2.2. Anthropological approaches to economy and exchange

It is a critical limitation of archaeology, particularly when not given powerful assistance from historical sources, that it remains tied to the spatial distribution of imperishable objects or non-artifactual materials whose temporal sequence is seldom more than very roughly defined. Questions normally asked by archaeologists about trade and diffusion have been those which they can (or think they might be able to) answer directly and incontrovertibly from their data. But we must ask whether such questions are the important ones for an understanding of human society (Adams 1974: 139-140).

2.2.1. Economies

The study of ancient economies has long been a central theme in archaeological research. Lying at the intersection of human behavior and material goods, economy can often provide a theoretical basis for connecting features and artifacts with larger scale traits in prehistoric societies. Economic approaches to prehistory have the promise of bridging the premodern individuals and institutions of anthropological study with their material remains in a quantifiable way in order to examine processes such as change in subsistence, intensification, and exchange.

A fundamental question in economic anthropology concerns the cross-cultural applicability of economic models developed primarily for explaining behavior in Western, market-oriented societies. In the past 50 years economic anthropology has witnessed protracted debates between advocates of formal and substantive approaches to economy (Plattner 1989: 10-15). The perspective put forward by formalists is that ancient and non-western societies differ from those of modern capitalist societies in degree but not in kind (Wilk 1996). In contrast, substantivists recognize fundamental differences between ancient or non-capitalist societies and modern economies. These debates have been reconciled to a certain extent with the recognition that the two approaches largely complement each other. The distinct assumptions associated with formal and substantive economics, however, are critical to framing research questions about ancient economy, commodities, and exchange.

Formal approaches

Formal approaches explore the outcome of rational decision-making with regard to choices faced by prehistoric populations. By conceiving of economic behavior in terms of universal rationality, these approaches are analytically useful because they allow for the isolation of variables and for cross-cultural comparisons. Formal economic analyses are built on studies of modern markets by human geographers and involve reducing labor, land, and capital to the price as the unit of cost. Anthropologists using formal approaches may apply energy or time as value units to studies of food procurement, raw material provisioning, and settlement choice as in studies by behavioral ecologists (Winterhalder and Smith 2000) and archaeologists (Earle and Christenson 1980;Jochim 1976;Kennett and Winterhalder 2006).

Formal approaches to prehistoric exchange have been used by archaeologists to study the evolution in exchange systems both organizationally and from the perspective of individual behavior (Earle 1982: 2). On the larger scale, regression analysis (Hodder 1978;Renfrew 1977;Renfrew, et al. 1968;Sidrys 1977) and gravity models (Hodder 1974) use assumptions of cost minimization to differentiate between possible exchange systems in prehistory. "The sociopolitical institutions establish constraints in terms of the distribution and value of items. Then, individuals, acting within these institutional constraints, procure and distribute materials in a cost-conscious manner" (Earle 1982: 2). Neoclassical assumptions on the scale of individual behavior have also been used to examine the evolution of market based exchange (Alden 1982) and subsistence goods exchange by territorial groups exploiting high-yielding yet unpredictable resources (Bettinger 1982). A synthesis by Winterhalder (1997) investigates the way in which complex exchange behaviors that have been documented ethnographically can result from models of circumstance such as tolerated theft, trade and risk reduction, and models of mechanism such as kin selection and dual inheritance.

Critiques of formal approaches have been various, with strong methodological criticism coming from influential ex-formalists like Ian Hodder. On the subject of exchange, Hodder (1982: 202) observes that the explanatory power of formal approaches to prehistoric exchange are significantly weakened by the problem of equifinality in the empirical evidence, an issue discussed below. Hodder further argues that middle range links between social contexts, political strategies, and the empirical evidence provided by distributions of archaeological data are insufficiently accounted for with formal approaches such as regression analysis.

Substantive approaches

Substantivism arose in anthropology largely in response to what was perceived as the inapplicability of formal approaches and the assumptions of neoclassical economics to ethnographic case studies (Wilk 1996: 1-26). Substantive approaches emphasize that economy and exchange are fundamentally linked to other aspects of human behavior. To substantivists, economic institutions are effectively cultural traits, therefore techniques designed around "modern" or "western" conceptions of rational individualism are inadequate for application in non-western cultural contexts (Bohannan and Dalton 1962;Dalton 1969). The position was first articulated by Karl Polanyi (1957) that the economy is "embedded" in sociopolitical institutions. This view of economy and non-western exchange has its roots in studies by Malinowski (1922) and Mauss (1925), although the focus in that earlier period of economic anthropology was on social relationships, whereas social change dominated the discourse in economic anthropology during the 1960s (Dalton 1969).

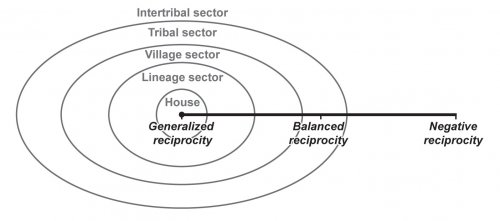

Mid-twentieth century substantivism was based on a functionalist view of society as static and aspiring to the maintenance of equilibrium within the social environment (Schneider 1974). Interaction took place through reciprocity, redistribution, and exchange. Sahlins' (1965) further elaborated on reciprocity based exchange by placing generalized, balanced, and negative reciprocities along a continuum that served to describe the dynamics of interaction within specific social contexts. Another distinction lay between the transfer of inalienable gifts between reciprocally dependent individuals "that establishes a qualitative relationship between the transactors" (Gregory 1982: 101) and alienable commodities as transfer between reciprocally independent people "that establishes a quantitative relationship between the objects exchanged" (Gregory 1982: 100).

A number of critiques have emerged of the substantivist approach. One critique of substantivist approaches to exchange, one that is true of functionalism more generally, is an early version of agency theory. In the substantivist view, society is constructed of consistent rules within agents must act and includes a moral obligation of exchange (Dalton 1969: 77). In this organic perspective, however, "[t]here is little room for individual construction of social strategies and manipulation of rules, and there is little intimation of conflicts and contradictions between interests" (Hodder 1982: 200).

A second critique focuses on the distinction drawn by substantivists between complex and small-scale societies. Among complex societies, formal approaches are supposed to be more relevant, but in the context of small-scale societies substantive approaches are appropriate, and this dichotomy creates a dilemma of where exactly to draw the line. Monica L. Smith (1999: 111) argues that the ethnographic cases to which many substantivist models refer (i.e., small-scale societies) are lower in population density and involve fewer layers of interaction than would have been found in premodern states and empires and therefore formal approaches might have more relevance in premodern complex societies than is presented by substantivists.

A third critique holds that the direct correlation between forms of exchange and level of socio-political complexity lacks empirical support (Hodder 1982: 201). Anthropological studies suggest that unpredictability in food supply correlates with more extensive reciprocal exchange systems. Reciprocity is encountered more frequently among hunters, fishers and farmers than among gatherers and pastoralists who exploit relatively predictable resources (Pryor 1977: 4).

In the current day, Polyani's framework centering on the distinction between reciprocity, redistribution and market forces continues to be widely used in anthropology and archaeology, despite the development of alternative models that are particularly relevant to studies of commercialized pre-modern states. In particular, Michael E. Smith (2004) argues that more refined differentiation of transaction mechanisms can be used to distinguish the degree of internal and external commercialization in state-level societies, such as those presented by Carol A. Smith (1976). However, the subtleties of ancient commercial enterprise are less relevant in places like ancient Egypt and the Andes where historical and archaeological evidence attest to strong state control of uncommericalized economies without market-based economics, money, and independent merchants. In other words, Polyani's coarser distinctions of reciprocity, redistribution combined with non-market trade are sufficient in regions such as the ancient Andes where most scholars believe commerce played an minor role in prehistoric development (LaLone 1982;Stanish 2003). In Mesoamerica, however, where evidence for prehispanic markets and traders is widespread, anthropologists have found that Polyani's distinctions are vague and that models with further refinement in modes of commercialization are applicable (Braswell 2002;Smith 1976;Smith 2004).

Complementary applications of formal and substantive approaches

Formal and substantive approaches can be applied in a complementary manner. For example, in Stone Age Economics, Sahlins (1972) attempts to explain the existence of supply and demand curves among aboriginal exchange networks where social parameters determine the development of exchange. Winterhalder (1997) discusses some of the concepts presented by Sahlins (1972) using a behavioral ecology approach to gifts and exchange among non-market foragers. Winterhalder finds that issues such as social distance can be addressed more explicitly in a formal framework, albeit more narrowly, because economizing, neoclassical assumptions are a starting point for this type of analysis. As Hodder (1982: 200) points out, formal and substantive approaches are targeting different behaviors; formal economics relies on outputs and performance, while substantive analyses relate to social contexts of exchange.

While these differences make the two approaches irreconcilable on some levels, some studies attempt to integrate both avenues of research. Drawing on the advantages of both formalism and substantivism may be worthwhile, but a tendency to apply formal analyses to state-level societies, due to greater commercialism and specialization, and to apply substantive analyses to small-scale societies, should be resisted (Granovetter 1985;Gregory 1982;Smith 1999). The assumption that in premarket social contexts economic behavior is heavily embedded in social relations, but then is increasingly atomized and conforming to neoclassic analyses in modern, market-oriented societies is inconsistent. Granovetter (1985: 482) writes

I assert that the level of embeddedness of economic behavior is lower in nonmarket societies than is claimed by substantivists and development theorists, and it has changed less with 'modernization' than they believe; but I argue also that this level has always been and continues to be more substantial than is allowed for by formalists and economists (Granovetter 1985: 482).

Similarly, Danby (2002) observes that there are serious logical flaws in the false dichotomy, widely applied by archaeologists, where neoclassic, cost-minimizing logic is applied to premodern, complex societies but increasingly assuming an embedded "gift" economy among smaller-scale economies.

This dissertation research project follows on the substantivist tradition in the Andes, but formal approaches have been influential in exchange studies worldwide. The weaker elements of the substantivist approach will be avoided by not assuming a direct correspondence between socio-political complexity and volume or type of exchange.

2.2.2. Transfer of goods and exchange value

In the 1970s much of the debate had shifted from formalism and substantivism, to Marxism and structuralism. Marxists approach economic anthropology comparatively by focusing on production, arguing that society's basic forms of exploitation and inequality are continually being recreated in modes and relations of production (Godelier 1979). Structuralists hold that one had to understand the total system of meaning in order to interpret the relative value of items in a society, but they reject the functionalist assumption that economic institutions serve to integrate society (Graeber 2001: 18).

In the 1980s, the emphasis shifted to consumption. In an influential paper titled "Commodities and the Politics of Value," Arjun Appadurai (1986) states that anthropologists can more effectively examine cross-cultural patterns in economy and exchange by focusing on exchange from the consumption perspective. Appadurai follows Georg Simmel (2004 [1907]) in arguing that the source of an object's value is based in its exchangeability and the desire of the buyer, not the labor that went into production. As with formal approaches, this emphasis on exchange permits broad cross-cultural comparisons because exchange activities are universal characteristics of human behavior. Appadurai's approach shares some of the limitations of formal approaches. Appadurai focuses on the commodified value and the value that goods accrue primarily through transfer, which put constraints on the analytical potential for looking at the social and symbolic significance of human relationships organized around exchange. Rather, Appadurai investigates an object's "life history" as it has passed through multiple hands. The emphasis is shifted from two individuals exchanging goods to the relationship of equivalencies between the two objects being exchanged (Appadurai 1986: 12-17).

A notable challenge to Appadurai's contention that "circulation creates value" is Weiner's (1976: 180-183) observation that among the societies discussed by Mauss (1925) the value of the objects in question is associated with their original owners and their specific histories, and value is not the product of transfer. Thus, the value is not predominantly a result of demand, as asserted by Appadurai, and it is often the case that value reflects the inalienable properties of specific heirlooms some of which, like the royal crown jewels, do not circulate at all. Igor Kopytoff (1986: 74) describes a variety of items that have "singularity" due to restricted commercialization. Examples of this include ritual items or medicines in western society that are destined specifically for the intended patient that have prohibitions against resale. In his critique, David Graeber (2001: 34) suggests that for any society it might be possible to map "a continuum of types of objects ranked by their capacity to accumulate history: from crown jewels at the top, to, at the bottom, such things as a gallon of motor oil, or two eggs over easy". Unlike Appadurai, Graeber's approach places goods in a continuum that does not depend on transfer to establish the relative value of an item. The distinction between alienable and inalienable goods is linked to relative abundance and exclusivity of the products in question and to historic characteristics, like the degree of influence of a price-regulating market (Miller 1995).

Exchange and social distance

The dominant ethnographic approach in twentieth-century substantivist anthropology contrasts non-western gifting and exchange with capitalist, market-oriented trade in alienable commodities. Malinowski (1922) describes forms of exchange ranging from pure gifts to trade with increasing self-interest and "equivalence" as one moves towards the trade relationship. Mauss (1990 [1925]) attacks the notion of the pure gift and instead focuses on the temporal aspects of gift-giving, with the establishment of what are effectively ancient forms of credit. Further, Mauss focuses on the sociality of gift exchange with the idea that gifting can take hostile forms by inflicting obligations that the recipient may fear. Sahlins (1972: 191) subsumes the sociality of exchange relationships into a single trajectory with the concept of social distance. The "social distance" between exchange partners is a way of conceiving of the degree of familiarity and information transfer between producer and consumer of goods.

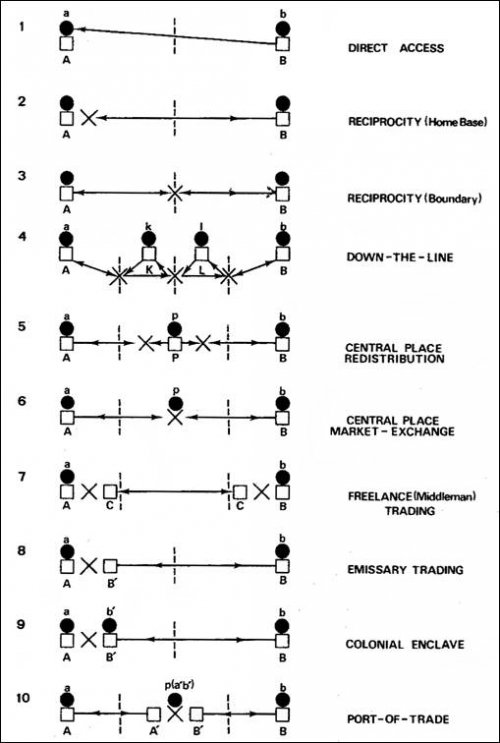

Figure 2-1. Varieties of reciprocal exchange (after Sahlins 1972: 199).

In Sahlins' classic taxonomy of reciprocity he identifies generalized, balanced, and negative reciprocity as a continuum from gift through exchange to haggling and theft, with explicitly different moral standards applying to transfers occurring in each sector. These modes of reciprocity were mapped directly on to increasing social distance originating in the household, although Sahlins was unspecific about the institutional forms of exchange, allowing for wide cross-cultural variation.

Besides the functionalist underpinnings of Sahlins' approach, one critique of his social distance model rests on his distinction between the role of the state and social relationships based on economic ties.

Because Sahlins is constructing a general theory, he is not obligated to deal with the refractory ethnographic data of one particular group. Hence, Malinowski's multiple heterogeneous categories of gifting never arise. In its place, Sahlins has a single Big Idea developed in the famous chapter on Hobbes and Mauss. The idea is that economics is politics for primitives. The understructure of human society, the default, is the chronic insecurity of Hobbes' "war of all against all." Primitives lack the state that is Hobbes' preferred remedy (Danby 2002: 24).

The result for Sahlins rests on a weak dichotomy between primitive|modern economic contexts that includes (1) primitive contexts where relations are mediated by social and economic relationships, and (2) modern contexts given over to the logic of neoclassic economics because commercialization and the circulation of alienable commodities are qualitatively different. Danby presents instead a "post-colonial critique [that] sees gift|exchange as yet another mapping of primitive|modern, an ultimately tautologous them|us split in which 'they' are various negations of what 'we' think 'we' are" (Danby 2002: 32). Anthropologists have sometimes followed this dichotomy where long-term investment and the establishment of social relationships in transactions is given over to the gift side, while exchange in alienable commodities is expected in complex, state level economies where exchange transactions are analyzed following the neoclassical approach and spot transactions are conducted in open markets.

In contrast, Danby argues that, if anything, one should expect greater temporal complexity and mechanisms for extending forward credit with greater social complexity.

Rather than building theory by pushing off against neoclassical exchange, let us put neoclassical exchange aside... the asocial spot transactions on the right-hand ends of [Sahlins' (Figure 2-1)] gift-exchange continua are also marginal to wealthy capitalist economies. Forward, debt creating transactions, embedded in social relations that often entail power, are central. Moreover, they are likely to be socially embedded in a variety of ways that should lead us to rethink the dichotomies between non-gift and gift (Danby 2002: 28).

Instead of framing the anthropological discussion of exchange in opposition to neoclassical approaches, Danby argues that the discussion should be reframed around institutions that underlie transactions in society and provide the long-term temporal milieu within which transactions occur. Temporality is particularly important when exchange is framed by production calendars based in agricultural cycles and by social calendars centered on gatherings and ceremonial occasions. By this standard, goods lying on the inalienable end of the continuum are fundamental to examining all economies in an anthropological light.

Common goods and luxury goods

The inalienability or uniqueness of an object sometimes parallels the categories of common and luxury items, with common items being mutable and replaceable. Yet, the classification as 'common' or 'luxury' for a given object is not discrete. It has been widely observed that the distinction between common and luxury items is contingent in space and time.

The line between luxury and everyday commodities is not only a historically shifting one, but even at any given point in time what looks like a homogeneous, bulk item of extremely limited semantic range can become very different in the course of distribution and consumption...Demand is thus neither a mechanical response to the structure and level of production nor a bottomless natural appetite. It is a complex social mechanism that mediates between short- and long-term patterns of commodity circulation (Appadurai 1986: 40-41).

Appadurai presents sugar as an example of a product with widely varying significance, and he observes that it is not merely the possession of exotic goods, but also the social significance of the knowledge surrounding the production or consumption of these goods, that carries significance. Goods that are irregularly distributed in space, portable, and that have wide consumption appeal such as sugar, salt and obsidian, were transported great distances in prehistory. For example, in the Mantaro Valley of the central Andes, Bruce Owen (2001: 280) notes that a number of metal items such as copper needles went from being wealth goods found primarily in elite contexts prior to the Inka conquest, to being utilitarian items and found with equal frequency in commoner contexts under Inka rule.

The movement of commodities has the significant effect of reinforcing relationships between social groups in the sense that the Kula ring promotes regular contact (Malinowski 1984 [1922]). However, in circumstances where the elite strive to control consumption of commodities, exchange can threaten the position of the elite. In Appadurai's perspective, both rulers and traders are the critical agents in articulating supply and demand of commodities.

The politics of demand frequently lies at the root of the tension between merchants and political elites; whereas merchants tend to be the social representatives of unfettered equivalence, new commodities, and strange tastes, political elites tend to be the custodians of restricted exchange, fixed commodity systems, and established tastes and sumptuary customs. This antagonism between "foreign" goods and local sumptuary (and therefore political) structures is probably the fundamental reason for the often remarked tendency of primitive societies to restrict trade to a limited set of commodities and to dealings with strangers rather than with kinsmen or friends. The notion that trade violates the spirit of the gift may in complex societies be only a vaguely related by-product of this more fundamental antagonism (Appadurai 1986: 33).

The suggestion that exchange promotes contact that threatens elite control results from either a relatively independent group of traders, or competing elites that utilize external contacts to advance their positions. Appadurai's point, however, is that in the realm of political finance one might expect established elites to strive to exert greater control over the values of production and exchange rather than relegate this important issue to those who traffic in long-distance goods, such as caravan drivers.

Following Polanyi, one might expect to find that in complex, premodern societies without market-based exchange there was dominance of administered trade. However, a number of scholars have observed that Polanyi (1957) appears to have ruled out precapitalist commercialism in ancient states a priori, as he claimed that there were no true markets or prices that reflected supply and demand in the ancient world, but rather equivalences in value that were set by rulers in an administered context. These "dogmatic misconceptions" (Trigger 2003: 59) appear to have caused Polanyi to distort the historical evidence as his views of administered markets in premodern states have been widely refuted (Smith 2004: 75-76;Snell 1997). Historian Philip Curtin (1984: 58) observes that even within contexts of administered control traders may have had more freedom than previously thought.

In some regional contexts, such as the prehispanic Andes, Polanyi's interaction types continue to be viable because there is little evidence of commercialization and open markets. The prevailing interpretation of prehispanic economy, for the Inka period in the central Andes at least, is "supply on command" (LaLone 1982) with elite economic domination primarily through labor mobilization. This issue will be explored in more detail in the Chapter 3, but Andeanists have largely found that Polanyi's non-commercial typology of premodern exchange suffices for analyses of prehispanic Andean economies.

Exchange promotes interaction between communities, yet Appadurai also explains that "such a tendency is always balanced by a countertendency, in all societies, to restrict, control, and channel exchange" (1986: 38). Under the rubric of "politics of value" Appadurai describes a pattern of institutional or elite control of commerce monopolizing or redirecting the flow of commodities. On this issue Graeber characterizes Appadurai's 1986 framework as "neoliberal" and describes it as follows

Appadurai leaves one with an image of commerce (self-interested, acquisitive calculation) as a universal human urge, almost a libidinal, democratic force, always trying to subvert the powers of the state, aristocratic hierarchies, or cultural elites whose role always seems to be to try to inhibit, channel, or control it. It all rather makes one wish one still had Karl Polanyi (1944) around to remind us how much state power has created the very terms of what is now considered normal commercial life (Graeber 2001: 33).

Appadurai cites examples of historic royal monopolies and sumptuary laws restricting trade items in Rhodesia and renaissance Europe support his argument (Appadurai 1986: 38). However, without the state-organized overhead of basic institutions guaranteeing peace, investment, and the protection of property, the movement of goods would involve much more danger of theft by brigands or goods could be simply confiscated by rival authorities.

Appadurai's focus on consumption is a significant contribution in that it releases anthropologists to address activities specifically related to consumption behavior, even though the neglect of production presents an incomplete picture of economy. Consumption loci are often the contexts where the strongest evidence or patterning of interaction is found. Thus, consumption is particularly useful to archaeologists who may only have evidence of changing consumption patterns, or who must infer links between production and consumption indirectly.

Exchange in subsistence, cultural, and prestige technologies

The distinction between the circulation of common and luxury goods observed by anthropologists can be considered in terms of the larger economy and the organization of technology by linking these concepts to those of practical and prestige technologies. As described broadly by Hayden (1998), practical technologies are those that are primarily organized around principles of sufficiency and effectiveness, while the logic of prestige technologies is fundamentally different because it is oriented towards social strategies where greater labor investment in products serves to communicate the wealth, success, and power of the parties involved. A third category, termed cultural goods, will also be used to examine the relationship between material culture and exchange. The concepts of practical, cultural, and prestige goods will be used to link long term changes in the organization of technology and production with consumption patterns and socio-political evolution.

This framework is relevant to this discussion of anthropological approaches to exchange because it places the contrasting behavior that Appadurai terms "common" and "luxury" goods into an empirical and evolutionary framework capable of addressing change over long time periods. Thus while the earlier discussion of "luxury goods" that transcend social and political boundaries referred to particular contexts of circulation, these are specific manifestations of goods Hayden would include in the broad category of prestige technology, as these objects are labor intensive to produce or acquire.

The concepts of practical and prestige technologies parallel in some ways the economic distinction made by Earle (1987;1994) between subsistence and political economies. The household level subsistence economy is based on satisficing logic, while the political economy involves the mobilization of surpluses and competition between political actors, and is subject to the maximizing strategies of elites. The organization of technology is sometimes approached in terms of three groups as Binford (1962) has done with "technomic", "sociotechnic", and "ideotechnic" categories. For Binford, technomic objects correspond to "practical technology", and the sociotechnic and ideotechnic groups would largely, but not exclusively, overlap with "prestige technologies". Hayden (1998: 15) observes that labor inputs are low but sociotechnic significance is high in Australian Aboriginal string headbands that signal adult status, and labor is low but ideotechnic significance is high in a pair of crossed sticks tied together to represent a crucifix. Hayden points out that despite these exceptions, items of ritual and social significance are often made with relatively costly materials (such as gold crucifixes) but he admits that many items fall between his categories such as decorated antler digging-stick handles, and "the analysis of such objects becomes especially complex where the prestige materials such as metals or jade are actually more effective, but far more costly, than more commonly used materials" (Hayden 1998: 44-45). Obsidian presents a similar dilemma where, on the one hand it is rare in many regions, and it is unusual-looking, and yet it is also more effective for many kinds of cutting functions and so the inducement to use the material is not straight-forward. As an object can move between categories it should be said that ultimately the significance of an item is not an inherent property of the object, but rather it is created by contexts of use or consumption and should best be considered in terms of labor, exchangeability or life-history (Appadurai 1986;Graeber 2001).

|

Category |

Distribution |

Examples |

|

Subsistence Goods |

Practical technology. As a response to stresses item must be effective. Widely available, minimizing costs due to satisficing logic, distributed shorter distances. |

Simple tools: axes, saws. Simple baskets and pottery. Bulky, low value foods (i.e., cereals, tubers). Common metals (later Old World prehistory). |

|

Cultural Goods |

Widely available goods, but with information content and social and ideological significance. Aesthetic but non-labor intensive and non-exclusive designs. |

Some projectile technology. Textiles, shell, herbs and medicines such as coca leaf. Items for commonplace rituals. |

|

Prestige Goods |

High labor inputs, investment logic due to political potential of consuming labor, sometimes wide distribution in circumscribed contexts. Competition may mean that these are consumed or destroyed. |

Rare metals; serving vessels: ceramics, baskets; jewelry; tailored clothing. Musical instruments, high value foods, rare or costly herbs and medicines. |

Table 2-1. Three categories of exchange goods, the boundaries on these categories are contingent on contexts of production, circulation, and consumption. Many items like meat, maize, and obsidian tools can belong in any one of these groups depending on form and availability.

According to Hayden (1998: 44) any material that is transported more than two days should probably be considered a prestige technology due to labor investment, however he mentions that perhaps a useful intermediate category of "cultural goods" could be defined consisting of non-prestige ritual or social artifacts. In his analysis of long distance caravans in the Andes, Nielsen (2000: 66-67) borrows concepts from Hayden's practical and prestige technologies with some modification for a discussion of exchange goods. Nielsen defines "subsistence goods" and "prestige goods", but he also defines a third category as "cultural goods" to include maize used for subsistence but also for ritual, as well as coca and textiles. These goods are often non-exclusive, but their form and consumption carries significance and the circulation of such items does not conform to the satisficing logic of practical technologies and subsistence goods.

Ordinary goods and archaeological theory

The fact that many artifacts cannot easily be classified into one of the above groups in a particular time or cultural context shows the difficulties inherent in developing a generalized framework for addressing production and exchange through prehistory. Obsidian is a prime example of a material that has practical value, but it is visually distinct and it is also a material with cultural significance and prestige associations in some contexts. Thus, while the focus in exchange studies has been on prestige goods linked to status competition, because these activities have evolutionary consequences, subsistence goods may also contain social or cultural information. The association of items luxury or commonplace categories is a function of geography, technology, and socially defined valuation.

Information content and everyday goods

Monica L. Smith (1999) develops an argument based on a dichotomy between "luxury goods" and "ordinary goods", where some of the ordinary items used in household activities and moved through kin-based exchange networks form an important, material component of group identity. This essay could also be used to support an argument for an intermediate category of cultural goods. Smith notes that the circulation and consumption of such ordinary but visually distinct household goods serve to maintain cultural links and symbolize status markers that probably precede, and indeed form the structure for, later social ranking. She observes that archaeological discussions of exchange often falsely imply that exchange links were established by an exclusive elite population and these links eventually become established and expand to ordinary goods.

Brumfiel and Earle (1987: 6) find the distinction between luxury and utilitarian goods setting the stage for the organization of economic activity in early complex societies, citing "... the lack of importance of subsistence goods specialization for political development." The sequence in which different types of goods are incorporated into exchange patterns is explained as an evolutionary sequence paralleling developments in sociopolitical complexity, so that "as trading routes and trading relationships became more firmly established, everyday goods were added to the merchants' repertoire...and came to supply not only valuable items for elites but also food staples and utilitarian wares for people in the society generally" (Berdan 1989: 113; cited in Smith 1999: 113).

Some scholars have historically placed a priority on the influence of status or luxury goods by elites in some centralized political sphere in stimulating and maintaining long distance trade links (Brumfiel and Earle 1987;Smith 1976), arguing that the political objectives of elites and aspiring elites were the impetus for long-distance links. Yet as M. L. Smith (1999) applies the socio-semiotics of Gottdiener (1995), the consumption of particular materials can have social significance and can convey information content at a variety of levels. Thus the capacity for kin-based reciprocal exchange networks to distribute household items over distance, or household level caravans to emphasize relatively mundane products, should not be underestimated.

The intent of many archaeologists focusing on the role of status goods exchange seems to be not necessarily to deny the capacity and symbolism of household-level exchange as much as it is to emphasize the political and economic significance of exchange in status goods controlled by elites. Goods that circulate widely within a particular community may serve to express community participation or corporate affiliation (Blanton, et al. 1996). Hayden's distinction of practical and prestige technologies focuses instead on effectiveness, for the first group, and high labor inputs for the second. Thus, to reconcile this with M. L. Smith's argument, the third group that includes "cultural goods" conveys important social and ideological information beyond the satisficing "effectiveness" stipulation, but simultaneously is widely available and cross-cuts social hierarchy.

Availability and consumption patterns

One reason that subsistence goods, cultural goods, and prestige goods are non-exclusive categories is that consumption patterns associated with these goods have changed as availability changed through time. The availability of a given material changes through time, be it obsidian in the prehispanic Andes or glass drinking vessels in ancient Rome, and availability conditions the importance of its consumption (Appadurai 1986: 38-39;Smith 1999: 113-114). In cases of intensified craft production, availability may be determined by labor specialization, production units, intensity, locus of control, and context of production (Costin 2000). With commodities based on raw materials, the primary determinant of availability in most cases is geographical distance from the source, but economic patterns, socio-political barriers, technology of procurement and transport, and rate of consumption all affect availability.

Along with naturally occurring raw materials that are irregularly distributed across the natural landscape, such as obsidian where sources are rare, one may expect behaviors associated with scarcity to apply to geologically occurring minerals only with diminished availability as one moves away from the source of these goods. Thus the availability of goods such as obsidian over the larger consumption zone for these materials will vary from abundant to scarce depending on geographical relationships and socio-economic links between the source and the consumption zone. The archaeological study of commodity distribution, and in particular the relationship to economy and to socio-political evolution, spawned years of research into regional exchange beginning with the work of Colin Renfrew (1969) and that of his colleagues.

The circulation of flaked stone

Focusing here on the differences in artifact use in regions where raw materials are abundant, versus those places where they are rare, permits several generalizations with regards to raw material consumption. As a material class, flaked stone is durable and often the material is sourcable to geological origin point and due to these features, lithics analysis share some attributes with consumption studies of other artifact classes. One characteristic that differentiates lithics is that they are among the more resilient archaeological materials, and are sometimes used as a proxy for mobility or exchange. However, the lithics material class is comparable with other artifacts of consumption like ceramics, food goods and textiles, in that lithics are used to produce goods that range from mundane or subsistence-level to elaborate forms that imply the goods were inscribed with social or ritual importance.

Lithics have important differences from other artifact classes, however. Principally, the production of stone tools is a reductive technology and flaked stone tools inevitably become smaller with use. This directionality of lithic reduction, which allows for technical analysis and refitting studies, signifies that, unlike metal projectiles, textiles, and other widely exchanged materials, the down-the-line transfer and use of lithics has distinctly circumscribed use-life based on reduction. The second major implication of the reductive nature of stone is in regards to the social distance between the producer and consumer. As stone artifacts become inexorably smaller with production and use, larger starting nodules can take more potential forms and have a generalized utility that is progressively lost as reduction proceeds. In terms of the exchange value of a projectile point as a "cultural good", the roughing out of a lanceolate point, for example, may have determined the cultural value of the preform such that it would have had less potential, and therefore less value, in contexts where triangular points are used. With scarce lithic raw materials the size of the item probably related directly with its reduction potential; therefore larger nodules would probably have had value in a wider range of consumption contexts.

Lithic procurement, distribution, and consumption are in some ways comparable with other classes of portable artifacts, and in some ways quite distinct. Archaeologists have used the spatial relationships between lithic raw material and behavior to study the ways in which the availability of a particular material type affects prehistoric behavior with respect to production, curation and mobility (Bamforth 1986;Luedtke 1984;Shott 1996). Procurement, distance from source, and the embedding of lithic provisioning in subsistence rounds have specific consequences with respect to raw material use in the vicinity of a geological source area (Binford 1979;Gould and Saggers 1985), an issue to be discussed in more detail below. Regardless of mode of transfer and other distributional issues, the use of lithic raw materials, as with other artifact classes, is contingent on variability in a number of dimensions. These dimensions include whether the material is abundant or rare, lightly or intensely procured, laden with cultural or prestigious associations, as well as circulation and demand, although many of these variables can be difficult to isolate archaeologically.

2.2.3. Transfer of goods and socio-political complexity

Prehistoric exchange has long been central in anthropological and economic models of socio-political change. Exchange has been discussed by social theorists, anthropologists and archaeologists the debating the ultimate causes of socio-political inequality that emerged independently during the Holocene in different regions of the world. In the course of the last 12,000 years, archaeological evidence documents a change from a worldwide of hunting and gathering groups with relatively egalitarian, village-level social organization to, in a few places world-wide, in-situ development of state-level society with large settlements, greater concentration of wealth, and hierarchical economic and political organizations. While anthropological models accounting for political and economic change have been refined over the past century, evidence of exchange has consistently served as a material indicator of regional interaction and differential access to exotic goods within a community.

Exchange as a prime mover?

Regional exchange is of particular utility to anthropological archaeology because it is a material phenomenon that occurs at the intersection of social relationships, resource procurement, and individual or community differentiation. However, exchange has been attributed with great causal significance in the past and, while it provides evidence of particular utility to anthropologists and archaeologists, it is important to not ascribe excessive significance to exchange in human affairs. For example, to V. Gordon Childe (1936) long distance trade was a prime mover that had direct social evolutionary consequences. Engaging in trade had derived benefits that can affect the balance of power between competing polities and stimulate larger forms of organization.

In the 1970s, Rathje (1971;1972) proposed that it was the lowland Maya need for "essentials" like obsidian, salt, and grinding stones that propelled them to seek external sources for these scarce goods, initiating long-distance relationships. Those who control access to scarce materials accrued benefits from their position in the trade network, he argued, and hierarchies emerged from the differential access to these required, or desired, trade goods. Virtually all of Rathje's postulates have since been disproved, but some variant of the theme first articulated in Rathje's exchange model underlies many contemporary investigations of ancient trade (Clark 2003: 33-34).

In the multilinear evolutionary framework of Johnson and Earle (1987), trade is part of an array of processes that are relevant to socio-political development, but trade does not become a dominant process until the formation of the Nation-State.

|

Economic Processes in Political Evolution |

|||

|

Local Group |

Regional Chiefdom |

Early State |

Nation-state |

|

WARFARE |

warfare |

warfare |

warfare |

|

risk management |

RISK MANAGEMENT |

(risk management) |

(risk management) |

|

technology |

technology |

TECHNOLOGY |

(technology) |

|

trade |

trade |

trade |

TRADE |

Table 2-2. Economic processes in political evolution (Johnson and Earle 1987: 304) where capitalized words indicates a dominance of that process, parenthesis indicate important secondary processes.

The approach taken here is that all human groups engage in exchange in some form and it therefore serves as a consistent index of regional relationships through time. Furthermore some trade items, such as obsidian, appear to have been part of a suite of features that, at particular times and socio-political contexts, serve to differentiate individuals or groups from the rest of their community for purposes relating to political strategy. While exchange is not a prime mover for socio-political change, transfer between peoples and groups in different forms provides a vehicle for social differentiation and a materialization of geographical relationships that are closely linked to socio-political organization. Thus, while one may see exchange occurring over the long term, it is not a prime-mover but it is changes in evidence of production, transfer, and consumption of non-local goods that inform theoretical models of prehistoric change.

Exchange concepts reflect the current theory

Forty years ago, advances in technical analysis in archaeology, in particular geochemical sourcing, initiated several decades of research into exchange by archaeologists. Following the dominant theoretical approaches of the time, adaptationalist or managerial models held that socio-political change was stimulated by factors that impacted the entire cultural system. Such changes could be stimulated by a combination of factors, including external pressures and internal pressures. External pressures include resource stress, drought, and warfare. Internal pressures include greater efficiency in organization despite larger population levels, irrigation, and organizational complexity due to circumscription.

More recent theoretical approaches focus on social and political strategies prioritize the active role of individuals in the process of political change. The role of commodity exchange in the onset and dynamics of socio-political complexity connects the exchange behavior documented by anthropologists with the long term changes that underlie the archaeological evidence of exchange in prehistory. Leveling mechanisms among hunter-gatherers promote intergroup sharing and are especially prominent when resource predictability is low. With greater resource predictability, and especially when resources are intensifiable, these leveling mechanisms often begin to break down and social differentiation is observed.

Exchange is thought to have been one of a number of interacting behaviors by "aggrandizing" individuals that had the indirect result of institutionalizing social inequality (Clark and Blake 1994;Flannery 1972;Hayden 1995;Hayden 1998;Upham 1990). What were the socio-political contexts that permitted individuals to differentiate themselves, and how did individuals pursuing their interests result in the long-term changes observed archaeologically?

Early leaders

While early social hierarchy emerged from the so-called egalitarian contexts of small-scale societies, Wiessner (2002: 233) observes that "hierarchy characterizes the societies of our closest non-human primate ancestors and seems to be deeply rooted in human behavior" and social hierarchy can therefore be considered a "reemergence" of hierarchy. Egalitarianism is not the "tabula rasa for human affairs on which aggrandizers impress their designs" (Wiessner 2002: 234); rather, it is the result of coalitions and complex institutions of weaker individuals in society that curbs the ambitions of the strong and results in egalitarian structures that were as complex and varied as hierarchical power structures. Wiessner argues that cooperative behavior, such as elaborate exchange relationships, in egalitarian institutions fostered ideologies of coalition building and cooperation in kinship-based networks that extended far beyond local groups. While the egalitarian ethos constrained the competitive activities of aggrandizers, these institutions also provided powerful tools to the cooperative structure that could be used to the advantage of aggrandizers. Exchange has particular significance in agency models that strive to explain how the activities of aggrandizers can result in institutionalized inequalities because exchange can contribute to an understanding of the relationship between structure and agency at this juncture.

Aggrandizers had to work within powerful institutional boundaries that already existed in egalitarian societies in order to forward their interests. The changing nature of exchange, embedded within shifting institutional contexts, complements the emphasis on alienable commodities (Appadurai 1986, see Section 2.2.2). Aggrandizing individuals operate within institutional contexts, indeed their vehicle to promotion is social recognition, yet the ability to organize resources to obtain lower costs for particular items benefits aggrandizers and their supporters. Exchange is a universal feature of human societies, and studies that document the diversity of forms that exchange takes in contexts of early social ranking can shed light on the specific strategies used by aggrandizers that resulted in institutionalized inequality (Clark and Blake 1994).

Prehistoric institutions

Beginning with settlement pattern studies explored by Julian Steward, processual archaeologists often assume regional perspectives that emphasized social and organizational processes (Willey and Sabloff 1974). Building on Polanyi's observation that fundamental aspects of human institutions are economic, archaeologists understood that documenting the regional distributions of artifacts resulting from prehistoric mobility or exchange could contribute to reconstructing past societies. Archaeologists can use direct evidence from the production and consumption of archaeological materials and inference about the likelihood and form of prehistoric exchange to point to the institutional contexts of the ancient economy.

In Polanyi's (1957) seminal article outlining the substantive approach, "The economy as an instituted process," the economy is characterized in terms of two linked properties. First, there is the material process by which items are produced, circulated, and consumed; second, there is the economic form organized around socio-political relationships that arranges interactions diachronically and spatially. In this context, institutions serve as rules and obligations connecting human organizations around the process of producing and circulating goods. The implication is that an archaeological study of variation in prehistoric economies requires that archaeologists can document differences in the institutions that structured past economies.

Many contemporary theoretical approaches downplay the importance of structural analyses in favor of agent-based models, however anthropologists using New Institutional Economics (North 1990) are emphasizing the interdependence of institutions and economics and the implications for activities of individuals (Acheson 2002;Ensminger 2002). Douglass North (1990: 3) defines institutions as "the rules of the game in a society or, more formally, the humanly devised constraints that shape human interaction". This view considers how institutions developed from the decisions of individuals over long periods of time, affecting transaction costs through the benefits of coordinated activity. "Based on the advantages of lower transaction costs in commodity flows, [these anthropologists] argue that political and social institutions developed to regulate commodity flows, maintain regional peace, and guarantee contracts" (Earle 2002: 82). In this perspective, institutional complexity developed as rules to govern the economizing nature of individuals, and the emergence of such institutions should be correlated with increasing quantities of commodity exchange in prehistory. The perspective that argues that volume of exchange should correlate with increased social complexity has roots in theories of progressive evolution (Childe 1936), adaptionalist views (Steward 1955), and the managerial role of chiefs (Service 1962).

However, a positive correlation between evolving institutional complexity and a uniform increase in volume or variety of exchange in prehistory is not supported empirically (Brumfiel 1980;Hughes 1994;Kirch 1991). That is, contrary to the evolutionary expectations of some theorists, the volume or variety of goods transferred does not necessarily reflect the political or institutional complexity in a given society. Perhaps some of this inconsistency is the result of elite control of the circulation of commodities as proposed by Appadurai (1986: 38). Earle (1994: 420-421) observes that on the whole, the archaeological evidence is characterized by a great deal of variability in the types of goods exchanged, the volume of exchange, and the social contexts of exchange. In order to address this variability in an evolutionary framework, Earle suggests that exchange should be considered in terms of two categories, the subsistence economy and the political economy[1](Johnson and Earle 2000), with exchange taking different forms in each category of the economy. The exchange in these two forms of economy correspond largely to the distinction discussed earlier between ordinary goods and prestige goods where, according to Earle, political strategy is advanced by elites by, among other things, the manipulation of exchange relationships.

In a non-evolutionist application of New Institutional Economics in anthropology, Wiessner (2002: 235) differs from North in arguing that transaction costs for exchange are actually high in small-scale societies due to the close relationship between social and economic transactions; there is less neutral space for "unembedded" economic behavior with their associated overhead costs. In such contexts egalitarian institutions developed to foster trust and make interactions more predictable.

In non-market economies in which kin-based exchange systems play an important role in reducing risk (Wiessner 1982;Wiessner 1996) the goal of exchange is to be covered in times of need. In this context, the social and the economic are closely intertwined (Mauss 1925) and it is undesirable for returns to be stipulated as to time, quantity, or quality (Sahlins 1972). The most valuable information in such exchanges is the details of the partner - what he or she has to offer and will offer over the long run (Wiessner 2002: 235).

Elaborate institutions regulating behavior are not new, argues Wiessner, but if there is a weakening in the egalitarian prohibition against the accumulation of wealth or power the "alchemy of ambition" (Wiessner 2002: 234) drives a few individuals to seek preferential access to resources. In contexts of regional packing and circumscription it is argued that hierarchies emerge (Brown 1985;Johnson 1982) that are perhaps founded on the control of labor and surpluses, and instituted through ritual (Aldenderfer 1993;Hayden 1995)

Materialist perspectives hold that economic gains are used to bring about changes in the social order, and that these changes are then legitimized and perpetuated through ideology. These economic gains are generally achieved through intensification of production and through finance organized by ambitious individuals (Boone 1992;Earle 1997;Hayden 1995). Clark and Blake (1994: 17), building on practice theory (Bourdieu 1977;Giddens 1979), describe a model whereby institutionalized inequality is the unintended outcome of political actors competing for prestige by using strategies that match the self-interests of their supporters. Ultimately, these strategies may develop into redistributive institutions that appear to build on the social-leveling mechanisms described by Wiessner (1996), but operate on a larger scale and result in political advantage for redistributing leaders and their allies. In other words, it is institutions themselves that form the basis for leveling mechanisms, and it is institutions that are transformed into vehicles that serve to, in part, legitimize social inequalities.

An important temporal component to exchange is connected to institutions as well because transactions involve anticipation and scheduling. As Colin Danby (2002) argues, most transactions in neoclassical economic analyses in anthropology are considered as synchronic "spot transactions" of commodities, while long term interpersonal relationships enter the domain of gifts in a gifts: commodities dichotomy. The temporality of reciprocation is a means by which economic transactions are embedded inside of social calendars, but various socially-mediated methods of extending credit are well-established and probably an ancient manner of precipitating exchange in market-based transfers as well.

Pastoralism, caravans, and social inequalities

The domestication of cargo-bearing animals contributed several important elements that transformed the nature of regional exchange relationships. First, there are some cross-cultural commonalities in the structure of contemporary societies practicing pastoralism, and it is probable that these factors had some role in prehistoric pastoral societies as well. Second, cargo-bearing animals transform the costs of transport and, consequently, the nature of long-distance interaction. Finally, the structure of wealth in animal herds conveys particular scalar advantages to powerful kin-groups that possess large herds. These factors condition long-term transformations such as sedentism, the nature of food production, and the institutionalization of social inequalities. These issues will be explored in three sections: household level articulation with agriculturalists, wealth accumulation among herders that is limited by risk and pasture, and caravans and the organization of pastoral labor.

Household level articulation with agriculturalists

An important structuring principle to pastoralist exchange is that herding systems are not economically independent because humans must consume a sufficient diversity of major food groups for nutritional reasons; a condition known as non-autarkic (Khazanov 1984;Nielsen 2000). Depending on available wild plants, herders may acquire a portion of their non-animal products from gathering activities but the more common solutions involve a mixed agro-pastoral strategy or articulation with agriculturalists. Furthermore, herders with animals capable of bearing loads are the natural agents for facilitating this articulation with agriculturalists (Browman 1990;Flores Ochoa 1968). Thus, exchange relations are a basic necessity for dedicated herders. For herders with cargo animals, the transport of exchange goods in some capacity was likely a regular feature of pastoral household economies, and to become more common and less laborious in terms of quantity of goods exchanged due to assistance of cargo animals. As pastoralist households are not autarkic, due to the need for non-animal foods on a regular basis, households usually have cargo animals as part of their herd and relatively brisk exchange networks are likely to develop between households without the need for elites, administrative oversight or investment from super-family organization.

Limitations to accumulation by herders

Inequalities are evident in most pastoral societies as owners with large herds are better able to maximize by grazing all available lands when conditions allow and hiring additional help with herding tasks like shearing and butchering. Furthermore, large herds can reproduce more quickly, are better able to survive hardship, and better maintain a minimum herd size threshold for viability. Nevertheless, pastoral wealth is widely recognized as unstable due to the overall vulnerability to drought, disease, parasites, predators, theft, and accidents that can cause declines of over 50% in a given year (Khazanov 1984: 156;Kuznar 1995;Nielsen 2000: 42;Salzman 1999). Herders mitigate this risk by diversifying production, maintaining extensive exchange networks, holding access to grazing land in common, and utilizing other institutional means of risk reduction, such as the redistribution mechanism of suñay among Andean pastoralists (Flannery, et al. 1989).

A significant pastoral institution that appears to function as a leveling mechanism is the corporate ownership of pasture. While herds are typically held by individuals or kin-groups, herding is spatially extensive rather than intensive, and access to pasture in herding societies almost universally requires community negotiation (Ingold 1980;Khazanov 1984;Nielsen 2000: 46-51). Among pastoral societies that do not store fodder the carrying capacity of the land, and therefore the intensifiability of production, is limited by the season with the lowest productivity (Nielsen 2000: 43). Finally, in some regions of the world, such as the Andes, modern herds are bilaterally inherited which serves to prevent accumulation in specific descent groups (Lambert 1977;Webster 1973: 123). Thus, herding does not organizationally contain the seeds for social inequality, but intensified pastoral wealth in the form of very large herds has been documented as one principal form of investment in ethnohistorically known hierarchical societies in herding regions.

Caravans and the organization of pastoral labor

Pastoralist societies that organize into seasonal trade caravans share structural characteristics; some of these characteristics tend towards promoting social inequalities and others that counter-act the tendency (Browman 1990). The organizing of a trade caravan is often simplified among dedicated pastoralists because pastoralism is relatively efficient in the use of labor, and the herding and caravanning schedules can be prioritized (Nielsen 2000: 44-45). A single herder can monitor hundreds of animals on a typical, uneventful day of pasturing without a great deal of effort, and as physical labor is low as compared with agricultural tasks, children and the elderly often contribute and broaden the herding labor pool. As a consequence, during caravan season the loss of several capable family members (usually adult men) to the caravan journey for weeks or months during a single year may not unduly hamper the productivity of a household of dedicated pastoralists.

As mentioned above, all pastoral households must acquire non-pastoral products through diversification or exchange, however the ability to organize a caravan inherently favors the wealthier herders for several reasons.

(1) Herders with large herds are more likely to have a sufficient number of hearty animals capable of enduring long journeys with cargo.

(2) Caravan animals provide the mechanism of transport. Therefore, for direct exchange consisting of spot transactions, pastoralists must initiate the trade opportunity by traveling to their trade partners with a sufficient surplus of goods to acquire goods in exchange.

(3) The rewards of such trade caravans accrue differentially, allowing those who regularly participate in such ventures to acquire access to non-pastoral resources, a more extensive social network and perhaps fictive kin among distant trade partners, and enhanced prestige among their community.

While some elements of dedicated herding societies favor differential accumulation of wealth in the form of large herds, diversification of the resource base, and extensive trade networks, the realities of high risk to pastoral wealth and low intensity of land use affect all herding households equally to the extent that they dedicate themselves to pastoralism. Thus, while redistributive mechanisms and corporate tenure of pasture serve to stabilize pastoral systems, the structure of herding systems also provides a few opportunities for strategic advantage to more opportunistic and aggrandizing elements of prehistoric society. In addition, despite the risk in herding systems the ownership of a large herd may directly confer prestige on pastoralists (Aldenderfer 2006;Hayden 1998;Kuznar 1995: 45), and inequalities in pastoral wealth can be channeled into more enduring and intensifiable avenues such as increased exchange (ultimately resulting in large trade caravans) or a mixed agro-pastoral strategy. As a pastoral economy with cargo transport capabilities first takes hold in a region, increased social differentiation may reflect a co-evolution between more extensive exchange relationships, greater sedentism, population increases, and larger population centers.

2.2.4. Definitions of exchange

Studies of exchange can contribute to understanding human behavior because, more than any other species, humans have possessions and shift them between individuals. A person can acquire an object of wealth either by producing it or exchanging for it. In the terms used by economic anthropologists, exchange takes a number of forms in social interaction. Wealth is the objective of a person's labor and is therefore culturally determined. Markets refers to a market-based economy where prices reflect supply and demand (LaLone 1982: 300), as is not to be confused with aggregated transfers of various forms occurring in marketplaces. Exchange or trade are commonly used terms for processes referred to more generally by economists as transfer or allocation (Hunt 2002). Commodities, goods, and products are used here synonymously here and do not imply exchangeability or alienability.

Polanyi and the economics of exchange

The principal forms of economic organization outlined by Karl Polanyi (1957) - reciprocity, redistribution, and market forces - have been widely used in anthropological discussions of exchange. Paul Bohannan describes the relevance of these economic modes to exchange:

Reciprocity involves exchange of goods between people who are bound in non-market, non-hierarchical relationships to one another. The exchange does not create the relationship, but rather is part of the behavior that gives it context.

Redistribution is defined by Polanyi as a systematic movement of goods towards an administrative center and their reallotment by the authorities at the center.

Market Exchange is the exchange of goods at prices determined by the law of supply and demand. Its essence is free and casual contract (Bohannan 1965: 232).

In principle, the price-fixing aspect of market based exchange has an integrative effect and entails communication between segments of the exchange sphere. For the trader, market exchange involves risk and potential profit. For the producer, the consumption patterns and fluctuations in demand should be sensed all the way back in the contexts of production. Market articulation in land-locked regions of Asia and North Africa provided the initial contexts for large-scale caravans in the Old World. With caravans perennially under threat of robbery or obligation to pay duties for crossing sovereign land, the "nomadic empires of the Turk, Mongol, Arabic, and Berber peoples were spread out like nets alongside transcontinental caravan routes" (Polanyi 1975: 146-149). In contrast to market mechanisms, Polanyi also described exchange modes of institutional or administered trade, where material needs were satisfied through the movement of goods but the practice was not motivated by "profit" for merchants in the market sense of the term but rather to meet institutional goals (Salomon 1985: 516;Stanish 1992: 14;Valensi 1981: 5-6). In this type of trade, value and equivalencies are established by political authority or by precedent.

Characteristics of a market economy

Markets are of particular interest in this discussion because while market principles, to a certain extent, underlie all formal economic approaches in anthropology, market-based economies are far from universal in the premodern world, even among state-level societies. A basic definition of a market is "the situation or context in which a supply crowd (sellers) and a demand crowd (buyers) meet to exchange goods and services" and where the market principle is operating (Dalton 1961: 1-2). Three characteristics used by Earle to evaluate the evidence for market-based exchange in the Inka state include: (1) The importance of specialized institutions of production and exchange divorced in their operations from other institutional relationships; (2) The development of a medium of exchange to facilitate the systematization of exchange values; (3) The percentage of goods utilized by a household that are obtained by exchange (Earle 1985: 372-373).

The presence of exchange institutions, either as bustling marketplaces or distributed as "site-free" exchange houses, have a characteristic described by Earle (1985: 373) as a context where "non-exchange relationships, such as kinship and political ties, will not unduly constrain choice". The alienability of products, the strong influence of price motive and the detachment from production and other social linkages, underlie many of the features of these proposed institutions. The consensus among Andeanists is that during Inka domination, and probably during the preceding periods, market-based economies were not found in the central and southern Andes with a few exceptions (Earle 2001;LaLone 1982; but see href="/biblio/ref_2005">Salomon 1986;Stanish 2003).

The location of transfer becomes important with respect to price-fixing markets. In aggregations the public nature of the contact and the circulation of information is quite different from isolated exchanges. These issues are linked to the spatial and temporal configuration of exchange in market economies because just as periodic gatherings, central places, and rank-size geographic relationships serve to distribute goods in some settlement systems, these aggregations serve to distribution information about availability of products and changing prices to buyers and sellers (Smith 1976;Smith 1976). When exchange takes place in a private courtyard rather than a public marketplace then there is reduced risk of the neighbor overhearing the barter exchange value offered to another (Blanton 1998;Humphrey and Hugh-Jones 1992). Greater public visibility and monitoring in market contexts might be expected, and greater privacy, interpersonal negotiation, and temporal depth to exchange relationships in private barter exchange configurations.

Variations on Modes of Exchange

Some scholars have built on Polanyi's four original modes of exchange, others have developed entirely new schema (Smith 1976). Earle (1977: 213-216) argues that Polanyi's (1957: 250) definition of redistribution as "appropriational movements towards a center and out of it again..." is vague and Earle observes that this definition is so broad that it could to apply to economic systems ranging from central storage of goods in Babylonia to meat distribution in band-level hunters. Earle advocates separating leveling mechanisms from institutional mechanisms, where institutionalized redistribution involves wealth accumulation and political transmission between elites across broad regions in the mode of peer-polity interaction (Earle 1997).

Andean political economy

Stanish (2003: 21) expands on Polanyi's system by describing political economy in the prehispanic Andes with deferred reciprocity taking the form of competitive feasting and political support (Hayden 1995;Stanish 2003: 21). Stanish observes that while there was an implicit or explicit (Service 1975) evolutionary sequence going from reciprocity to redistribution and finally to markets, more recent evidence suggests that these modes can co-occur and that the relationships are too complex to collapse into a single sequence.

Types of reciprocity

Sahlins (1972: 194-195) further elaborated on aspects of Polanyi's reciprocal mode with generalized, negative, and balanced reciprocity. Generalized and negative reciprocity are opposite ends of a continuum (see Figure 2-1, above). Generalized reciprocity refers to sharing, altruism, and Malinowski's "pure gift", while negative reciprocity is the attempt to maximize personal gain from the transaction through haggling or theft (Sahlins 1972: 195-196). Polanyi's basic modes of exchange have persisted in economic anthropology for almost fifty years. Some argue that Polanyi's modes of exchange are limiting in that they do not provide a means to analyze precapitalist commercial activity (Smith 2004: 84), however the benefit to Polanyi's exchange modes is that they are sufficiently general to be comparable cross-culturally and the three modes are discrete enough to be, in some cases, archaeologically distinguishable. Furthermore, if commercial activity is unlikely in the study region, as in the prehispanic south-central Andes, Polanyi's modes capture the necessarily economic variability.

Geographical characteristics

Renfrew (1975) considers trade as interaction between communities in terms of both energy and information exchange. Renfrew (1975: 8) tabulated Polanyi's schema as follows

|

Configuration |

Geographical |

Affiliation |

Solidarity |

|

|

Reciprocity: |

Symmetry |

No Central Place |

Independence |

Mechanical |

|

Redistribution: |

Centricity |

Central Place |

Central Organization |

Organic |

Table 2-3. Characteristics of reciprocity and redistribution (from Renfrew 1975: 8).

Renfrew follows with an exploration of the greater efficiency implied by central place organization in terms of material and information exchange. The universality of central place organization in the development of complex political organization worldwide has been called into question in pastoral settings. In the south-central Andes, anthropologists have proposed that alterative paths to complex social organization could have been pursued by distributed communities linked by camelid caravans with the anticipated central place hierarchy not occurring until relatively late, as proposed by Dillehay and Nuñez (1988) and in a different form by Browman (1981).

Renfrew has developed a graphical representation of the spatial relationships implied by each mode of exchange.

Figure 2-2. Modes of exchange from Renfrew (1975:520) showing human agents as squares, commodities as circles, exchange as an 'X', and boundaries as a dashed line.

The exchange modes depicted by Renfrew (1975:520), shown in Figure 2-2, efficiently convey the variety in organization represented by exchange relationships. In some regions of the world, such as the prehispanic south-central Andes, market-based economies are not believed to have operated which modifies one's expectations for the activities of traders. The full suite of these ten modes is not expected in any one particular archaeological context worldwide, but the figure serves to underscore the complexity of isolating particular types of exchange based on archaeological evidence. Furthermore, these modes are not necessarily mutually exclusive, as some of these modes may have been operating simultaneously unless restrictions on production, circulation, or consumption of goods were in place.

Exchange network structures

Based on geographer Peter Haggett's (1966) work, network configurations can be used to describe the characteristics of interaction that resulted in the distribution and circulation of goods. In describing Andean caravan transport, Nielsen (2000: 73-74, 91) uses the following terms: (1) distance that goods are transported; (2) segmentary vs. continuous - in segmentary networks a given node is connected to a small number of other nodes, while continuous networks each node is connected to all other nodes; (3) convergent (focalized) vs. divergent (non-focalized) - in convergent networks the individuals participating in exchange, and the goods they transport, tend to concentrate in a small number of central places or exchange locales.

Reciprocal exchange relationships that take the form of down-the-line trade may be described as continuous networks when these mechanisms serve to move goods between ethnic groups and across regions. Centralized political control by elites and true market mechanisms might result in network convergence at central places (Smith 1976). To Nielsen's third set of terms, convergent (focalized), divergent (non-focalized), one may add diffusive to describe the pattern of a single type of item radiating from the center to the surrounding region as occurs with obsidian.

Figure 2-3. Network configurations.