |

1 |

1 |

||||

|

Heat-shatter |

1 |

2 |

3 |

|||

|

Perforator Broken |

1 |

1 |

||||

|

Projectile Point |

6 (2c,unk) |

1 |

7 |

|||

|

Kombewa Flakes |

5 |

1 |

1 |

7 |

||

|

Bifacial Thinning |

8 |

1 |

1 |

10 |

||

|

Total |

190 |

10 |

42 |

2 |

244 |

Table 6-23. Lithic artifacts from site A03-910 excluding five Series 5 Ob1 projectile points.

The site contained a relatively high frequency of Kombewa flakes (also known as Janus flakes), a flake with bulbs of percussion on both ventral and dorsal surfaces that appears to have served as blanks for a Series 5 projectile point production. This is an artifact type that will be discussed in more detail in the discussion of the Q02-2u3 test unit at the Maymeja workshop in Chapter 7. Collpa contained a relatively high frequency of bifacial thinning flakes (n = 10) as per the calculated BTF index.

The material types in use at Collpa are consistent with the geographical position of this site as it lies half-way between the Maymeja zone of the Chivay source and Callalli. The Maymeja zone contains Ob1 obsidian, the eastern flanks of Hornillo contain Ob2 obsidian, and the area of Callalli in Block 3 contains abundant use of quartzite and chert that had often been heat treated. At Collpa [A03-910] a number of cores of both Ob1 and Ob2 chert were recovered.

|

No. |

mLength |

sLength |

mWeight |

sWeight |

|

|

Ob1 |

10 |

39.33 |

7.82 |

25.46 |

19.41 |

|

Ob2 |

5 |

34.26 |

13.67 |

15.98 |

19.72 |

|

Chert |

4 |

36.55 |

2.18 |

19.55 |

7.60 |

Table 6-24. Complete Cores at Collpa [A03-910].

Reduction in the Collpa site shows that there was provisioning occurring from both Maymeja and the eastern flanks of Hornillo where Ob2 obsidian is found, as well as chert being used that perhaps came from the Callalli area where chert is abundant. Ob1 cores are clearly dominant at this site. Ob1 is more common, larger, and heavier despite the greater distance to the Maymeja area where this study shows that Ob1 obsidian is found. It is difficult to establish the antiquity of the Callalli ownership of Maymeja, but if movement between Callalli and Maymeja is a pattern that has a long history, then perhaps the greater presence of Ob1 obsidian reflects this larger mobility pattern.

A03-109 through A03-118 "Escalera" Area

A number of Middle Archaic points, as well as other Archaic points, were identified along the major travel route climbing up from the Chivay area of the Colca valley to the puna; hence the name "Quebrada Escalera". This was a route out of the Colca valley that was widely used until the 1940s when alternative roads were improved. These projectile points are essentially isolates although the A03-109, 110, 111 projectile points were found in a small cache adjacent to a large corral - possibly due to salvaging and aggregation by the pastoralists that use the large corral.

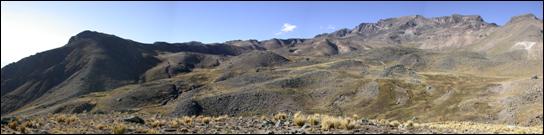

Figure 6-15. Photo of moraines and bofedales of Escalera south-west of Chivay source.

The region of Escalera contains extensive moraines interspersed with large bofedales due to the runoff from the glaciers of Nevado Huarancante. A major thoroughfare that bypasses the Chivay source to the south climbs through this valley following the moraines. This area contains varied habitat that probably offered relatively rich hunting throughout Archaic, as well as serving as a transition zone between valley and puna ecological zones.

Discussion

Distributions of diagnostic projectile points present the strongest surface evidence of Early, Middle, and Late Archaic activities at the Chivay source, and therefore inference about this period is strongly influenced by the production and discard of Series 1-4 point types in prehistory. Many of the obsidian projectiles found in the Block 1 survey and the Block 4 and 5 reconnaissance area had incomplete scar coverage, which is consistent with the reduction pattern one would expect near the source. The preferential use of Ob1 over Ob2 obsidian is evident from the core discard and the tendency to use Ob1 for projectile point production. The presence of Chivay obsidian at consumption sites, both locally and regionally, during the Early Archaic suggest that the source area was accessible during this time, there is no evidence of the use of the Maymeja area until the Middle Archaic.

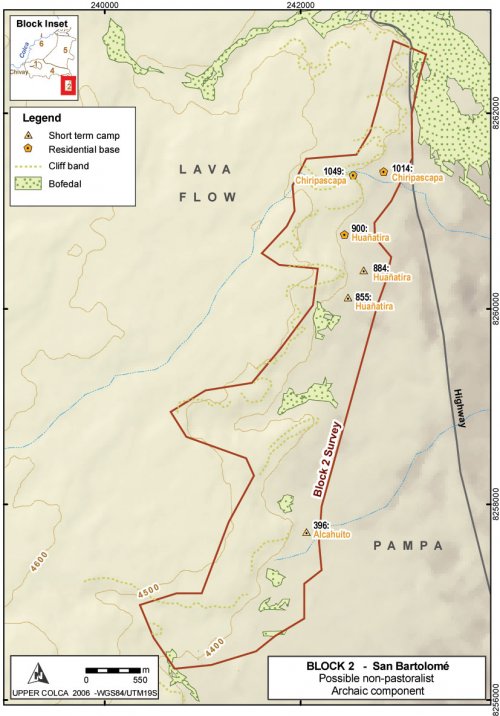

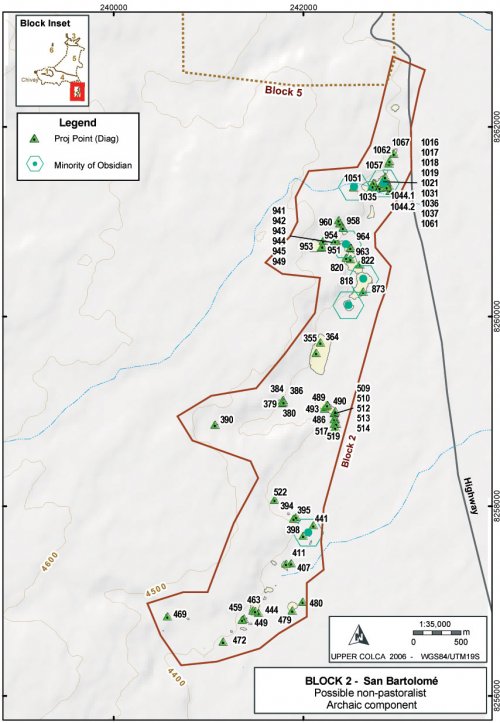

6.3.2. Block 2 - Archaic San Bartolomé

The Block 2 survey area parallels the edge of the Huarancante lava flow where geological features include the contact between the toe of a Pliocene lava flow and the open pampa. The pampa consists of ignimbrites weathering into a sandy soil and surface water in this area creates grassland with bofedales. Considering the study area on the whole, the greatest intensity of occupation during the pre-pastoralist Archaic appears to have taken place at San Bartolomé (Block 2). Sites in the area were surface collected in previous years by students from field classes at the Catholic University of Santa Maria in Arequipa (José-Antonio Chávez Chávez, Sept 2002, pers. comm.), but nevertheless a high density of projectile points was found in this area.

The evidence for long duration and diversity of activities comes primarily from the spatial distributions of projectile points and their material types. The San Bartolomé area was also an important zone during the subsequent pastoralist periods, due in large part to the rich bofedales mentioned above, that make differentiating pastoralist from Archaic Foragers (Early, Middle, and Late Archaic) occupations difficult. For foragers during the Archaic Period the area contains a rich mixture of reliable hunting opportunities and access to lower elevation vegetative resources in the Colca valley, two days travel away.

Projectile point distributions

Block 2 contained an abundance of projectile points diagnostic to the Archaic Foragers period. The wide variety of point types probably reflects the mobile strategies of Archaic foragers and the variable geology of the larger region.

|

Period |

Point Type |

Obsidian |

Volcanics |

Chalcedony |

Chert |

Quartzite |

|

Archaic |

3d |

489 |

449, 1019 |

394 |

||

|

E Arch |

1a |

355, 379, 380, 941, 1015, 1037, 1044.2 |

384 |

384 |

||

|

1b |

398, 411, 493, 522, 945, 956.3, 1026.3 |

444,514, 956.2 |

469, 1034 |

|||

|

E-M Arch |

2a |

512, 949 |

||||

|

L Arch |

3f |

490 |

390, 480 |

|||

|

4d |

960, 963, 964, 1017, 1018, 1024.4, 1024.5, 1048, 1067 |

|||||

|

Late Arch - T Arch |

4f |

407, 450, 463, 818, 943, 954, 1031 |

364, 1057 |

486 |

||

|

M Arch |

2c |

517, 873, 953, 1016, 1023, 1035, 1036, 1044, 1062 |

822, 1021 |

|||

|

3b |

386, 820, 944 |

958, 1051 |

509, 942 |

951 |

||

|

3e |

519 |

395 |

||||

|

MH |

4e |

472 |

Table 6-25. Diagnostic Projectile points Series 1-4 from Block 2 identifed by ArchID number.

Obsidian projectile points are extremely well represented in this area, but fine-grained volcanic material, primarily andesite, is also relatively abundant among the projectile point types except the Series 5 points. Chert and chalcedony points were present in Block 2, as well as chert knapping debris in low densities throughout the area, suggesting that chert nodules are available in relative proximity as well.

Figure 6-16. Projectile Point weights and lengths (when complete) by material type for Block 2. Series 5 points are excluded, chalcedony is included with chert, and quartzite is described separately.

Obsidian is well represented by count, but obsidian is typically smaller regardless of material type, even if the small, triangular Series 5 point types are excluded. An analysis of variance of material type showed that these differences between mean weights was extremely significant (F = 11.511, p> 05). Remarkably, even in this region, which is a day's travel from the Chivay source, obsidian appears to be used in the smaller size range of projectile points of the larger types.

Comparing the counts for weights and lengths in Figure 6-16 reveals that approximately one-half of the projectile points made from both obsidian and fine-grained volcanic materials are longitudinally snapped (and therefore no length measurement was taken). Thus, this difference in weights between obsidian and volcanics does not reflect differential breakage by obsidian points as it appears that the mean lengths of non-broken obsidian points are also roughly 8cm shorter than the mean lengths of fine-grained volcanic points. Other possible explanations for the smaller obsidian projectile points include the in-haft resharpening and other forms of recycling that would result in smaller sized obsidian points in the styles of larger types. The was evidence of resharpening noted on some projectile points, but a restudy would be required to examine resharpening evidence consistently in the collection.

Block 2 Archaic Foragers Settlement Pattern

Archaic Forager sites in the Block 2 portion of the survey fall into two major categories as indicated by the surface materials. One category of site consists of large sites that are sheltered in at least one sector of the site, and the other type of site appear as more diffuse scatters along the edge of the grassy plain that are largely intermingled with the pastoralist settlement pattern. These two kinds of sites will be discussed below, along with the characteristics of the artifacts found in each type of site.

Figure 6-17. Archaic Forager sites in Block 2: Major sites described in the text.

Site Type: Residential Base

Archaic Forager period sites take two principal forms in this survey block. Residential bases, with what appears to be a great deal of redundancy of occupation, were encountered in a few locations with distinctive attributes (like shelter from wind). Projectile points styles diagnostic to Archaic Foragers time periods are encountered in a variety of contexts that include some areas near bofedales that were later intensely utilized by pastoralists, and some areas that show more spatially distributed occupational histories.

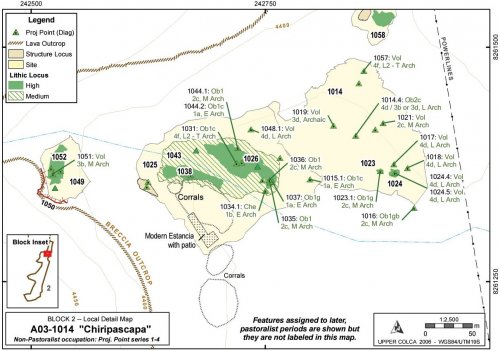

A03-1014 "Chiripascapa" [A03-1014 - A03-1057]

Chiripascapa was recorded as three sites due to variability in the artifact distributions and the differences in topography. Due to downslope movement in the steep talus zone in one portion of the site, and deflation in the lower site complex, the Archaic Foragers component of this site complex will be described as one group.

|

ArchID |

SiteID |

FileType |

Description |

Area (m2) |

|

1014 |

1014 |

Site_a |

"Chiripascapa" |

24,550,334 |

|

1023 |

1014 |

Lithic_a |

Medium Dens, 100 Obs |

38,785 |

|

1024 |

1014 |

Lithic_a |

Medium Dens, 89 Obs |

124,943 |

|

1025 |

1025 |

Site_a |

"Chiripascapa2" |

27,927,630 |

|

1026 |

1025 |

Lithic_a |

High Dens, 100 Obs |

2,470,331 |

|

1038 |

1025 |

Lithic_a |

High Dens, 30 Obs |

1,086,213 |

|

1041 |

1025 |

Ceram_a |

Painted LIP |

186 |

|

1043 |

1025 |

Lithic_a |

Medium Dens, 100 Obs |

9,484,728 |

|

1045 |

1025 |

Struct_a |

Wall Bases Only, Cave |

128 |

|

1052 |

1025 |

Lithic_a |

Medium Dens, 100 Obs |

888,906 |

|

1049 |

1049 |

Site_a |

"Chiripascapa3", Rock shelter |

3,657,074 |

Table 6-26. Loci in Chiripascapa

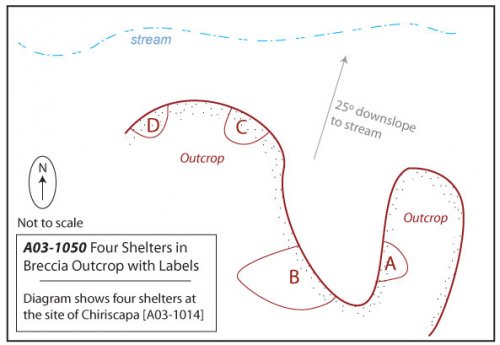

Description

The upper part of Chiripascapa consists of one medium sized rock shelter and three small rock shelters at the base of an east-north-east facing portion of the Huarancante volcanic breccia lava flow escarpment. Below the rock shelters a sloping talus field (a 25° slope), littered with lithics as well as ceramics, leads to a small intermittent stream 20 vertical meters below the rock shelter. On the banks of this stream is a scatter of lithics and ceramics from a variety of time periods that extend downstream for approximately 300 m. The south bank of the stream has a modern estancia (Pausa) and a large corral below the associated buildings, seriously disturbing any artifact scatters on the south bank. The north bank of the stream is also disturbed. Large scars from bulldozers scraped off the topsoil in certain areas. The resident at the Pausa estancia explained that during the 1970s highway improvement for the Majes Project the road crews caused these impacts as they were looking for gravel sources in that area. Just north of this site complex is a large, active gravel pit.

Figure 6-18. A03-1050 consists of four rock shelters: A, B, C, and D.

Figure 6-19. Chiripascapa [A03-1014], Archaic Foragers occupation.

A03-1050 - Four rock shelters of Chiripascapa

These rock shelters appear to be well situated with respect to the surrounding geography. The shelters face east-north-east and so despite being in a dark and slightly damp corner of the lava toe they catch the morning and midday sun. It is worth noting that the estanciadepicted in the center of the map appears to be deliberately built with the same aspect. The rock shelter is relatively well-hidden because it lies about 50m up a side quebrada and therefore goes unnoticed unless you climb the quebrada. Despite the concealed position, this location actually offers a partial view of the most important resource in the zone: the bofedal one km to the north-east. It would also be possible to monitor travel through the Ventanas del Colca access to the upper Colca from this hidden location. The stream below the shelters was dry at the end of the dry season, but probably flows most of the year.

Due to low GPS reception in the rock shelter area the four rock shelters were mapped as a single Struct-L line "A03-1050" and differentiated as A, B, C, and D. Only one shelter, the one designated as A03-1050B, had the characteristics of a residential shelter. The dimensions of this shelter are as follows. Height:2m, Depth:6.5m, Width:7m. Due to the overhanging roof formed from the lava flow, a considerable area is dry outside of the walls of the cave. This area shows signs of having been improved as a patio and the "patio" area extends the depth of the dry zone by another 12.5m. The rock shelter 1050A was large but wet, and 1050C and 1050D were very small but dry.

Below the rock shelters a talus slope extends approximately 20 vertical meters to the stream. A variety of lithics and ceramics were identified on this slope, though only one projectile point was diagnostic to a period that falls in the Archaic Foragers timespan. This point [A03-1051] was a Middle Archaic andesite point and it had a transverse snap and missing its haft element, suggesting that it was broken in use.

Features and Artifacts

The stream enters the open, sandy soils of the pampa and on either bank of the stream, though primarily on the north bank, projectile points from throughout the Archaic sequence were found. Preservation is relatively poor on this section of the pampa. In addition to the bulldozer impacts mentioned above, the soils appear deflated and this partly explains the high density of projectile points, from virtually every time period, found in this area. It seems possible that the entire site scatter was formerly more aggregated on the western part of this map, and with riverine transport the artifacts have been scattered over the pampa.

|

ArchID |

Artif. # |

Material |

Form |

Type |

Temporal |

|

1015 |

1 |

Obsidian |

Proj Point Broken |

1a |

Early Archaic |

|

1016 |

1 |

Obsidian |

Proj Point |

2c |

Middle Archaic |

|

1017 |

1 |

Volcanics |

Proj Point Broken |

4d |

Late Archaic |

|

1018 |

1 |

Volcanics |

Proj Point |

4d |

Late Archaic |

|

1019 |

1 |

Volcanics |

Proj Point |

3d |

Archaic |

|

1021 |

1 |

Volcanics |

Proj Point Broken |

2c |

Middle Archaic |

|

1023 |

1 |

Obsidian |

Proj Point |

2c |

Middle Archaic |

|

1024 |

4 |

Volcanics |

Proj Point |

4d |

Late Archaic |

|

1024 |

5 |

Volcanics |

Proj Point Broken |

4d |

Late Archaic |

|

1026 |

3 |

Obsidian |

Proj Point |

1b |

Early Archaic |

|

1031 |

1 |

Obsidian |

Proj Point |

4f |

Late-Term. Archaic |

|

1034 |

1 |

Chert |

Proj Point |

1b |

Early Archaic |

|

1035 |

1 |

Obsidian |

Preform |

2c |

Middle Archaic |

|

1036 |

1 |

Obsidian |

Preform |

2c |

Middle Archaic |

|

1037 |

1 |

Obsidian |

Proj Point |

1a |

Early Archaic |

|

1044 |

1 |

Obsidian |

Preform |

2c |

Middle Archaic |

|

1044 |

2 |

Obsidian |

Proj Point |

1a |

Early Archaic |

|

1048 |

1 |

Volcanics |

Proj Point |

4d |

Late Archaic |

|

1051 |

1 |

Volcanics |

Proj Point Broken |

3b |

Middle Archaic |

|

1057 |

1 |

Volcanics |

Proj Point Broken |

4f |

Late-Term. Archaic |

Table 6-27. Diagnostic Series 1 through 4 projectile points from Chiripascapa [A03-1014].

The temporal distribution of projectile points from Chiripascapa shows that virtually every time period is well represented. One distinction worth noting is that obsidian is used almost exclusively in the later time period, while about 50% of the projectile points (by count) are made from obsidian in the early time periods presented by Series 1 - 4 points.

|

Projectile Points |

Obsidian |

Volcanics |

Chalcedony |

Chert |

|

Series 1 - 4 |

10 (48%) |

9 (43%) |

1 (5%) |

1 (5%) |

|

Series 5 |

24 (96%) |

1 (4%) |

0 |

0 |

|

Total |

34 |

10 |

1 |

1 |

Table 6-28. Representative proportions of material types by projectile point styles.

The medium and high density lithic loci along the creek banks are difficult to temporally isolate because there are later period diagnostics, including twenty-six Series 5 projectile points and ceramics dating from the Middle Horizon, LIP, and Inka periods found in the A03-1038 lithic locus. Most of the flakes observed at this site were obsidian and chert. A small concentration of andesite flakes on the south bank of the stream in locus A03-1038 was observed, despite the fact that all andesite projectile points came from the north bank of the stream.

|

Material Type |

Obsidian |

Volcanics |

Chalcedony |

Chert |

Quartzite |

|

No. |

88 (62%) |

32 (23%) |

5 (4%) |

15 (11%) |

1 (0.7%) |

|

Mean Wt (g) |

5.05 |

18.28 |

16.7 |

10.91 |

11.5 |

|

% by Sum Wt |

34.5% |

45.6% |

6.7% |

12.3% |

0.9% |

Table 6-29. All lithic artifacts from Chiripascapa.

The surface materials included bifaces, cores, and flakes of all local material types except quartzite, which was rare at the site. Based on the mean flake size and the percentage of the total contribution by weight, fine-grained volcanics appear the most local to the area. Isolating any one of the lithic concentrations to a particular time period is difficult, but when viewed collectively including the point scatters in A03-1014 and A03-1025, and the rock shelters in A03-1049, the site complex is one of the oldest residential areas in the larger study area. The rock shelter A03-1050B and the built up patio has a high probability of containing a stratified intact deposit that extends into the earlier parts of the Archaic.

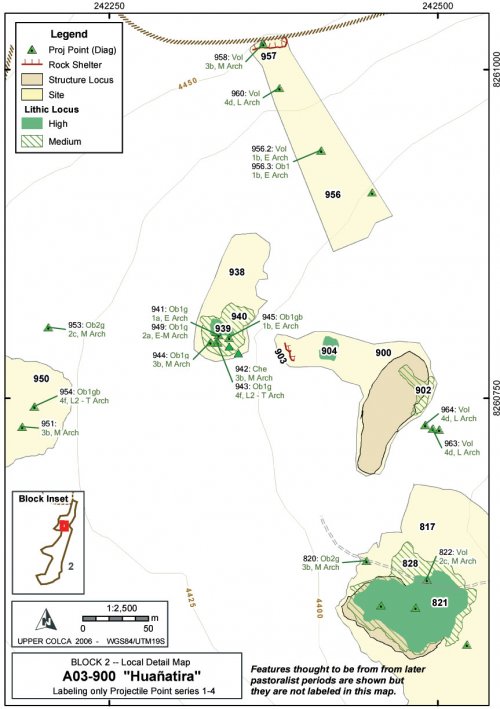

A03-900 "Huañatira"

Huañatira is a horseshoe-shaped valley with escarpments of lava flows of volcanic breccia on three sides and a small rise in the center where a single toe of lava extends down lower towards the pampa. The result is a sheltered, circular valley with a sloping ramp that climbs towards the top of the lava flow to the east of the valley. The Huañatira valley provides a moderately sheltered area with good views of the surrounding pampa, and it is defensive because it provides means of escaping to the higher lava flow terrain without being observed by pedestrians approaching from the pampa.

Figure6-20. Huañatira [A03-900] and vicinity, Archaic Foragers occupation.

Description

The area has evidence of occupation from virtually every time period from the Early Archaic to the modern period. A maintained estancia is found just to the west of the study area shown in Figure 6-20, and a small driveway is shown on the map accessing the area from the east. A worn trail departs the estancia to the west; a travel route that probably dates to the pastoral period if not earlier. Projectile points were found scattered around the valley that date to all periods, however most of the large scale archaeological features in this area appear to be from the pastoralist period. The circular or oval features shown as structural loci (not labeled on Figure 6-20) are most likely of pastoralist origin. A rock shelter offering partial protection was found in the center of site 900 overlooking the pampa [A03-903]. This immediate valley area belongs to a very small local watershed, and during the dry season there was no apparent surface water. This small watershed prevented a great deal of surface runoff; a factor has probably helped to maintain artifact positions in their original contexts in this local valley more than at other sites from the survey.

|

ArchID |

File Type |

ArchID (cont.) |

File Type |

|

|

817 |

site_a |

940 |

lithic_a |

|

|

820 |

site_p |

941 |

lithic_p |

|

|

821 |

lithic_a |

942 |

lithic_p |

|

|

822 |

site_p |

943 |

lithic_p |

|

|

823 |

site_p |

944 |

lithic_p |

|

|

824 |

site_p |

945 |

lithic_p |

|

|

825 |

site_p |

946 |

lithic_p |

|

|

826 |

site_p |

947 |

lithic_p |

|

|

827 |

site_p |

948 |

site_p |

|

|

828 |

lithic_a |

949 |

lithic_p |

|

|

830 |

struct_p |

951 |

lithic_p |

|

|

831 |

site_p |

953 |

lithic_p |

|

|

900 |

site_a |

954 |

lithic_p |

|

|

902 |

lithic_a |

956 |

site_a |

|

|

903 |

struct_l |

957 |

struct_l |

|

|

904 |

lithic_a |

958 |

struct_a |

|

|

905 |

lithic_p |

960 |

lithic_p |

|

|

906 |

site_p |

961 |

lithic_p |

|

|

907 |

site_p |

962 |

lithic_p |

|

|

938 |

site_a |

963 |

lithic_p |

|

|

939 |

lithic_a |

964 |

lithic_p |

Table 6-30. Non-consecutive ArchID numbers at Huañatira [A03-900], an Archaic Foragers site.

A03-957 - Rock shelter

This is a relatively large rock shelter overlooking the pampa and the valley of Huañatira. Contrary to most residential rock shelters in the region, this shelter faces south-east and it is therefore not exposed to the warming sun and was probably a shelter that was cool in temperature nearly all year reducing its potential as a residential structure in the altiplano. The shelter offers a relatively large amount of residential space inside the dripline; the rock shelter is 7m deep from the dripline, 12m wide, and over 3m high. Virtually all of the interior space of the shelter is clear of rubble and useable for residential activities. Four projectile points from the Early, Middle, and Late Archaic Periods were found associated with this shelter. A recessed tomb dominates this shelter today, but given the size of the feature and the pattern of cave burial during the Late Intermediate Period, the mortuary feature in this shelter is interpreted as a LIP cist tomb. These features are described in the Late Prehispanic - Block 2 discussion (Figure 6-76), close to the end of this chapter.

Figure 6-21. Rock shelter of Huañatira with circular mortuary feature visible inside. One meter scale showing on tape resting on rock along dripline (see also Figure 6-76).

Features and Artifacts

Some cases of disturbed artifact provenience are obvious, such as the three projectile points in a wash at the base of the valley shown as the three points on the eastern edge of Figure 6-20. Also the points below the Huañatira rock shelter on the north end ofthis site were found in the colluvial zone below the shelter and were apparently displaced.

|

ArchID |

Index# |

Material |

Form |

Type |

Temporal |

|

820 |

1 |

Obsidian |

Proj Point |

3b |

Middle Archaic |

|

822 |

1 |

Volcanics |

Proj Point |

2c |

Middle Archaic |

|

941 |

1 |

Obsidian |

Proj Point |

1a |

Early Archaic |

|

942 |

1 |

Chert |

Proj Point Broken |

3b |

Middle Archaic |

|

943 |

1 |

Obsidian |

Proj Point |

4f |

Late - Terminal Archaic |

|

944 |

1 |

Obsidian |

Proj Point |

3b |

Middle Archaic |

|

945 |

1 |

Obsidian |

Proj Point |

1b |

Early Archaic |

|

949 |

1 |

Obsidian |

Proj Point |

2a |

Early-Middle Archaic |

|

951 |

1 |

Quartzite |

Proj Point |

3b |

Middle Archaic |

|

953 |

1 |

Obsidian |

Proj Point |

2c |

Middle Archaic |

|

954 |

1 |

Obsidian |

Proj Point |

4f |

Late - Terminal Archaic |

|

956 |

2 |

Volcanics |

Proj Point Broken |

1b |

Early Archaic |

|

956 |

3 |

Obsidian |

Proj Point Broken |

1b |

Early Archaic |

|

958 |

1 |

Volcanics |

Proj Point Broken |

3b |

Middle Archaic |

|

960 |

1 |

Volcanics |

Proj Point |

4d |

Late Archaic |

|

963 |

1 |

Volcanics |

Proj Point Broken |

4d |

Late Archaic |

|

964 |

1 |

Volcanics |

Proj Point |

4d |

Late Archaic |

Table 6-31. Diagnostic Series 1 through 4 projectile points from Huañatira [A03-900].

Artifact proportions are consistent with other Archaic Foragers sites in the area, with approximately 50 of the projectile points and 65 of all collected lithic artifacts being of obsidian. A number of bifaces and flakes were found at this site, primarily of fine-grained volcanic stone and obsidian, and one obsidian core.

|

Material Type |

Obsidian |

Volcanics |

Chalcedony |

Chert |

Quartzite |

|

No. |

50 (64%) |

14 (18%) |

3 (4%) |

9 (12%) |

2 (3%) |

|

Mean Wt (g) |

4.97 |

99.8 |

31.4 |

49.5 |

111.1 |

|

% by Sum Wt |

10.4% |

57.8% |

4.2% |

17.6% |

9.9% |

Table 6-32. All lithic artifacts from Huañatira.

As with other residential areas in Block 2, it is difficult to differentiate the Archaic Foragers component in this area of heavy reoccupation. The area contains a large rock shelter and it provides a measure of shelter on the border of the pampa, as do the other shelters in the area. Several Late Archaic projectile points are dark fine-grained volcanic rock, akin to the Late Archaic (4d) points found at that Chiripascapa [a03-1014] a short distance to the north.

Site Type: Sites with majority non-obsidian lithics

A substantial Archaic presence in Block 2 takes the form of diffused, low density scatters with associated diagnostic projectile points along the edge of the pampa and frequently close to water sources. These finds are very difficult to differentiate from the pastoralist site occupation pattern and therefore these features will be described as a group, followed by generalizations about the characteristics of the environmental and cultural features of sites of this type in Block 2.

While the Archaic Foragers use of space largely overlaps with pastoralist occupation areas in Block 2, the use of lithics appears to differentiate the two. As was discussed in Chapter 3 (Section 3.4.4), the use of obsidian for projectile points expands dramatically at the end of the Archaic Foragers period both near the Chivay source and in the consumption zone.

Figure 6-22. Block 2 Archaic Foragers component from lithic evidence.

Method

The criteria used here for sites isolating through the dominance of particular material types are as follows for both lab analysis Lithics_I and Lithics_II. First, the lab results by SiteID (or isolated ArchID), showing count and percent, were shown in a table against material type in Arcmap. This table was joined to the All_ArchID_Centroids point geometry [link to Processing in Ch 5] so that lab results for lithic material types were aggregated by site or isolate. These features were then filtered by constructing a query where the artifact count for a geographical feature had to be greater than 5 so that relative percentages were meaningful. Finally, the index symbolized inFigure 6-22 is the Lithics_I lab results (the most comprehensive table) where Percentage of Non-obsidian lithic artifacts is greater than or equal to 50%.

Results

The use of non-obsidian materials such as chert, chalcedony, and especially fine-grained volcanic materials, dropped precipitously during the Terminal Archaic at sites in Block 2. While all lithic material types persist in use during the pastoral period, the herd management tasks of butchery and shearing appear to have been largely conducted using obsidian. Reviewing the percentages of sites with strong evidence of a pastoralist occupation (only Series 5 projectile points, a corral, water, and grazing opportunies) these sites commonly have between 20% - 40% non-obsidian flaked stone. Thus, the distinction between pastoralist and forager components based on material type is not firm, but the distributional pattern is reinforced by non-series 5 projectile point distributions, and this evidence is shown together in Figure 6-22.

Six sites have been identified with a relatively robust Archaic Foragers component in Block 2 and the environmental characteristics of these six sites will be compared with all locational characteristics of B2 sites in order to look for patterning among the environmental criteria of Archaic Foragers sites. These six sites include the following A03- 396, 884, 894, 900, 1014, 1049 and while diagnostics from the Archaic Foragers period were widely encountered throughout the region, these sites are selected as representantive for the larger Archaic Foragers time period and life way based on inference. Clearly the boundaries of the "site" are probably not coterminous with the Archaic Foragers component of these sites, nevertheless these measures serve as a general indicator of changes in the environment context of settlement through time.

|

Selectedm |

Selecteds |

All B2 Sitesm |

All B2 Sitess |

All B2 Sitesm - Selectm |

|

|

Altitude (masl) |

4382.6 |

12.69 |

4393.2 |

25.7 |

-10.6 |

|

Slope (degrees) |

7.86 |

8 |

8.33 |

6.34 |

-0.47 |

|

Aspect (degrees) |

146.5 |

96.4 |

138.4 |

58.23 |

8.1 |

|

Visibility/Exposure |

33.6 |

13.1 |

40.1 |

25.53 |

-6.5 |

|

Dist. to Bofedal (m) |

497.3 |

212.2 |

307.5 |

261.5 |

189.8 |

Table 6-33.Environmental characteristics of selected Archaic Foragers sites in Block 2.

The high standard deviation values in the Table 6-33 "Selected sites" underscores the variability and inconsistency in these estimates. This comparison shows that the Archaic Foragers sites tend to be more sheltered/lower visibility than the pastoralist sites. As was previously noted, the Archaic Foragers sites are often adjacent to overlooks but the sites often do not occupy the high exposure area specifically. Archaic Foragers sites are considerably further than average from bofedales. This strong tendency in the data is probably accentuated by the intensification and maintenance of pastoral resources that has occurred in recent years. That is to say, as pastoralism is today the principal economy activity in the area, bofedales and attendant pastoral facilities have been well-maintained in the recent past, which is the criteria from which bofedales were selected from the ASTER satellite imagery for this measure. A further issue with respect to distance to water is the fact that many of the potential forager sites are adjacent to small streams that were probably seasonal and appear as dry in the modern dry-season ASTER imagery.

Discussion

Block 2 survey area represents a transition from the rugged lava flow topography on the west side of the block to the open pampa on the east side of the block. In addition, residents in the Block 2 area are able to exploit the higher density off resources in the puna while maintaining access and, perhaps, social relationships with residents in the adjacent lower altitude portions of the Colca valley.

A number of obsidian projectile points in this area were produced in the same general forms as chert points and, particularly, as fine-grained volcanic points. These forms are most akin to those documented at Sumbay, 30 km to the south. Given the greater local variability in point forms during the Late Archaic (Klink and Aldenderfer 2005: 53), the data from the Block 2 area provides an opportunity to study the local projectile point styles, best known from the Sumbay style points, in conjunction with the regional interaction documented through obsidian distribution data.

6.3.3. Block 3 - Archaic Callalli and adjacent valley bottom areas

The 2003 field season evidence shows that the Archaic Foragers period use of the river valley and adjacent puna appears to have been relatively light in comparison with the occupation in the B2 - San Bartolomé area. Diagnostic projectile points and aceramic sites represent the only strong evidence of Archaic Period occupation in Block 3 since only test excavations in B3, at the site of Taukamayo [A03-678], were dated to the early part of the Middle Horizon.

Projectile point distributions

The strongest evidence of human activity during the Archaic in the Upper Colca valley segment of the survey comes from projectile point distributions.

|

Period |

Point Type |

Obsidian |

Volcanics |

Chalcedony |

Chert |

|

Archaic |

3d |

599, 1080 |

25 |

10, 670, 810 |

|

|

E-M Arch |

2a |

1078 |

599.4 |

||

|

3a |

1001 |

34 |

|||

|

M Arch |

2c |

790.3 |

|||

|

3b |

1007 |

810.2 |

|||

|

Latter part of M Arch |

2b |

1002 |

|||

|

L Arch |

3f |

1099 |

|||

|

4d |

86 |

85, 1008 |

94 |

38 |

|

|

L2 - T Arch |

4f |

93, 809 |

Table 6-34. Diagnostic Projectile points Series 1-4 from Blocks 3, 6 and the valley portion of Block 5 identifed by ArchID number.

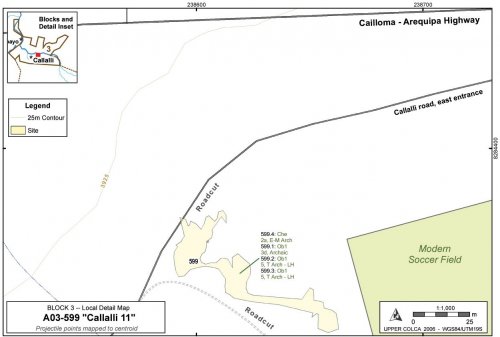

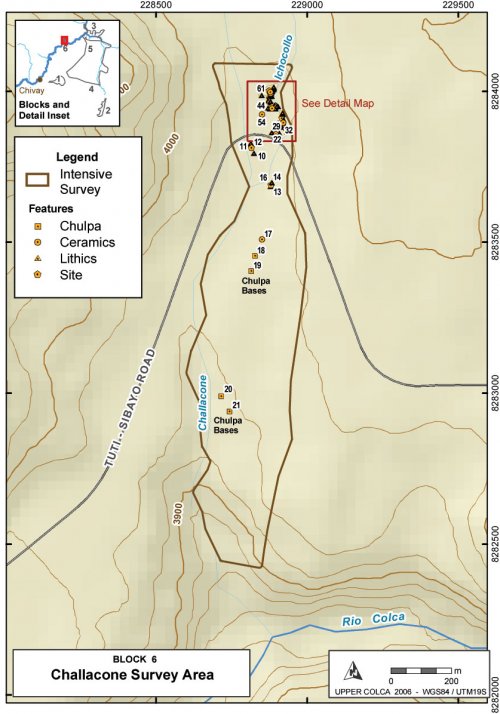

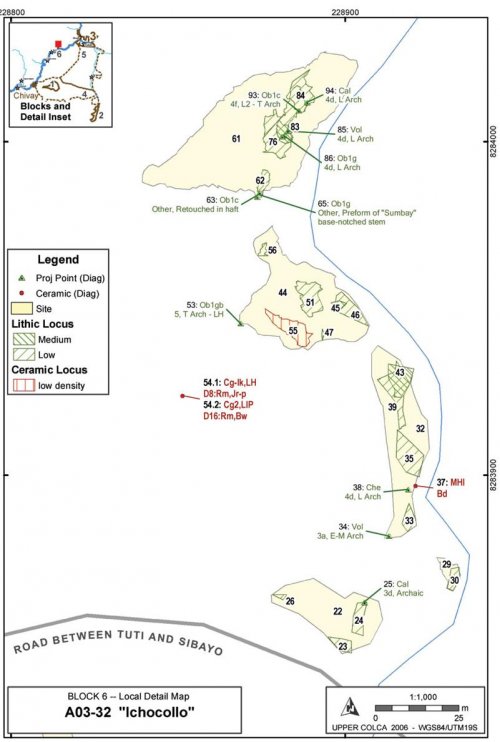

Projectile point counts shown in Table 6-34 include the Upper Valley areas of Block 3 and Block 6, and the counts also include projectile points from Kakapunku [a03-1000] that lay in the valley bottom segment of Block 5 on the perimeter of Block 3. The Upper Colca valley segment of the survey had relatively low numbers of Early, Middle, and Late Archaic Period occupation evidence as compared with other segments of the survey. As is evident from projectile point counts, only 26 of the 56 projectile points (46%) from this Upper Valley derive from the Archaic Foragers period, a 5700 year long time period.

Obsidian projectile points are well-represented throughout prehistory, although over half are Series 5 points from the Terminal Archaic and onwards. It is notable that obsidian is so well-represented in finished projectile point material types because evidence of production or maintenance in the form of obsidian flaking debris is far less common than chert in this area. Chert is found in the riverbeds in Block 3 and therefore it is the predominant local material. However, among projectile points in Block 3 obsidian predominates in all point styles except type 3D where obsidian is a close second. By count, obsidian is most frequent, but by weight obsidian points are smaller even if Series 5 point types are excluded.

Figure 6-23. Projectile Point weights and lengths (when complete) by material type for Block 3, Block 6 and adjacent valley areas of Block 5. Series 5 points are excluded and chalcedony is included with chert.

The projectile points made from the immediately-available chert material type are larger than points of either obsidian or fine-grained volcanics (andesite). The difference in mean weights was assessed using the Kruskal-Wallis non-parametric test because the distributions were not normally distributed. The Kruskal-Wallis test showed that the observed difference in means between the three groups is significant (c2= 8.235, .01 > p> .05).

Block 3 Archaic Foragers Archaic Settlement Pattern

Archaic Foragers sites in the B3 portion of the survey can be grouped into three categories of sites. For Archaic sites these categories generally correspond with socio-economic activity and lithic provisioning, as indicated by lithics observed during fieldwork and representative grab samples collected from the surface. The three categories of sites include: (1) large, sheltered base camps; (2) small logistical camps, and (3) chert provisioning and initial reduction locations along river banks. These three groups will be discussed, along with the specific characteristics of major sites in each group, and subsequently the isolated or uncategorized sites will be described.

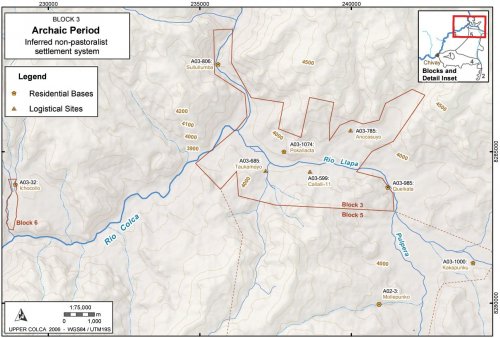

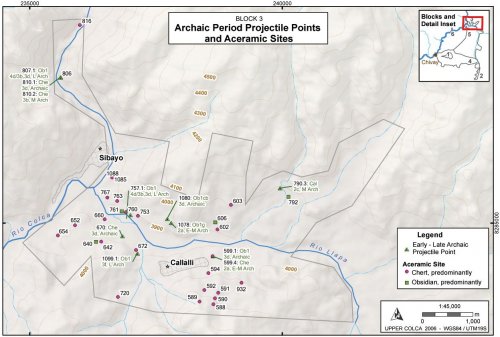

Figure 6-24. Archaic Period in Blocks 3, 6 and 5 (valley): Sites described in the text.

Figure 6-25. Block 3: Early, Middle, and Late Archaic projectile points and Aceramic sites.

A number of aceramic sites were difficult to differentiate from ceramic period sites and thus an comprehensive map, showing all of the potentially pre-pastoral sites, is depicted in Figure 6-25. Inclusively, this group includes most aceramic sites and locations with projectile points diagnostic to the Early, Middle, or Late Archaic Periods.

Site Type: Sheltered base camp

A03-1000 "Kakapunku" [A03-1000 - A03-1013]

The site of Kakapunku [A03-1000] (a.k.a. C'oponeta) is located on the south side of the Río Llapa on a north facing bluff just upstream of the confluence of the Río Llapa and the Río Pulpera. This site consists of three rock shelters spaced about 15m apart along the base of a 10m high irregular cliff band that lies approximately 30m up the hill and south of the high-water line on the Río Llapa. There is a colluvial ramp below the rock shelters and on a terrace below that ramp lie number of lithic loci and some ceramics. The rock shelters are generally north facing so that they are oriented to the mid-day sun and the shelters are warm and well-lit.

|

ArchID |

SiteID |

FileType |

Description |

Area (m2) |

|

1000 |

1000 |

Site_a |

"Kakapunku" |

3400.0 |

|

1004 |

1000 |

Lithic_a |

High Dens, ~70 Obs |

1771.3 |

|

1010 |

1000 |

Lithic_a |

High Dens, ~70 Obs |

76.7 |

|

1013 |

1000 |

Lithic_a |

Medium Dens, ~70 Obs |

148.6 |

Table 6-35. Loci in Kakapunku [A03-1000].

|

ArchID |

Description |

Height |

Depth |

Width |

Width Entrance |

|

A03-1001 |

Mortuary, looted. MNI=7 |

1.6 |

3.2 |

5.2 |

1.9 |

|

A03-1002 |

Domestic, warm rock shelter |

4 |

3.5 |

6 |

5.1 |

|

A03-1003 |

Mortuary, looted. MNI=14 |

1.6 |

~8 |

1.4 |

1 |

Table 6-36. Rock shelters at Kakapunku [A3-1000], dimensions in meters.

Figure 6-26. Site of Kakapunku [A03-1000].

A03-1001 -East rock shelter at Kakapunku

This is a looted mortuary context. The rock shelter is moderately difficult to access on a cliff face, and the entrance appears to have been formerly walled off. The original rock shelter height is difficult to determine because cist tombs in the floor of rock shelter have been excavated by looters. A number of complete crania and long-bones were present. The crania and long bones were examined in the field by Mirza del Castillo, a team member who is a physical anthropologist. From her in-field visual assessment she cautiously suggests that a number of the crania had female metric proportions, and that a number of the crania appeared to have hypoplasia of the bone marrow on the posterior edge of the parietal bones which is a possible indicator of anemia.

Figure 6-27. The entrance of A03-1001 with looted cist tomb visible inside the rock shelter.

A03-1002 - Center rock shelter at Kakapunku

This rock shelter is relatively shallow but other characteristics made it appear to be to be an inviting residential location for a small group of foragers or pastoralists. The shelter is dry inside the dripline, north facing, flat interior, defensible, a short distance from water, and immediately south of a terrace for open-air activities where loci a03-1004 through 1013 are located.

A03-1003 - West rock shelter at Kakapunku

This rock shelter is a lava tube sloping upwards into the cliff face. It appears to contain many disturbed interments. Undisturbed human remains perhaps exist here but they were not visible on the surface.

Discussion

Kakapunku is another case of a multicomponent site where discerning the Archaic component is difficult. Five projectile points were identified belonging to different Archaic Periods, and combined with the ceramics (described later), there is a some affiliation with virtually all time periods at this site.

|

ArchID |

Index |

Material Type |

Form |

Type |

Temporal |

|

1001 |

1 |

Obsidian |

Proj Point |

3a |

Early-Middle Archaic |

|

1002 |

1 |

Obsidian |

Proj Point |

2b |

Latter part of Middle Archaic |

|

1004 |

1 |

Obsidian |

Biface |

n/a |

|

|

1004 |

2 |

Obsidian |

Biface |

n/a |

|

|

1004 |

3 |

Obsidian |

Proj Point Broken |

5 |

Late |

|

1005 |

1 |

Volcanics |

Core |

n/a |

|

|

1007 |

1 |

Obsidian |

Proj Point |

3b |

Middle Archaic |

|

1008 |

1 |

Volcanics |

Proj Point |

4d |

Late Archaic |

|

1009 |

1 |

Obsidian |

Preform |

5a |

Late |

|

1010 |

1 |

Obsidian |

Proj Point Broken |

5d |

Late |

Table 6-37. Selected Lithics from Kakapunku [A03-1000].

On the terrace below the rock shelter [A03-1002] the largest concentration of artifacts were noted. Samples collected from the medium and high density lithic loci on the terrace are approximately 50% obsidian materials with the non-obsidian primarily consisting of aphanitic volcanic stone. The northern high density locus, A03-1010, is eroding down the cutbank caused by erosion and it is possible that this terrace was significantly larger but has been truncated by fluvial erosion of the terrace. In sum, Kakapunku appears to have served as a regular residential area with three relatively small rock shelters.

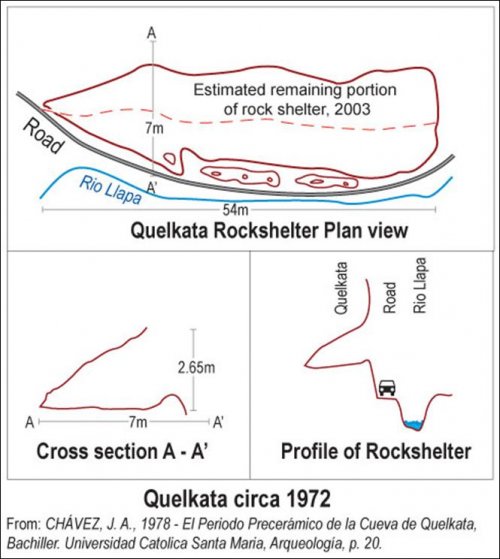

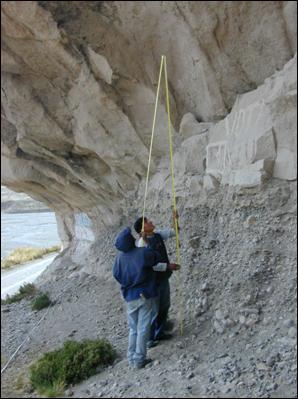

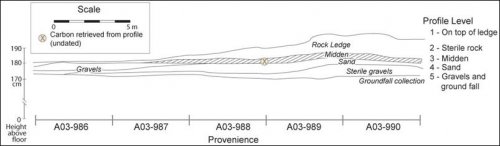

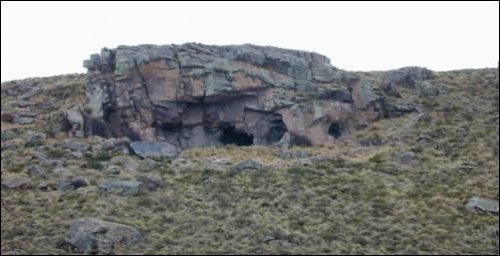

A03-985 "Quelkata"