Block 1 Obsidian procurement features

One of the biggest challenges of working at the Chivay source during the 2003 season was evaluating the evidence for the incentives that drove ancient people to excavate a quarry pit to acquire larger nodules of obsidian, and the evidence for who was responsible for the quarrying work. Presumably, the earliest visitors to the Chivay source had the first pick of the largest and most homogeneous nodules, but over the millennia the source would be relatively depleted as compared with the initial abundance during early human visitation sometime in the Early Holocene. A quarry pit [Q02-2] that was encountered in the south-east quarter of Maymeja is evidence that investing labor in excavating for obsidian was indeed worthwhile.

At some sources, for example in the upper reaches of the Alca source as described by Rademaker (2005, pers. comm.) large blocks of obsidian of variable quality are found littering the surface. At lower elevations at the Alca source, and closer to large settlements, small cavities and tunnels were excavated to retrieve obsidian (Jennings and Glascock 2002).

Q02-2 "Quarry Pit"

The upper area of Maymeja, as well as the eastern flanks of Cerro Hornillo, are blanketed with small fragments of obsidian that appear as lag gravels among the tephra soils of the area (Section 4.5.1). In particular, flows and large nodules of obsidian are exposed through erosion in some areas, which suggests that underneath the tephra are larger nodules, but one has to excavate for them. On the north side of Maymeja, in an area heavily eroded by glaciers, a flow of obsidian [Q02-1] was observed but it contained vertical, subparallel fractures and was generally not suitable for tool production.

At the same altitude as this natural flow, but 700m to the south and across several moraines is a quarry pit [Q02-2] located in an area where the ashy soil was particularly light-colored. Similar open-air obsidian quarries have been described in central Mexico as "doughnut quarries" (Healan 1997) and "extracción a cielo abierto" (Darras 1999: 80-84). See Section 7.4.1 for further details on this quarry pit.

The coordinates of the Q2-2 pit are 71.5355° S, 15.6423° W (WGS84 datum), and it lies at 4972 masl. Around this quarry pit many small obsidian nodules in a depression were encountered that were typically < 5cm in size, but a few were closer to 15cm on a side. There is a smaller mound of sandy soil and small fragments of obsidian inside the larger quarry pit, suggesting that someone has attempted to further excavate the quarry pit in the more recent past.

Figure 6-45. Testing at Quarry Pit Q02-2 with 1x1 test unit Q02-2u3. Snow remains in the pit.

During the 2003 field season a test unit was placed in the debris pile immediately downslope of this quarry pit. The quarry pit and the test unit results are described in more detail in Section 7.4.1 and a brief discussion of ancient quarrying methods can be found in Section 8.3.2.

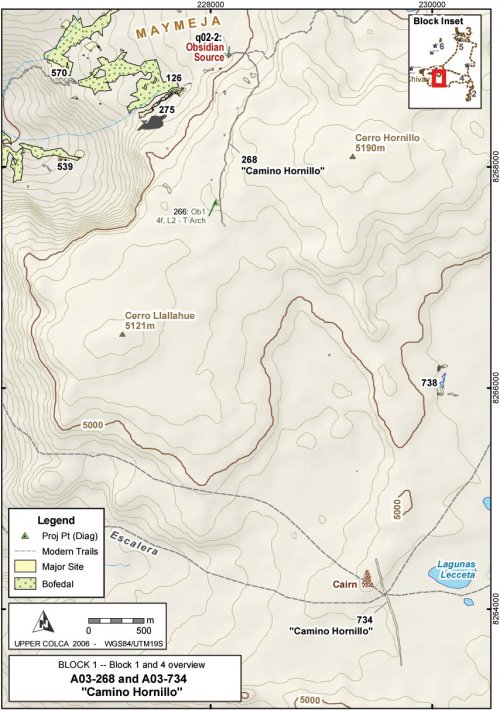

A03-268 "Camino Hornillo"

Departing from the quarry, a prehispanic road was identified that is 3-4m wide and is cleared of all but the largest rocks. This road [A03-268] departs the Maymeja area towards the south, following the route with the lowest gradient out of the volcanic depression, and avoiding difficult talus areas. As the road is defined by being swept free of rocks, the road is difficult to follow where it enters areas consisting only of sandy soil with no rocks to define its edges. In 2003 two sections of this road were mapped for a total of 3 km, and based on observations it can be described as of the " Cleared Road type: … systematically cleared of all stones or other debris" (Beck 1991: 75-76). While the soft pads of camelid feet negotiate rocky terrain with relative agility, loaded caravan animals generally travel on cleared roads and trails. Nielsen describes caravan routes in the open altiplano as "wide (4-10 m), straight, and free of vegetation, but lack[ing in] any improvement" (Nielsen 2000: 447). By these criteria, the route encountered at the Chivay source is relatively narrow, but it is roughly twice the width of a single-file path.

Figure 6-46. A03-269 and A03-734 "Camino Hornillo" and modern trail system.

No ceramics or architectural features were found in association with this road, and the only temporally diagnostic artifact identified was an obsidian type 4f projectile point diagnostic to the latter part of the Late Archaic and the Terminal Archaic. The construction of the swept road is being interpreted here as Terminal Archaic - Early Formative in age because it is associated with a workshop that contained radiocarbon dating to that time, and this date is further supported by the presence of the Terminal Archaic projectile point along the route.

At 4 km from the quarry pit, the southern segment [A03-768] of Camino Hornillo meets the Escalera route, a large trail that appears to have been a major thoroughfare for pack trains climbing steeply out of the Colca Valley to the puna and off towards the East-South-East (the direction of Lake Titicaca). A relatively large cairn or apachetastands on top of a boulder just northwest of this significant intersection, probably a guidepost marker in an otherwise open and featureless expanse.

|

Figure 6-47. Apacheta (cairn) close to junction of the Escalera route with Cerro Hornillo. |

While there were no artifacts associated with this cairn to facilitate dating its construction, the practice of contributing stones to cairns by passersby suggests that large cairn have some antiquity (Nielsen 2000: 447-448, 489). These features are associated with ritual activity in a variety of cultures worldwide including the North African Twareg (Rennell 1966 [1926]: 293), Tibetans (Trinkler 1931: 72), and other Himalayan highland groups (Valli and Summers 1994: 11). While cairns are abundant on an adjacent pass at Patapampa along the principal Arequipa highway to the Colca, those cairns have become a focus for tourist activity and many are the result of modern construction by passing tourists.

Today, the route of the modern Chivay - Arequipa highway has shifted traffic to Patapampa and around south side of Cerro Huarancante, and as a consequence these more ancient travel routes long used by pack animals, see little modern use except by local herders.

Interestingly, Camino Hornillo crosses the Escalera route and continues with the same width and definition in the direction of Nevado Huarancante to the south, as if the role of Camino Hornillo was more than simply a spur on the larger trail network in the direction of the Chivay obsidian source. Beyond the Lecceta-Escalera pass area, the Camino Hornillo [A03-734] begins climbing a hill and disappears again into sandy soil. Due to time constraints the 2003 field season team was not able continue following this road, but the route suggests that there was an objective in the southerly direction beyond the Escalera thoroughfare.

Figure 6-48. Camino Hornillo showing (a) A03-268 and (b) A03-734 segments. Photos were digitally modified to highlight the route in red.

The Quebrada Escalera route (in the southwest portion of Figure 6-46), which is now primarily a narrow footpath, seems to have had varying degrees of historical importance as access route in and out of the Colca. As reviewed in Section 3.2, the ethnographic accounts of caravans arriving into the Colca from the eastern puna are numerous (Browman 1990: 404,416-414;Casaverde Rojas 1977;Flores Ochoa 1968: 107-137). These caravans, by necessity, would have had to take one of the relatively steep routes that go to the north or the south of Nevado Huarancante. The route to the south of the mountain, which is the route taken by the modern highway to Arequipa (constructed in 1947 by Conscripcíon Vial), has steep pitches that would have presented obstacles to caravan transport as does the Quebrada Escalera route. Guillet (1992: 27-28) describes the historical importance of the construction of railroad station at Sumbay in Pampa de Cañagua, because with the railroad travel to the city of Arequipa by mule was reduced from being a one week journey to being a 2.5 day trip. One well-established route between Sumbay and Chivay passed through the Lecceta-Escalera area as it skirted north of Nevado Huarancante and descended Quebrada Escalera into the Colca. In sum, two faint segments are apparent of a road referred to here as "Camino Hornillo" that depart the quarry pit [q02-2] towards the south and arrive at the major travel route represented by the Escalera, but then the route continues southward in the direction of Huarancante. Further study of this road is needed.

Block 1 Reduction and projectile points in the Early Agropastoral period

Consumption patterns in the south central Andes indicate that projectile points are the most frequent artifact type for obsidian, a pattern that becomes particularly strong with Series 5 projectile point production sometime after the onset of the Terminal Archaic circa 3300 BCE An important question in this research is, therefore, "in what form was obsidian leaving the Maymeja zone during a particular time period?"

Part of this question is answered simply by looking at the 2003 projectile point inventory: obsidian Series 5 points are actually relatively scarce in the Maymeja area, and flakes that approach Series 5 projectiles in shape, are not especially common in the collections either (see Table 6-15, above). As will be suggested by the Maymeja excavation data in Section 7.4, distinct groupings of cores and flakes discarded at the workshop suggest that reduction was following a few discrete pathways that might indicate that two trajectories, both the flake-as-core and the flake directly to implement, reduction strategies were occurring at the Chivay source.