6.5. Survey Results: Late Prehispanic Period (AD400 - AD1532)

This temporal period includes the Tiwanaku Period in the Titicaca Basin (AD400) through the Inka Period (AD1532), a time when geographical distributions of Chivay obsidian are strongly influenced by pan-regional political and economic forces. Following anthropological models, it is among ranked or stratified societies that the procurement and redistribution of scarce raw materials is expected to occur as part of elite political strategy (Earle 1991;Renfrew 1975). If obsidian was a sought-after commodity that was controlled and redistributed by among complex polities one might expect restricted access or some other sign of control by the dominant state power at or near the obsidian source. The use of irregularly distributed raw materials, like obsidian, among complex polities may also involve either reciprocation or direct exploitation by agents of those polities, both processes that may leave evidence in the vicinity of the obsidian source.

Archaeological horizons during the Late Prehispanic period in the south-central Andes are demonstrated by stylistic commonalities that include pottery, architecture, and portable goods that were distributed within regional polities. These stylistic similarities are distinctive, well-studied, and often diagnostic to time period. Very little evidence was encountered in the course of this research of obsidian procurement by non-local parties, despite the abundant evidence of Chivay obsidian consumption in the larger region and sometimes in civic/ceremonial core of these regional polities. Nevertheless, the procurement and initial production activities of obsidian under the larger regional influences of the Late Prehispanic period may provide insights into the economy in which obsidian was circulated. When the larger economy was restructured by regional polities, the transformation that occurs in the circulation of goods like obsidian can demonstrate the differences between the older established economic patterns and the establishment of new patterns under the authority of a regional polity.

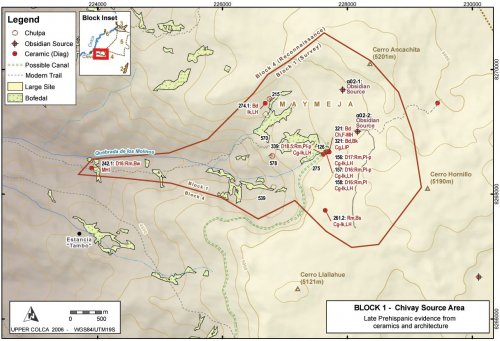

6.5.1. Block 1 - Source

The 2003 Upper Colca project evidence from diagnostic artifacts indicate that Late Prehispanic activity in the obsidian source area principally took the form of pastoral activities, construction of mortuary architecture, and possible water control projects. Evidence from the Late Prehispanic in this area depends largely on the presence of diagnostic ceramics and architecture, but if the example provided by modern pastoralists in the area may serve as an indicator, architecture was likely akin to the traditional herder's shelter, and vessels were probably non-diagnostic utilitarian cooking vessels. A few utilitarian vessel sherds were observed in the Block 1 area, but the overall presence of pottery was relatively low. Another pattern that can be safely extrapolated into prehistory is that the residents of Maymeja were probably not wasteful with the pottery that they had transported up to the grazing area, because pottery is relatively scarce in this area. Thus, the ability of archaeologists to perceive activities during the period termed "Late Prehispanic" depends to some degree on recovering diagnostic features that differ from the well-established herder pattern that had predominated in the Maymeja area for probably 5000 years. Other good evidence of Late Prehispanic procurement and processing by local groups would come from consumption patterns observable in adjacent settlements during that time period, principally in Blocks 2 and 3 of the 2003 survey.

From the evidence of Chivay obsidian distributions, the quarry and the associated workshop may be expected to have continued use through the Tiwanaku period or LIP, and then it would decline in use during the Inka and the Colonial period. In the Colonial period with the widespread availability of metals and bottle glass, obsidian use was largely abandoned, except for minor applications by local pastoralists. Therefore, during the Hispanic period the quarry pit may have been abandoned and the quarry and workshop features would perhaps be covered by soil accumulation and ash deposits from nearby volcanoes after more than 500 years with little use.

As will be presented below, the 2003 survey found no diagnostic evidence of Tiwanaku, and no Colla (non-local LIP) materials in the quarry area. Limited Inka and Collagua-Inka pottery were encountered, and these Late Horizon ceramic distributions appear to have been primarily related to mortuary features and to the focus on the water and the grazing opportunities in the Maymeja area.

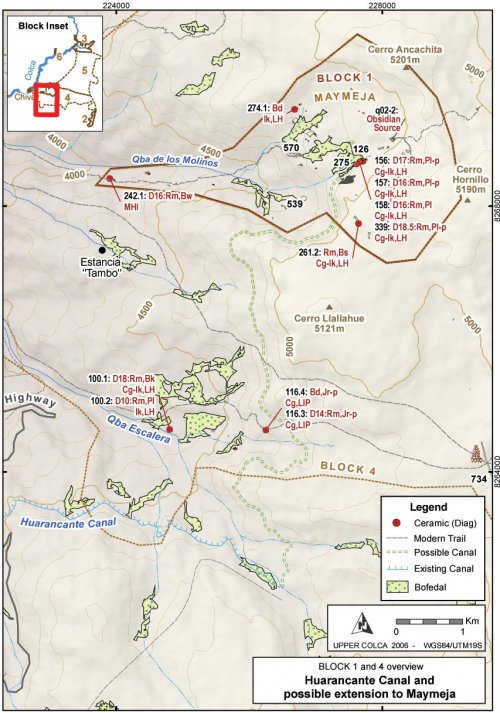

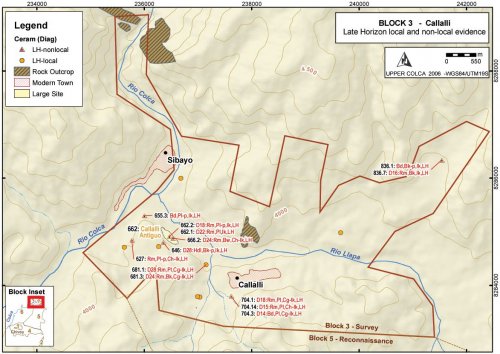

Figure 6-67. Block 1 Late Prehispanic features.

Pastoral activities

Grazing activities appear to have persisted during the Late Prehispanic in Block 1 as they did during the Early Agropastoralist period. Low densities of non-diagnostic sherds from utilitarian wares are found in association with colonial and modern sherds near the estancia in Maymeja A03-570. Pottery is otherwise relatively scarce in the Maymeja area. It is notable that no diagnostic MH, LIP, or LH sherds were found in association with the estancia at A03-570, or at other pastoral occupations in Maymeja, except for the A03-126 workshop area. One can also expect the later occupants of Maymeja to have continued to make use of the "Camino Hornillo" [A03-268] route leading to the quarry pit from the Escalera thoroughfare. However, if Late Prehispanic peoples did make use of this route, they left virtually no ceramics associated with it that would indicate that the quarry pit road was a regularly used feature.

A03-275 "Maymeja 5"

Just southwest of the area of the obsidian workshop, on the south perimeter of Maymeja, an extensive construction area (1 Ha) was encountered on the rocky slope along the edge of the bofedal that was generally terraced although heavily eroded. This area is shown in more detail on the map in Figure 6-54.

Figure 6-68. Three levels of terracing in [A03-275] below glacier polished rhyolite flow. Yellow tape shows 1m.

The construction along the margins of the bofedal was curiously devoid of ceramics, as were the other terraces immediately adjacent to the A03-126 Maymeja workshop. A light scatter of obsidian flakes is found throughout the terraced area, however, and obsidian flakes are concentrated along the base of the slope although these concentrations probably reflect downslope movement of artifacts. In this sector, on the south-west edge of the bofedal, several Late Horizon "Collagua-Inka" plates were encountered, and it is possible that this entire sector was constructed at a later time. The corner of a structure with a possible niche that appears to be built using the Inka-influenced cut-stone masonry technique was found 70m southwest of the obsidian workshop [A03-126] inside the larger terraced site area [A03-275]. Unfortunately, the remaining sides of this structure are too eroded to permit an estimate of the structure size, or to discern if it was a residential or mortuary construction. A pattern discussed by Wernke (2003) in the Colca valley was for circular residential structures to be dominant among pastoral settlements above 3900m. Given this architectural pattern, the structure at A03-339 is perhaps a square chulparather than a residential structure.

Figure 6-69. (a) Cutstone masonry [A03-339] from site A03-275 close to the workshop area at the Chivay obsidian source. Yellow tape shows 50cm. (b) Rim sherds from an 18cm diameter Inka-Collagua plate were found adjacent to this corner.

The presence of diagnostic Late Horizon materials in the obsidian source area was somewhat unexpected because during the Late Horizon the regional distribution of Chivay obsidian was relatively restricted in comparison with any time period since the Terminal Archaic. It is possible that the Late Horizon occupation in this area, particularly the painted plates, result from ritual functions associated with the abundant spring that irrigates the bofedal in the southern of Maymeja area, and that spring emerges very close to this location. However, if the structure [A03-339] is a looted Late Horizon chulpa, then the plate could have been one of the grave goods.

A03-240 "Molinos 1"

The only local Middle Horizon evidence from Block 1 close to the Chivay source comes from a pastoral area part of the way up the Quebrada de los Molinos climbing up from Chivay, 350 vertical meters above the town. This site is found adjacent to several large breccia boulders near a bofedal where the trail climbing from Chivay levels out after a steep pitch. A partially eroded rim sherd [A03-242.1] was found here that is diagnostic to the local Middle Horizon style. The sherd is made of burnished brown paste and with traces of paint on the rim, but the rim was too small to take a measure of the vessel diameter.

Mortuary features

Several chulpaswere identified in the Maymeja portion of Block 1, the locations of these features is shown on Figure 6-67.

A03-215 "Saylluta 1" appears to be a relatively large chulpa(2m in diameter). A mortuary function for this structure is suggested by the doorway which is only 70 cm high. No diagnostic materials were found. The base of a square structure was located just to the east that is possibly an old corral or a shelter, but it appears to be too large to be a roofed space.

A03-274 is a small crevice west of A03-201 with remnants of a wall inside and several small bones that appear to have been animal bones. A diagnostic Inka rim sherd of non-local design [A03-274.1] was found here.

A03-578 is circular chulpamade with double-walled construction, but without mortar. The chulpameasures approximately 2m in diameter. A site consisting of a light scatter of obsidian [A03-575] surrounds the chulpaand extends out onto a large promontory overlooking the Quebrada de los Molinos and the access to Maymeja from the trail climbing up from Chivay. There was also a medium density lithic locus here [A03-576] consisting primarily of flakes in tertiary stages of reduction (0-50% dorsal cortex). This site conforms to the pattern of lithic reduction atop the bluff on the western edge of Maymeja with very high observation potential. Visibility/exposure at this site is 39 by the visibility index, while the mean for sites in Block 1 is 18.5. This high visibility reduction pattern is discussed in Section 8.3.3.

In addition, the corner of the eroded structure at A03-339, described above, is perhaps a LH square chulpa(Figure 6-69).

Possible Late Prehispanic canal route

As agricultural intensification and terrace construction accelerated during Late Prehispanic times, the volume of water entering canal systems from the high altitude headwaters would have become increasingly important to the farmers below. The Huarancante canal system that irrigates the southern half of the Colca valley has been discussed in more detail elsewhere (Brooks 1998: 203-213;Wernke 2003: 235-246). This canal irrigates some of the most productive farm land in the main Colca valley, including the area around Yanque, the dominant community during the LIP and LH. Any additional water contributed into the Huarancante canal system would have been of great utility downstream.

While no glaciers are found in the Maymeja area and the precise date of deglaciation of Cerro Ancachita and Hornillo are not known, the spring that irrigates the southern half of Maymeja has a relatively high volume of flow. This flow is particularly notable in this porous volcanic landscape, where much of the surface water disappears underground. The substantial volume of water that descends from here to Chivay was sufficient to justify the construction of a mill during colonial times (the apparent namesake of Quebrada de los Molinos). Today, this water powers a small hydroelectricity plant for Chivay.

According to Sr. Mamami (2005, pers. comm.), the owner of "Tambo", a rich estancia between Chivay and Cerro Hornillo, a canal existed that connected Maymeja with Huarancante in the past and it traversed high above eastern edge of his land. Upon further discussion with S. Wernke (2005, pers. comm.), the significance of a possible extension to the modern Huarancante canal is explored here, as this extension would have been an important asset had it connected the abundant perennial spring in Maymeja to the Huarancante canal.

A possible route using contours derived from the ASTER 30m topographic DEM layer is presented here. Following Brooks' (1998: 203) estimate of 1° or less downslope for the canal, the canal is extended up from the point at which the existing canal departs from Quebrada Huanta Occo at 4745 masl on the north slopes of Nevado Huarancante. The contour distance to the Maymeja bofedal is approximately 10.5 km, which, at a 1° slope, would require a vertical change of 183m, indicating that the canal would have had to begin at around 4928 masl. The altitude of the Maymeja workshop in site A03-126 is 4902m, therefore when extrapolated over more than 10km the gradient potential exists for such a canal, but it would have required losing very little altitude across difficult terrain. No specific cliff bands block the construction of such a canal, but a steep lava cliff passes immediately above the canal route and the slopes below this loose cliff consist of an incline of sand and talus at approximately 45°. These features would have presented a difficult obstacle to canal construction.

Under Inka rule, the Collagua extended their agricultural production through projects such as canal expansion, and the construction of such a canal would serve to explain, in part, the predominance of Late Horizon Collagua-Inka ceramics over LIP Collagua ceramics in the Maymeja area. Unfortunately, due to fieldwork time constraints, the Upper Colca survey project was not been able to conduct a pedestrian survey along this potential canal route. The route contours around an extremely high colluvation zone below the lava outcrops of Cerro Llalluhue, and a canal in this area would have required significant maintenance.

The possible canal route shown on Figure 6-67 and Figure 6-70 is 11 km long and drops from 4905 to 4745 masl at a gradient of 0.83°. No features definitively related to canal construction were observed, but further fieldwork could confirm Sr. Mamani's account. Another possibility is that the Inka-Collagua presence in the Maymeja area results from a work-in-progress where feasibility study measurements and initial work were perhaps underway for the construction such a canal in the 16thcentury when the Spanish arrived. A scenario such as this would have left somewhat ambiguous evidence in the Maymeja area.

Figure 6-70. Blocks 1 and 4 overview showing possible route of Late Prehispanic canal.

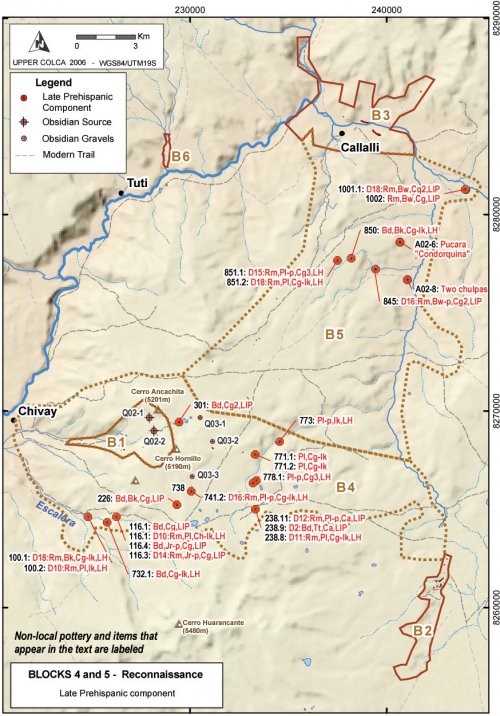

Block 4 and 5 Reconnaissance Area

During the Middle Horizon, LIP and Late Horizon in the high altitude reconnaissance area near the Chivay source, several clusters of sites were observed that testify to the variety of lands used by pastoralists in this period. During the 2003 survey non-local Inka ceramics were encountered even in small, distributed pastoral sites, a higher frequency of use of obsidian with heterogeneities (Ob2), and a spatially distributed occupation pattern. These distributions perhaps reflect the growing herd sizes in the Collagua domain during the Late Prehispanic, and the need to exploit the resources in the puna as they become seasonally available.

Figure 6-71. Blocks 4 and 5 Reconnaissance - Late Prehispanic component.

An example of this distributed occupation pattern was apparent in the arid area on the south-east flanks Cerro Hornillo. Surveying across this arid area, the 2003 survey team encountered a settlement close to two ponds A03-738 "Lecceta 1" consisting of two small rock shelters and open air sites containing LIP and LH ceramics. The site includes a light scatter of obsidian flakes over the larger region, and two sectors with medium and high density obsidian scatters. The interesting thing about this site is the high incidence of use of Ob2 obsidian.

Between 500m and 1000m north of this settlement surveyors encountered surface obsidian lag gravels eroding from the base of the south-east flank of Hornillo in a formation that appears to represent a secondary obsidian quarry area. In fact, on further investigation of the source materials, it was noted that much of the obsidian on this side of Hornillo had heterogeneities (Ob2) consisting of <1 mm air bubbles trapped in the glass, as well as what appear to be ash particles. The nodules in this area were as large as 15cm long, but the typical large nodule for the area was only < 8 cm on a side. It seemed like the larger nodules had more Ob2 heterogeneities, as if perhaps there had been a preferential collection of large Ob1 nodules from this area.

The site of Lecceta 1 [A03-738] had unusually high levels of use of Ob2 obsidian. The Ob2 material was being knapped more extensively than anywhere else in the survey area.

|

Form |

Ob1 - homogeneous |

Ob2 - heterogeneous |

||||||

|

At site A03-738 |

Project surface collection |

At site A03-738 |

Project surface collection |

|||||

|

Tools |

2 |

100.0 |

290 |

92.7 |

- |

- |

23 |

7.3 |

|

Cores |

17 |

70.8 |

201 |

84.5 |

7 |

29.2 |

37 |

15.5 |

|

Flakes |

17 |

60.7 |

201 |

84.5 |

11 |

39.3 |

101 |

21.4 |

|

Total |

36 |

66.7 |

861 |

84.2 |

18 |

33.3 |

161 |

15.8 |

Table 6-55. Ob1 and Ob2 obsidian use at A03-738 "Lecceta 1" compared with entire project.

While there were more Ob1 cores, flakes, and tools collected at A03-738, there was a fair amount of reduction was occurring on the Ob2 material that was available near this camp. In particular, Ob2 cores and flakes are used at a much higher percentage in this site on than on average for the project on the whole. Given the Late Horizon evidence from this site, these data could be interpreted as supporting the notion that during the Late Prehispanic the acquisition of "high quality" obsidian, represented by Ob1 material, was deprioritized because obsidian was primarily used for the basic pastoral functions of butchering and shearing.

6.5.2. Block 2 - San Bartolomé

The Late Prehispanic occupation of the high puna area of San Bartolomé shows a continuation of earlier pastoral uses of the Block 2 grazing lands, but the ceramic assemblage reveals the strong links between this area and the main Colca valley. The modern political structure of Block 2 links this area to the town of Yanque in the Colca valley. Political hierarchy related to the structure of aylluorganization in the Colca valley was reflected in the estanciasand anexosof the herding areas such as Block 2 (Benavides 1989;Wernke 2003: 359-368).

Despite the ascendancy of Chivay in the early twentieth century (Guillet 1992: 27-29), the regional dominance of Yanque in the Late Prehispanic and colonial period is reflected in the large number of Collagua anexos, such as the communities of Chalhuanca, Pulpera, and the estancias that fall within the Upper Colca Project Block 2 survey area. These anexosall belong to Yanque, despite being geographically closer to Chivay. Straight line distance from the site of Pausa [A03-39] in Block 2 across to Chivay is 22 km, while the distance to Yanque is 28 km. When traveling from Pulpera one would walk through Chivay to get to Yanque most directly. Residents in these Collagua anexostravel to Yanque to vote in elections; and, fittingly, the family name of virtually everyone encountered in Block 2 was "Callagua". The ties between residents of Block 2 and the Colca valley appear strong in the ethnohistoric and modern records, but the archaeological evidence from Block 2 reveals that this area was also a place of contact with Titicaca Basin communities. The ceramic evidence is strong, at least, for Titicaca Basin interaction during the Late Intermediate and Late Horizon.

Discussion

The Late Prehispanic occupation of the Block 2 area appears to have been oriented towards maintaining herds in this grazing area. Small quantities of non-local pottery were encountered here, but the overwhelming majority of the styles demonstrate the close connection between this area and the main Colca Valley.

Late Horizon

The Late Horizon evidence from the San Bartolomé area comes primarily from sherds of the Inka-influenced local ceramic style described as Collagua-Inka (Wernke 2003). A number of Collagua-Inka plates and beakers were found in Block 2, and approximately half of them were painted. A number of painted, non-local Inka plates were found in this area as well, particularly in the northern Chiripascapa area. Ethnohistoric sources document the vast herds of camelids tended by the Collagua (Crespo 1977;Wernke 2003: 83-84). From his survey work, Wernke (2003: 184) reports a distinct expansion of herding in the LH where "…nine of the 16 Late Horizon herding settlements that lack LIP components are pastoralist settlements located in the puna". Wernke also reports finding a small number of LH sherds with similarities to the Chucuito (Late Horizon Titicaca Basin) style in the course of his survey, and these sherds were observed in herder settlements in the puna on both the north and south sides of the main Colca valley.

In the Block 2 area a relatively consistent occupation was encountered in the 2003 Upper Colca survey that includes both LIP and the LH settlement. There is some suggestion of slightly lower occupation during the LH, but this may be the result of concentration of settlement into a fewer but larger pastoral bases.

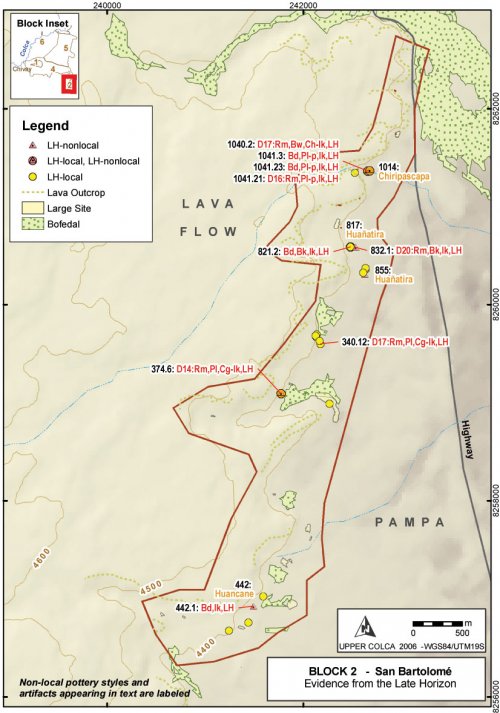

Figure6-77. Block 2 diagnostic artifacts from the Late Horizon.

Two LH sherds from the 2003 survey were of the Titicaca Basin Late Horizon Chucuito style and they were both observed in the Block 2 survey area. The presence of only two Titicaca Basin sherds is a notable a reduction from the LIP when 14 Colla sherds were encountered in this area. The LH is a much shorter time period than the LIP, but nevertheless the reduction is notable and perhaps reflects a deliberate effort by the Inka to regionally isolate Aymara polities and intercede in Colla and Collagua economies.

Middle Horizon and Late Intermediate Period

The evidence for Middle Horizon occupation in the San Bartolomé area is confined to the northern part of Block 2. A number of beaker rims in local Middle Horizon styles were found in this area in association with pastoral features. A sherd of undetermined stylistic origin was found [A03-1056.1] with geometric elements that suggest a Middle Horizon or perhaps LIP date (B. Bauer, 2004 pers. comm; K. Schreiber, 2004 pers. comm.).

|

Figure 6-72. Non-local sherd with geometric elements akin to Middle Horizon or LIP styles [A03-1056.1]. |

It is not evident whether the pattern of Middle Horizon settlement in the north part of Block 2 predominantly reflects cultural relationships, environmental conditions, or some combination of the two. Culturally, the settlement in the northern parts of Block 2, in particular the Huañatira area, may have maintained close links with the Colca valley and therefore the pottery better reflects styles that were documented by Wernke (2003) in his seriation of pottery in main Colca valley.

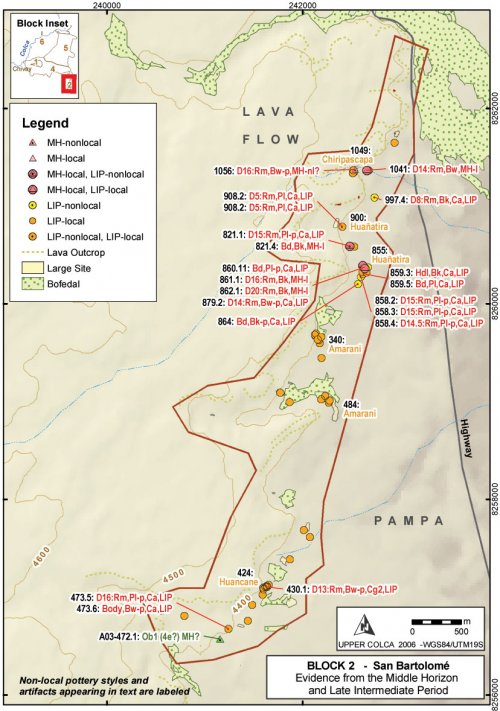

Figure 6-73. Block 2 diagnostic artifacts from the Middle Horizon and Late Intermediate Period.

From an ecological perspective, the bofedal along the northern part of Block 2 has significantly greater dry season water flow than the smaller bofedales in the southern parts of the survey block, and perhaps settlement was concentrated in the northern area of Block 2 during the Middle Horizon in order to exploit the large bofedal that lies to the north-east. During the October dry season, when the Upper Colca Project surveyed in this area, grazing was only occurring at the bofedales that are depicted on Figure 6-73.

The local Late Intermediate period evidence in this region consists primarily of sherds from Collagua-1 and Collagua-2 style bowls (Wernke 2003), some of which were painted. Significantly a number of sherds from Colla style beakers and plates from the Titicaca Basin were encountered, some of which were painted, that belong to the "Altiplano" LIP pottery tradition. The sherds from painted plates observed here belong to a style that is also found in the mid-sierra of Moquegua (Stanish 2004, pers. comm.).

These beakers and plates artifacts, the proveniences of which are labeled on Figure 6-70, are part of a larger suite of shared traits between the Collagua of the Colca and the Colla of Lake Titicaca. These traits include the construction of fortified pukaras, mortuary architecture, cranial modification, and the Aymara language (Section 3.5.3). Despite this apparent affinity, obsidian is not abundant on the Late Intermediate sites of northern Late Titicaca Basin(Arkush 2005: 247, 709-711).

A03-855 "Huañatira 2"

This site shows the pattern of reoccupation of these enclosed raised corrals as were discussed above with the Early Agropastoralist occupation of A02-39 "Pausa 1", and it is also adjacent to a Archaic Foragers occupation described above in the Archaic Period discussion of A03-900 "Huañatira". This site contains components from a variety of time periods, and it demonstrates the redundancy, the non-contemporaneous occupation, and the shallow refuse disposal that were encountered in most pastoral sites (Nielsen 2000: 480-483).

Figure 6-74. Huañatira [A03-855]. Corrals, structures, and artifacts scatters wrap around the base of the lava escarpment. A small figure is visible on the right edge for scale.

|

Time Period |

Style |

No. |

% of Column |

|

Non-local LH |

Chucuito-Inka |

1 |

1.1 |

|

Inka |

3 |

3.2 |

|

|

Local LH |

Collagua-3 |

11 |

11.8 |

|

Collagua-Inka |

13 |

14 |

|

|

Non-local LIP |

Colla |

9 |

9.7 |

|

Local LIP |

Collagua |

9 |

9.7 |

|

Collagua-2 |

7 |

7.5 |

|

|

Local MH |

Local MH |

3 |

3.2 |

|

Poss. Formative |

Brushed, no slip |

37 |

39.8 |

|

Total |

93 |

100 |

Table 6-56. Diagnostic sherds from Huañatira 2 [A03-855].

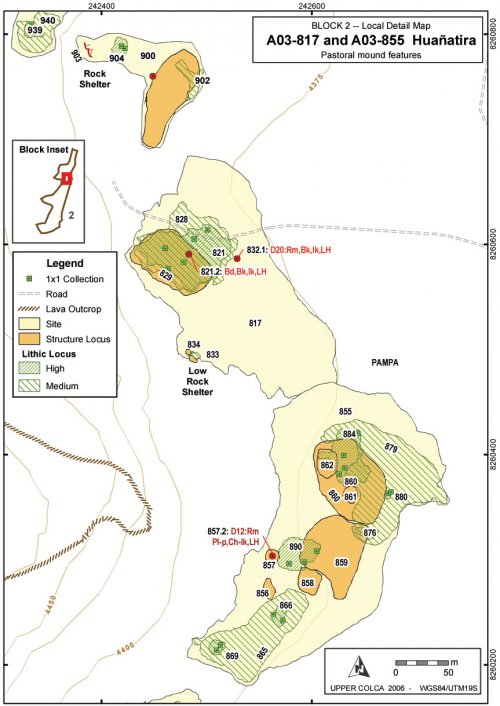

Figure6-75. Huañatira A03-817 and A03-855 multicomponent site showing corral structures.

Lithic reduction activities in this site complex appear to have been similar to those encountered at Pausa where obsidian reduction seems to have been occurring with frequency. The pattern results in a large percentage of small obsidian flakes and relatively small cores as compared with other material types.

Immediately to the north of the Huañatira sector described here, a rock shelter [A03-957] with an Archaic Period component was encountered that also contained the remnants of a cist tomb (shown on Figure 6-20).The cist consists of a recessed circle [A03-958] that is 3.17m in diameter north-south, and 3.22m in diameter east-west, and 54 to 60cm deep. Twenty slab stones were used to face the circle. The remnants of a wall is visible just inside the dripline of the shelter, and the circle is 2.16m to the north of this wall.

Figure 6-76. Cist tomb with mortared stonework, view from inside shelter (see also Figure 6-21). Shrubs are growing on remains of wall, visible in background. A 1m tape is visible inside the stone circle for scale.

Two crania were found with notable bilobate deformation. A number of long-bones were also evident (MNI = 2). The feature appears to have been a walled-in cave tomb that was perhaps looted long ago. The shelter is in a south-east orientation and so the area remains cool much of the time. It would make a tomb with cool temperatures that would slow down decomposition.

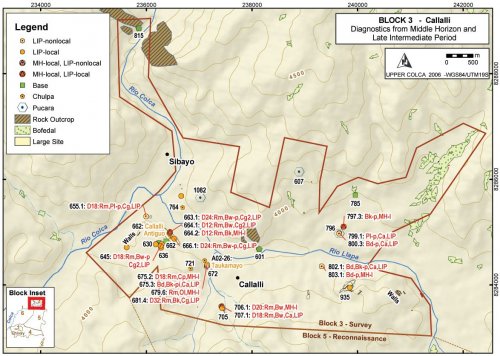

6.5.3. Block 3 - Callalli

In the Block 3 area, in the upper Colca valley, a significant increase in population and land use intensity is apparent from the distribution of settlement, mortuary features, and fortifications encountered in this region.

Block 6

Block 6 is located along the Challacone drainage just upstream from the town of Tuti, on the western edge of the study area. A map showing this survey block appeared in Figure 6-42. In addition to an interesting Archaic component, this area contained local MH, LIP, and local LH ceramics. Furthermore, the bases for five chulpaswere encountered along the ridgetop just east of Quebrada Challacone.

Discussion

The evidence from the Late Prehispanic occupation of Block 3 suggests that a significant population increase occurred during this time in the upper Colca valley. The evidence from the Tiwanaku period and the Middle Horizon appear to show small settlements with an economy focused primarily on pastoralism. Despite the wide circulation of Chivay obsidian during this period, there is no evidence in Block 3 of outside contact during the Middle Horizon except for the Wari influence in the local Middle Horizon ceramic technology, as described by Malpass and de la Vera Cruz (1986) and by Wernke (2003). During the Late Intermediate Period, dramatic changes are notable in a variety of forms of archaeological evidence in a pattern that is consistent with that observed by Wernke in the main Colca valley. Some limited agricultural cultivation appears to have been practiced given the association of LIP ceramics with cultivated areas. Pukara construction and some types of chulpaburial monuments are further evidence of LIP period occupation.

Late Horizon

In the Block 3 area the Late Horizon appears to involve the settlement of larger communities along the wide terrace margins of the Río Llapa. Sites associated with cultivated areas that had a slight Middle Horizon component and a stronger LIP component, appear to be the most extensively occupied under Inka dominance in the Late Horizon. The LH pattern of large settlements adjacent to agricultural lands is consistent with the pattern observed elsewhere in the highlands of southern Peru. In the Lake Titicaca Basin, Stanish notes that the settlement hierarchy for sites under 2.5 Ha remained mostly unchanged with the onset of the LH, but under Inka rule new large administrative sites were founded (Stanish 2003: 253-258). In the main Colca valley, Wernke (2003: 217-224,439-441) concludes that Inka administrative strategy involved ruling through local elites using the pre-existing ayllustructure of community organization. The effect on the settlement system was to promote a single administrative center, Yanque, to the top of the settlement hierarchy and other LIP sites became second-tier centers.

In the Callalli area, Late Horizon diagnostic ceramics were appear to have been concentrated along the south margin of the confluence area, known as Callalli Antiguo, and a small concentration of Late Horizon materials were found on the south-western edge of modern Callalli. The town of Sibayo, on the north side of the river confluence, was outside of the 2003 survey boundary, but it is possible that a Late Horizon settlement exists in that area as it complements Callalli Antiguo on the south. It is worth nothing that a principal prehispanic road along the Upper Colca valley lay on the south bank of the river where the route passes through to Canocota en route to Chivay. This road appears to have passed by the confluence area in the vicinity of Callalli Antiguo and as a major thoroughfare it is an appropriate place to position an administrative center.

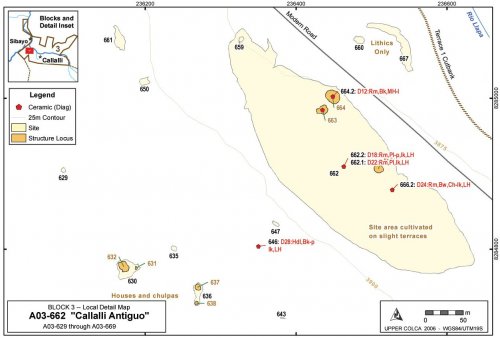

Figure 6-80. Block 3 Late Horizon diagnostic materials

To the west of Callalli the 2003 survey encountered a settlement that is known locally as "Callalli Antiguo" (F. Windischhofer 2003, pers. comm.). The site sprawls over the natural terraces just south of the confluence of the Colca with the Llapa, across from Sibayo. An extensive part of the site is located adjacent to the main road, while a cluster of collapsed structures, including houses and chulpas, are located just on the southern side of a ridge that divides the site in half. One might expect to find an Inka administrative site in this area. If this were an administrative site, however, it would also be fitting to encounter a number of well-constructed structures with Inka features, such as trapezoidal doors and cut-stone masonry as observed by Wernke (2003) at a number of sites in the main Colca Valley

Figure 6-81. Callalli Antiguo [A03-662] and surroundings.

Figure 6-82. A03-662 north sector of Callalli Antiguo agricultural sector, with two individuals walking together in the center of the photo providing scale and the Río Llapa and the town of Callalli in the background.

Vestiges of terraces are apparent in this larger, 4.2 hectare cultivated area of A03-662, and the sector appears to have been in agricultural production at one time where it is may have been involved in dry land production of high altitude seed-plants Chenopodium. Old natural terraces of the Río Llapa, slight terraces visible in the site overview photo below (Figure 6-82), were plowed and planted using field boundaries that follow terrace edges accentuated by the rocks that were thrown along the margins during field clearing. Some suggestion of eroded canal features were evident as well, implying that some form of irrigation was achieved, although such irrigation would likely have required diverting water from Quebrada Taukamayo to the east (adjacent to A02-26, see Figure 6-62)

Middle Horizon and Late Intermediate Period

As has been discussed above, the role of regional states in the Colca valley during the Middle Horizon is somewhat enigmatic. Wari influences are apparent in architecture and ceramic attributes, but direct evidence of Wari control has not been encountered. No evidence of Tiwanaku, a principal consumer of Chivay obsidian, has been encountered in the region. The local Middle Horizon ceramic type defined by Wernke (2003) was encountered in low densities in Block 3, although generally in spatial association with LIP sherds suggesting a continuity of economic and settlement patterns.

During the Late Intermediate Period there appears to have been a significant increase in population in the Block 3 region. The founding myth of the Collagua people, as recorded by a Spanish ethnohistoric source, has them conquering the Colca valley upon their descent from the Mount Collaguata near Velille in Espinar (Cusco) 120 km north of this region (Ulloa Mogollón 1965 [1586]; cited in Wernke 2003: 80). Data is not available from this surface survey to test the alleged population replacement, but some continuity in land use pattern is apparent from the occupation of areas with both local Middle Horizon ceramics and LIP ceramics.

One site that shows ceramics from throughout the sequence that includes the possible Formative Period (Chiquero), the Middle Horizon, LIP, and Late Horizon, is the site of Taukamayo [A02-26] discussed in more detail in Early Agropastoral section (seeFigure 6-60). This site has been partially destroyed by a creeping landslide that has resulted in shuffling of stratigraphy within the displaced slump deposit and the exposure of a variety of artifacts from the prehistoric sequence. In the creep debris there are concentrations of stone associated with LIP and LH ceramics that suggest that chulpas, perhaps similar to the one observed at a site immediately to the north [A03-673], were built along the terrace that has since collapsed in the creep.

Figure6-78. Block 3 Middle Horizon and Late Intermediate Period features.

Figure6-78. Block 3 Middle Horizon and Late Intermediate Period features.

Distinctive features from the LIP include a number of shared features from the Titicaca Basin mentioned previously. These consist of pukaras, chulpasand distinctive types of cave burials. Pukaras are fortified hilltops settlements usually occupied only for short-term, defensive purposes (Arkush 2005;Stanish 2003: 209-218;Wernke 2003: 251-265).

Agricultural production

While agriculture is very limited in the modern economy of the Callalli area, evidence of relatively extensive past agriculture is apparent along the Terrace 1 and 2 margins of the Río Llapa. In the vicinity of A03-785 and A03-797 on the east side of Block 3, extensive areas of previously furrowed agricultural lands are evident. Artifact associations with these agricultural lands primarily belong to the Late Intermediate Period and Late Horizon, but the remains of a colonial site near A03-785 is apparent as well.

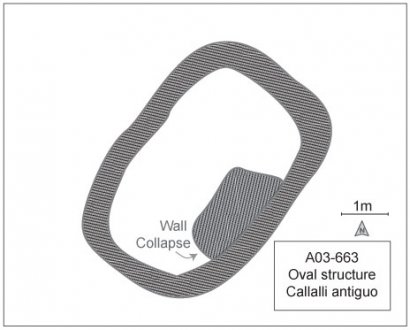

Structures

On the north side by the road an agricultural sector was encountered with a half-dozen collapsed rock structures including three structures of rounded rectangular form that may have been domestic. These three structures have walls that were constructed using a double coursed design with mortar, and the walls tilt slightly inward. Wernke (2003: 197-199) describes circular houses as being common for pastoral peoples in the higher altitude portions of the Colca valley beginning at the site Laiqa Laiqa near Tuti around 3900 masl. Rounded-rectangular structures are therefore unusual at this altitude in the valley. The double coursed walls of A03-663 measured approximately 90cm in thickness. Other possible explanations for these structures are that they served as storage silos (although the Late Horizon Qolqa storage silos are not found in the Colca valley), or these buildings could have been large burial towers. The ceramics collected in the immediate vicinity of these buildings span the Late Prehispanic with a single local Middle Horizon sherd, several LIP Collagua sherds, and Collagua-Inka LH sherds.

|

Figure 6-83. Base of walls of structure |

Figure 6-84. Collapsed wall of A03-663 structure. |

Ceramics

Surface collections of pottery from the area of Callalli Antiguo reveal that the site is a multicomponent occupation, but that the area appears to have been primarily a Late Horizon settlement. No brushed, unslipped pottery similar to the Chiquero Formative described by Wernke (2003) for the main Colca valley was found in this area.

|

Period |

Style |

Beaker |

Bowl |

Pitcher/Jar |

Plate |

Unknown |

Total |

|

LH |

Chucuito-Inka |

1 |

1 |

||||

|

LH |

Inka |

1 |

2 |

3 |

|||

|

LH |

Collagua-3 |

2 |

2 |

4 |

|||

|

LH |

Collagua-Inka |

1 |

1 |

||||

|

LIP-LH |

Collagua |

1 |

1 |

1 |

3 |

||

|

LIP |

Collagua-2 |

3 |

3 |

||||

|

MH |

Local MH |

1 |

1 |

Table 6-57. Diagnostic ceramics from Callalli Antiguo [A03-662] and vicinity.

The ceramics data suggest that this area, which does not have a pukara adjacent to it, was settled following the Inka conquest in the Late Horizon.

Lithics

A relatively large percentage of obsidian cores were observed at this site, particularly in the southern sector by the houses and chulpasshown on Figure 6-79. It is notable that one half of the fifteen Ob1 cores found in Block 3 were found here, and they are relatively large cores for Block 3.

|

Callalli Antiguo Cores |

Block 3 Surface Collection |

|||||||

|

Material |

No. |

m % Cortex |

mWt |

sWt |

No. |

m % Cortex |

mWt |

sWt |

|

Obsidian |

7 |

10 |

35.9 |

6.82 |

17 |

5.0 |

23.2 |

13.1 |

|

Volcanics |

1 |

20 |

117.8 |

- |

2 |

7.5 |

87.7 |

42.6 |

|

Chalcedony |

1 |

20 |

27.1 |

- |

4 |

16.7 |

47.5 |

18.1 |

|

Chert |

3 |

42.1 |

61.6 |

32.3 |

18 |

32.1 |

57.17 |

33.8 |

|

Total |

12 |

32.1 |

48.4 |

29.0 |

41 |

21.6 |

43.6 |

31.3 |

Figure 6-85. Cores at Callalli Antiguo [A03-662] and vicinity compared with all of Block 3.

It appears that obsidian cores were being transported here from the Maymeja area disproportionately to the rest of Block 3. The other site with a large number of Ob1 obsidian cores (n=6) is Taukamayo [A02-26] that was tested with the A02-26u1 unit and the u2 profile.

Mortuary features

Chulpaburial towers (Stanish 2003: 229-234;Wernke 2003: 225-233) are found throughout the Block 3 area on promontories and sometimes in caves or niches in cliff faces. Chulpaswere constructed during the LIP and LH in this region, while cist tombs are known to date from the preceding Middle Horizon. Few Block 3 chulpasare standing, and many of the stones appear to have been reused in nearby modern field walls. Cave burials were also encountered where the interments were "cocoon bundle" burials (de la Vega, et al. 2005;Wernke 2003: 233-234); this kind of interment was evident in the partially looted cave burial of A03-815 on the north end of the Block 3 survey area.

|

Figure 6-79. Recently looted cocoon-type interment from A03-815. |

Pukaras

A number of pukaras were encountered in the Block 3 area survey. Several of these [A03-607 and A03-796] include only small construction efforts on single walls, while a few pukaras had two or three defensive walls and structures on top, such as A03-1082. The most extensive evidence of pukara construction in Block 3 comes from A03-935, a large pukara on top of the lower sector of the Castillos de Callalli (the lower formation is also known as Cabeza de Leon) with natural escarpments over 50m high that were supplemented by four rows of walls on various areas of the hill. Three rows of walls were also encountered blocking access via the gullies close to Quelkata cave. This pukara represents a large, defensible zone.

Another relatively large pukara, Condorquiña [A02-6] was encountered in 2002 just over 5 km south along the west side of the Pulpera drainage (shown in Figure 6-69). Pukara Condorquiña has three major rows of walls and the remains of 10 oval structures on the summit the majority of them measuring about 1.8 x 2.3 m across.