Site level composition from multiple sources

When raw material is available to consumers from several competing sources, investigators have used the relative quantity of materials from the different sources at individual sites to gain insights into ancient exchange. Broad exchange relationships are frequently inferred from the presence of obsidian from a distant source. When material from several rival obsidian sources are represented, either strongly or weakly, in different phases at a site, the cause of the changes in representation is often attributed to shifts in the geography of regional political or economic relationships. Geographical explanations are invoked when there is a clear deviation from the LMD, and yet evidence of significant in-situ political change is not found in investigations among studies in Mesoamerica (Zeitlin 1978: 202;Zeitlin 1982) and the Near East (Renfrew 1977: 308-309).

Changes in the mechanisms of exchange, rather than simply geography, are attributed to changes in the source composition from different sources when socio-political changes are perceived by investigators. Studies have inferred redistribution occurring when sites that act as central places (Christaller 1966 [1933]) at the top of the settlement hierarchy have disproportionate quantities of non-local materials irrespective of their distance from the source. This phenomenon has been discussed for Tikal (Moholy-Nagy 1976: 101-103;Sidrys 1977).

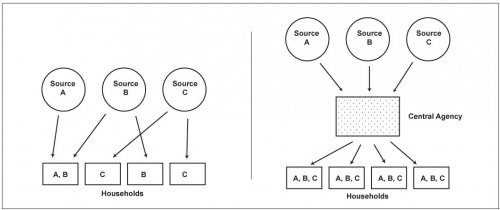

When sourcing studies are conducted at the scale of the household unit, though it is often labor intensive and costly to conduct proveniencing studies to an extent that are statistically meaningful, it is possible to discern convergence patterns that can be connected to exchange mechanisms (Pires-Ferreira and Flannery 1976;Santley 1984;Torrence 1986: 35). The most common application of evidence of variability between households in source composition is to infer redistribution from the presence of low inter-household variability in source composition.

In a reciprocal economy where individual households negotiate for their own obsidian, we would expect a good deal of variation between households, both in the sources used and the proportions of obsidian from various sources. Conversely, in an economy where the flow of obsidian is controlled by an elite or by important community leaders, who pool incoming obsidian for later distribution to their relatives, affines, or fellow villagers, we would expect less variation and more uniformity from one household to another (Winter and Pires-Ferreira 1976: 306).

The concept is been depicted in a graphic from.

Table 2-4. Household composition of raw materials should vary with different types of exchange. On the left, individual households acquire source materials more directly, on the right pooling and redistribution results in greater inter-household consistency in raw material composition (Winter and Pires-Ferreira 1976: 311).

This approach was influential in Mesoamerica (Clark and Lee 1984;Santley 1984;Spence 1981;Spence 1982;Spence 1984 ) where the technology of transport did not change significantly except for perceived changes in the form of boat technology. Transport changes could significantly impact the inter-household diversity of source composition in places, such as the Near East, where caravan exchange networks followed from the domestication of pack animals (Wright 1969). The impacts of caravan exchange on artifact variability has long been discussed in the Andes (Dillehay and Nuñez 1988;Nuñez and Dillehay 1995 [1979]), although household-level sourcing data has not been available to date.