4.1.2. Lower elevation biotic zones: Study Area Blocks 3 and 6

Beginning with the lower elevation part of the survey area and moving upstream, the vegetation of the Colca valley above Tuti consists of low grasses dominated by the ichuvariety during the dry season. The Colca River is relatively low gradient in this area, and two or three levels of natural river terraces are evident along the valley margins. The geography of the zone is dominated by the fact that the confluence of two large river systems (Colca and Llapa) occurs here. This area holds the largest settlements in our study area, but both agriculture and pasture appear marginal in immediate area of these towns. Rather, the settlement of the upper river valley seems to reflect the importance of the articulation between the main Colca valley and the broad altiplano. The village of Sibayo rests precisely at the main confluence of the Colca River and the Llapa River, and as is evident in the Shippee-Johnson expedition, Sibayo has long served as a principal modern ingress to the Colca Valley until the Chivay-Arequipa highway was completed (Shippee 1932).

Settlements

The bulk of the contemporary populations in the study area reside in towns in block 3 established during the colonial period that are distributed along the Colca river. The largest settlement inside the study area is Callalli, a town with a 1993 population of 1295 persons, and across the Colca River the population of the town of Sibayo is 508, and upstream in Block 5 the cooperative of Pulpera numbers 85 residents (I.N.E.I. 1993). These towns are primarily service centers and district seats for widely distributed populations with an economy based largely on pastoral products, and on extensive interaction through trade with their wealth in camelid herds, and have long resided in rural hamlets and herding outposts. Callalli and Sibayo first formed as part of the sixteenth century reducción of the Yanque Collagua, and in the colonial period the province of Collaguas (Caylloma) held three-quarters of the livestock in all of Arequipa (Cook 1982;Manrique 1985: 95-96). The dominance of the herding economy in these upper valley towns is evident in the 1961 census where both Callalli and Sibayo populations are reported as 93% "rural", while the average percentage for all nineteen towns in the Colca census, including large and dense agricultural communities downstream, was only 52% "rural" (Cook 1982: 44).

These early villages also formed an important source of labor for colonial mining ventures in the Cailloma region (Guillet 1992: 25-27). Mercury and copper were mined between Callalli and Tisco (Echeverría 1952 [1804]) and Lechtman (1976) reports a structure in Callalli known as " La Fundición" that is described as "stone metal smelter, probably colonial, said to be for copper smelting: mineral, scoria on surface". A location known as "Ccena" or "Qqena" is described as having "metal smelters near a pre-Spanish occupation site: mineral, scoria, surface sherds" (Lechtman 1976: 11). The toponym "Ccena" can be found close to the Llapa and Pulpera stream confluence upstream of Callalli. These historical smelters were not encountered during the course of our survey in this particular area.

Pyrotechnical installation

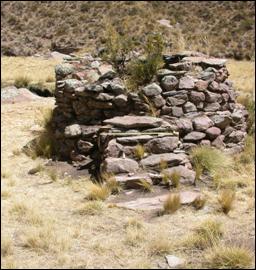

One structure ([A03-842], Figure 4-8) was identified in the course of the 2003 survey that appears to be of colonial period construction and it appears to have some kind of pyrotechnical function (B. Owen 2006, pers. comm.). The structure has two doors in the lower area, apparently providing access to the lower furnace. The internal lower construction is built of thermally altered stones and has a cracked lintel. A variety of pyrotechnical structures are known in the south-central Andes (Van Buren and Mills 2005) that were used to heat lead, silver, or copper, and other oven types (e.g., pottery, bread) are known in the region as well. Slag or other evidence of smelting was not encountered in the soils adjacent to the structure, however, although the building is immediately adjacent to a stream channel and such materials may be eroded or difficult to detect.

Figure 4-8. Exterior and interior of probable colonial pyrotechnical structure at Achacota near Pulpera, upstream and south of Callalli [A03-842]. One meter of exposed tape is visible in each image.

Vegetation and dryland agriculture in the study area

The Callalli area consists primarily of high elevation grassland punaecology (1973). Dry bunch grasses are available much of the year in this area, but during the wet season (austral summer) a greater variety of grasses become available and herds are brought to the valley to exploit the pasture of chilliwuaand llapagrasses.

Callalli and Sibayo lie in the upper reaches of agriculture at this latitude and evidence of abandoned fields are visible in the upper valleys. Plants like tubers, oca, and chenopodium were historically viable at this altitude (Echeverría 1952 [1804]), although microclimatic variability is influential in these conditions of marginal dryland agricultural production. Guillet (1992: 24) cites evidence for climate change from historical sources that describe the cultivation of maize above the current limits for this crop, and coca, membrillo, and peppers on terraces that lie at altitudes where these crops are not feasible today. Wernke (2003: 51-52) considers the significance of climate change evidence from ice cores in mountain ranges to the east for Colca valley culture history and agriculture.

In Markowitz's (1992) ethnographic study at Canaceta, a village at 4000 masl and approximately 12 km upstream of Callalli, villagers explained that they had formerly engaged in agriculture at this altitude, but that they had recently abandoned the practice due to lack of rainfall. She observes that practicing a mixed subsistence system of agriculture and pastoralism was an important cultural ideal in the Canaceta, but that in recent years due to changes in the climate and in economic circumstances they had increasingly become specialized on pastoral production complemented by exchange (Markowitz 1992: 48). Under modern circumstances there is probably not a very high return on labor invested in agriculture in this area as the increased economic integration, and an improved transportation infrastructure with intensive farming areas at lower elevations, has further induced residents towards specialized economic practices. The current distribution system emphasizes pastoral production in the highlands and higher yield agriculture on lands at lower elevations.

Figure 4-9. Tuber cultivation at 4200 masl surrounded by large tuff outcrops.

In the course of survey in 2003 cultivation was observed in a few high altitude locations, such as the upper reaches of Quebrada Taukamayo. The plots were at 4200 masl in a north-north-east facing (10°) aspect and a mild slope (8°). The area is relatively sheltered by the presence of lava tuff flows (see Figure 4-9) that may have had a temperature moderating effect acting like large terrace stones that are known to reduce diurnal variation by absorbing heat during the day and releasing heat at night in the immediate valley microclimate (Schreiber 1992: 131).

Flora and fauna

Important flora and fauna to residents of the Upper Colca region include the following (Gomez Rodríguez 1985;Guillet 1992: 130;Markowitz 1992: 42-44;Romaña 1987;Tapia Nuñez and Flores Ochoa 1984). Major flora comprise grasses such as Chilliwa( Calamagrostis rigescens), a frost-resistant perennial grass that thrives during the rainy season and in bofedales, grazed by a wide range of animals and also used for roof thatching. Other important puna pasture grasses include llapa, malva, sillo, and paco,though these are principally consumable by herbivores only during the rainy season. Ichu/ Paja( Stipa ichu) is a common grass used for thatching. In the higher elevation bofedales one can encounter parru, a grass preferred by alpacas. Wild fruits are gathered seasonally by locals including locoti(cactus fruit), q'ita uba(wild grapes), and sanquayo(a plant related to chirimoya) (Markowitz 1992: 43). In the high elevation area of the obsidian source yareta( Azorella compacta), a green, flowering cushion plant is one of the few flora that grow in the unirrigated areas of this harsh volcanic terrain. In addition to animal dung, dried yaretais the only dense, combustible fuel widely available above 4500 masl. As a local herder, T. Valdevia demonstrated, the cushion plant will burn when it is kicked over and allowed to dry out for several weeks. Drought and cold-resistant shrubs, including tolaand cangi, are valuable sources of firewood in the punatoday, though the shrubs are over harvested in many areas.

Fauna species include a number of birds that are hunted for their meat including the Grey Breasted Seedsnipe known as puko elquio( Thinocorus orbygnianus), partridges ( pishaq), and the guallata,the large white Andean Goose (Chloëphaga melanoptera)(Hughes 1987;Markowitz 1992: 43) .Several Andeancondors ( Vultur gryphus), for which the Colca is renowned, flew repeatedly near our work at the Chivay obsidian source in 2003. Wild mammals observed in the study area include viscacha( Lagidium peruana), tarucadeer ( Hipocamelus aticensis), and the wild camelid vicuña (Vicugna vicugnaor Lama vicugna).Thetrout found in the streams represent an important food source, but these fishes were introduced in the nineteenth century.