Horizontal complementarity

Soon after Murra published his 1972 paper about vertical complementarity, researchers began noting that vertical complementarity is only one of a number of strategies employed in the Andes. A different kind of geographical interaction pattern, one that stays within broad regions such as the altiplano or the littoral, has been called horizontal complementarity. Contrasted with Murra's vertical complementarity model, in horizontal complementarity polities would directly control many parcels in a given niche. Here, the adaptationalist argument is somewhat less obvious since a horizontal complementarity strategy seems redundant unless particular resources were only available in one sector of a given horizontal territory. This phenomenon could reflect a cultural mechanism for the continued social integration of communities distributed widely across a vast region. An analogous situation can be observed in the culturally-constructed Yanamamö trade for ceramic wares, maintained to provide a social catalyst for villages to come together for feasting and marriage-making, despite the risk of conflict and treachery (Chagnon 1968).

Relations of horizontal complementarity between coastal valleys have been observed on the littoral (Netherly 1977;Rostworowski 1977;Shimada 1982), and for the higher altitude altiplano area where this kind of organization is referred to as the "altiplano mode of economic integration" (Browman 1977) and, to a lesser extent, the modern "extended type of Andean zonation" (Brush 1977: 12-16;Gade 1975). The extended type takes place in regions of expansive, contiguous production where exchange forms the basis for circulating products from other zones. In the expansive altiplano where there are fewer impediments to travel and, with the domestication of camelids, relatively low transport costs with cargo animals, materials may have been conveyed over substantial distances.

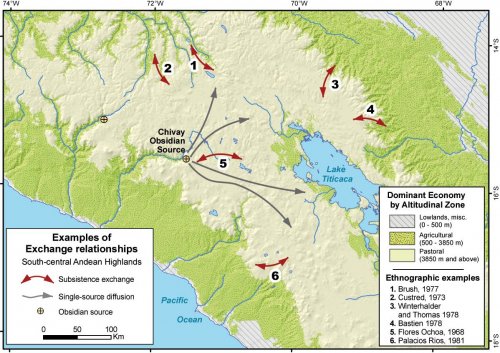

Figure 3-4. Subsistence exchange for products by ecozone versus single-source, diffusive goods.

A general schematic of these contrasting relationships is shown in Figure 3-4. While there is a great deal more complexity and variability to economy and exchange than is communicated in Figure 3-4, for example tubers are grown in the high elevation zones and herding does occur below 3800 masl, the purpose is to highlight the contrasting network characteristics. These two characteristics include

(1) Subsistence exchange.The acquisition of products available by zone contrasts

(2) Diffusive.The network for goods that radiate diffusively, such as obsidian and salt.

While the mixed agropastoral strategies are also very common, particularly in ecotone areas such as the puna rim, the subsistence exchange that articulates dedicated pastoralists with agriculturalists has been documented ethnographically in many studies of which only a selection are shown in Figure 3-4 (Bastien 1978;Brush 1977;Custred 1973;Flores Ochoa 1968;Palacios Ríos 1981;Winterhalder and Thomas 1978).

Ecological complementary has long served to transfer goods between ecozones, however the movement of goods laterally through areas of homogeneous resources, such as horizontal complementarity across the puna, implies other mechanisms of transfer. In addition to strategies described previously, it has been proposed that large periodic markets are a possible solution to the problems of social and economic integration among agropastoralists living in widely distributed settlements.

Browman (1990: 405-411) reviews the evidence for prehispanic and colonial period markets in the Peruvian and Bolivian altiplano. The colonial period aggregations in the Andes are products of historical circumstances, however Browman's evidence suggests that periodic fairs in some form were a feature of the prehispanic economy. While evidence concerning the actual goods exchanged at periodic fairs during the prehispanic period is scarce, these events could have been an effective way for obsidian to have been distributed in highland Peru and these fairs will be discussed in more detail below. Seasonal or annual gatherings are also ethnographically known among foragers in arid regions of the world with low population densities (Birdsell 1970: 120;Steward 1938). Social aggregations in some form can be expected to date back to the foraging period and these aggregations probably included, among other activities, the exchange of goods.