6.4.3. Block 3 - Callalli

An Early Agropastoral period occupation of the Block 3 area is evident from survey work, but it is less dense than was encountered for this time period in Block 2, and it is also more faint than the evidence from the Late Prehispanic in this the Block 3 area itself.

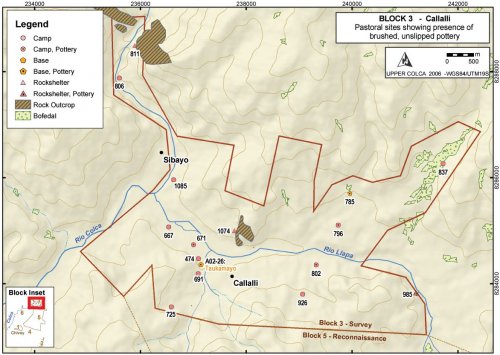

Figure 6-61. Early Agropastoralist settlement in Block 3.

The Early Agropastoral settlement in the Callalli area is difficult to isolate from later pastoral settlement, but the evidence that was encountered suggests that it was a distributed settlement pattern with similarities to the pastoral pattern observed elsewhere in the higher altitude portion study area. The criteria used to discern this settlement pattern were sites with pastoral attributes (grazing lands, water), and the potentially the presence of the unslipped Chiquero type ceramics considered Formative in the main Colca valley by Wernke (2003).

Occupations are generally small and diffuse, with rock shelters and river terraces providing the majority of the settlement locations. The rock shelter of Quelkata [Q03-985], described in the preceding Archaic Foragers - Block 3 section, had a substantial a-ceramic occupation. However the vast majority of the projectile points analyzed by Chavez (1978) appear to fall into Series 5 in the Klink and Aldenderfer (2005) typology, placing the occupation in the Terminal Archaic. Elsewhere in Block 3, several multicomponent sites were occupied during this time period, most notably Taukamayo [A02-26].

A02-26 "Taukamayo"

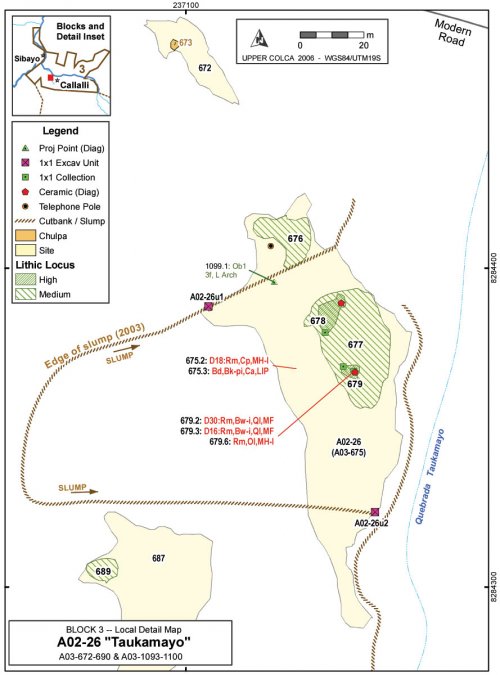

The multicomponent site of Taukamayo sits on a terrace above Quebrada Taukamayo just west of the modern town of Callalli. In the course of the 2003 survey the site was surface mapped as A03-675 in keeping with the 2003 survey methodology, but the official site number on the test excavation permit is A02-26. The site was tested with a 1x1m test unit and two partial units that produced dates circa cal AD650 (Section 7.6.1).

The site is located on a terrace above a tributary to the Río Llapa immediately upstream of the large confluence with the Río Colca. Located in a parcel owned by Noemi Ramos, who resides primarily in Arequipa, the site is located across Taukamayo creek from the modern village of Callalli. The town site of Callalli has Inka and possibly earlier components evident on the western edge of the town limits, but the occupation encountered at Taukamayo is earlier.

It is possible that Taukamayo was a peripheral site to the principal settlement at Callalli. Nielsen's (2000: 465-468, 490) ethnoarchaeological research on camelid caravans notes that when caravans stop overnight at settlements they will frequently camp in areas segregated from the principal settlement for two reasons. First, interference in the activities of residents, stampedes, and other forms of conflict can be avoided by remaining on the periphery of the settlement. Second, the agricultural fields can be better defended from caravan animals by camping a prudent distance from farm plots. In the modern trail system the principal route linking the Callalli area with the Chivay obsidian source and other high puna regions to the south climbs the Taukamayo drainage. Thus, Taukamayo may have represented a kind node in a larger transportation network because it is a relatively large site lying precisely in the area where the highland trail system joins the river network, but it is across the drainage from the settlement of Callalli.

Figure 6-62. Taukamayo [A02-26], a multicomponent site partially destroyed by a landslide.

Figure 6-63. Overview of Taukamayo [A02-26] on slump along base of hillside. Grey box shows area detailed in Figure 6-64, below.

Figure 6-64. Taukamayo [A02-26] detail showing two test units locations on cutbank margins of the creep area. Excavators are visible on right-side at A02-26u1 and provide scale for photo.

Ceramics

The multicomponent nature of this site is most evident from the spatial and temporal variety of pottery styles observed here. This site contained the only pottery diagnostic to the Titicaca Basin Formative, and it also has a sherd from a Titicaca Basin LIP beaker. Tiwanaku sherds, however, are conspicuously absent as they are elsewhere in the valley contrasting with regional obsidian distributions.

|

Period |

Estilo |

Beaker |

Bowl |

Olla |

Neckless Olla |

Plate |

Cup |

Unknown |

Total |

|

LH |

Collagua-Inka |

2 |

1 |

3 |

|||||

|

LIP-LH |

Collagua |

1 |

1 |

||||||

|

LIP |

Colla |

1 |

1 |

||||||

|

MH |

Local MH |

1 |

1 |

2 |

|||||

|

F-MH |

Chiquero-like |

2 |

1 |

6 |

7 |

1 |

8 |

25 |

|

|

MF |

Qaluyu-like |

2 |

2 |

||||||

|

Total |

6 |

3 |

7 |

7 |

1 |

2 |

8 |

34 |

Table 6-5. All ceramics from Taukamayo [A02-26] and vicinity.

Evidence from ceramics reveal that while the site has components from all ceramics-using periods, the strongest evidence is from the earlier periods, particularly from the unslipped, brushed ware that has similarities to Chiquero style from the main Colca valley. These Chiquero-like sherds at Taukamayo are notable because this style of sherd is abundant at this site, and while this style was widespread in Block 2 the 2003 survey data shows that Taukamayo is the only location in Block 3 where Chiquero style sherds were encountered.

Surface collection in the slump debris at the site also revealed several sherds that appear to belong to Titicaca Basin styles, representing one of the few pieces of possible evidence of reciprocation for the quantities of Chivay obsidian that have been found in the Titicaca Basin. These Titicaca Basin styles include two sherds with similarities to the Middle Formative north Titicaca Basin style Qaluyu or early Pukara.

Figure 6-65. Non-local incised and stamped pottery from Taukamayo [A02-26], in the 2003 provenience these are A03-679.2 and A03-679.3.

Furthermore, a Colla sherd from the Titicaca Basin LIP was found here. The relatively high density of non-local ceramics from Taukamayo supports the idea that Taukamayo was a camp for non-local passersby, and perhaps caravan moving through the upper Colca valley.

Condition of Site

The site was partially destroyed by a broad slumping of the hillside above the site. Callalli residents (Ramos, Ordóñez, Windischhofer) have indicated that the creeping displacement began during the rainy season in early 2001.. Down-cutting in the stream bed of the adjacent Quebrada Taukamayo may have contributed to the recent creep. A historically large El Niño - Southern Oscillation occurred in the years 1997-1998, and a smaller one occurred in 2002-2003, therefore the slumping was not immediately attributable to the unusually heavy ENSO rainfall. Furthermore, a 2.5 m deep trench diverting water from the slope above Callalli was cut in the recent past, and this trench diverts water into the Quebrada Taukamayo watershed. The increased water volume in the quebrada beginning after the 1997-1998 ENSO and with additional water from the Callalli diversion trench, is perhaps contributing to a significant down-cutting of the stream bed which leads to a greater overall gradient of the slope and greater probability of sliding.

In the debris pile at the base of this landslide, ceramics from a variety of time periods were encountered, revealing the multicomponent nature of the settlement. While the landslide has destroyed much of the site, and threatens to destroy more area immediately north and south of the current slide zone, the creep has presented a few opportunities for archaeological observation as well. First, in the debris pile at the base of the slump one is able to observe ceramics from throughout the temporal sequence at the site. Second, in the cut on the north and south edges of the landslide, places where the cut varies between 50cm and 200cm in height, the 2003 survey team was able to observe lenses containing ash, bone, lithics, and pottery, permitting a relatively targeted testing of this deposit.

Discussion

It is immediately apparent that Taukamayo is an unusual site in the Block 3 area. The variety of ceramics and the diversity of lithic material types suggest that the occupants of the site participated in the circulation of goods on a larger geographical scale than did other sites in the region. Furthermore, while bifacially flaked obsidian implements were not uncommon in Block 3, these artifacts appeared to be relatively highly curated. At Taukamayo, reduction evidence from unmodified flakes and cores of obsidian was widespread.

The diversity of ceramic types observed at this site, and the potential for encountering ceramics from various stratigraphic levels in the mixed debris of the slump deposit, was significant. Non-local materials were encountered in styles belonging to the Titicaca Basin dating to the Middle Formative and the Late Intermediate Period, however in the broad sample provided by the Taukamayo landslide debris there was a notable lack of diagnostic ceramics from the time periods featuring the most political integration in the Titicaca Basin: the Late Formative polities and the Tiwanaku period.

Lithics

The most notable feature of Taukamayo was the relatively high density of obsidian as compared with other areas of Block 3. It appears that obsidian reduction occurred here on a number of occasions and due to the landslide, obsidian flakes appear in many parts of the slide deposition pile.

|

Taukamayo Cores - Surface |

Entire Block 3 Surface Collection |

|||||||

|

Material |

No. |

m Cortex |

mWt |

sWt |

No. |

m Cortex |

mWt |

sWt |

|

Obsidian |

10 |

25 |

14.31 |

7.8 |

17 |

5.0 |

23.2 |

13.1 |

|

Volcanics |

- |

- |

- |

- |

2 |

7.5 |

87.7 |

42.6 |

|

Chalcedony |

- |

- |

- |

- |

4 |

16.7 |

47.5 |

18.1 |

|

Chert |

1 |

0 |

34.4 |

- |

18 |

32.1 |

57.17 |

33.8 |

|

Total |

12 |

32.1 |

48.4 |

29.0 |

41 |

21.6 |

43.6 |

31.3 |

Table 6-53. Cores from the surface of Taukamayo as compared with the entire Block 3 surface collection.

Obsidian cores (all Ob1) were relatively abundant at Taukamayo but they were not exceptionally common. Nodules of black and tan colored chert were observed in the creek bed at Taukamayo and the material was being flaked elsewhere on terraces adjacent to the creek, but curiously only one core of this chert was found at Taukamayo. The distribution of obsidian material at the site suggests that a range of reduction stages on obsidian were occurring in this location and comparably less of the local chert or quartzite material was in use.

|

Ob1 |

Ob2 |

Volcanics |

Chalcedony |

Chert |

Quartzite |

Total |

|

|

Flakes |

138 |

199 |

53 |

25 |

181 |

79 |

675 |

|

Cores |

11 |

8 |

- |

2 |

4 |

1 |

26 |

|

Points & Tools |

22 |

15 |

1 |

- |

1 |

- |

40 |

|

Hoes |

- |

- |

16 |

- |

- |

- |

16 |

|

Total |

171 |

222 |

70 |

27 |

186 |

80 |

757 |

Table 6-54. Counts of lithics from surface collection at Taukamayo [A02-26].

This table shows that counts of obsidian are relatively high at Taukamayo. These counts should not be compared directly with other sites in Block 3 because these analysis results reflect two unusual aspects of Taukamayo. First, the high counts at this site are, in part, due the visibility of lithics in the debris from the landslide. Second, a detailed lithics analysis was conducted on the excavated materials from A02-26u1, as well as on surface materials from this site, and these high counts reflect this detailed analysis.

Chert and quartzite are immediately available in this area, and yet these material types are the minority in representation in flaked stone artifacts at the site. Secondly, Ob2 obsidian was relatively common at Taukamayo. As compared with the Block 2 site of Pausa (see Table 6-51 in Block 2 discussion) where obsidian use is primarily (87%) Ob1 material, at Block 3 Taukamayo there appears to be less concern for the clarity of the material or the presence of heterogeneities because 57% of the obsidian artifacts are Ob2 material. In fact, Taukamayo contains the highest proportion of bifacially flaked tools made from Ob2 material from the entire survey area. Notably, however, these were primarily bifaces not points, as only two of the artifacts made from Ob2 obsidian were projectile points.

Figure 6-66. Sixteen large andesite hoes were found at Taukamayo [A02-26].

Finally, this site contained an exceptional collection of sixteen large, broken andesite hoes. The hoes varied considerably in size, and it is difficult to assess the original, unbroken size of the items. The hoes ranged in weight from 112g to one as large as 1189g (shown in Figure 6-66, right), with a high variance. All showed signs of intial shaping with percussion flaking as well as flake scars from use. The mean weight was 512g, but with a standard deviation of 483.7.

These hoes had bifacial flaking on the working edge, and most showed polish from use, but no hafting wear was observed under visual inspection. The source of the andesite has not been determined, but if the source lies somewhere distant it is possible that, as with obsidian, Taukamayo contained a high percentage of non-local lithic materials that contrasts with neighboring sites in the area (see lithic analysis data reported in Section 7.6.1).