7.1. Goals of the analysis of production

Tthe aim of this analysis was to document changes in lithic reduction strategies over time in the vicinity of the Chivay obsidian source. The research focus was on obsidian procurement and production, and here the emphasis is placed on detecting changes in the morphology of flakes and cores that were collected both in the source area and the blocks immediately surrounding the source. As quarry workshops frequently do not include recognizable artifact types, the focus of this analysis was on the changing nature of reduction through prehistory at the source using technical analysis of flakes, cores, and tools both at the obsidian source and at sites further away from the source.

Evidence from consumption contexts frequently contains a high percentage of artifacts discarded at an advanced stage of reduction or broken in use, however the typical production site in a quarry zone overwhelming consists of non-diagnostic flakes and cores discarded during production. In other words, such areas are rich in negative evidence concerning the artifacts that were not transported and consumed. For example, one could assume that the goal of obsidian reduction in the Early Pastoralists and Late Prehispanic times was the production of type 5b and 5d projectile points, as those were the dominant forms for bifacially-flaked obsidian tools in the time periods covered by the excavated sequences. However, this focus on projectile point production ignores the wide utility of simple obsidian flakes. In other words, a variety of potentially useful flake forms could be struck from a high quality core, and therefore procuring and exporting cores may have been a central goal at in the obsidian source area.

Rather than to attempt the construction of linear sequences linking nodules and cores with specific artifact forms, the focus here is on describing attributes of assemblages per level in order to document changes empirically. Comprehensive sequence models such as chaîne opératoireoften incorporate procurement and quarry production in the earliest stages of a more elaborate sequence. However, detailed examinations of the initial stages of production are typically often not addressed in these comprehensive sequence models because the focus is on behavioral context of consumption and resharpening (Section 2.4.4). While implementing a chaîne opératoireapproach is occasionally attempted at quarries (Edmonds 1990), the value of constructing "chains" appears to be limited at quarry workshops where the bulk of the evidence is constituted by only the first few "links" in the chain. Archaeologists have presented more truncated sequential approaches for bifacial reduction at obsidian sources (Darras 1999: Ch. 7;Pastrana and Hirth 2003), where reduction strategies are largely based on the starting shape and size of the nodule which, in turn, may reflect quarrying behavior and procurement effort. In the present analysis of five stratified 1x1m test units: the quarry pit (1 unit), workshop (1 unit), and two consumption contexts (3 units) the focus here is on describing morphological properties of production and consumption rather than constructing sequences based only five test units.

|

Fraction of Advanced Analysis |

Total Analyzed |

|||

|

Site |

No. |

Percent |

No. |

|

|

Surface |

1289 |

68.5% |

1883 |

|

|

Q02-2u1 |

Source (Corral) |

0.0% |

108 |

|

|

Q02-2u2 |

Source (Pit) |

73 |

66.4% |

110 |

|

Q02-2u3 |

Source (Workshop) |

1487 |

96.3% |

1544 |

|

A02-26u1 |

Taukamayo |

333 |

58.4% |

570 |

|

A02-26u2 |

Taukamayo |

0.0% |

15 |

|

|

A02-39u1 |

Pausa |

0.0% |

15 |

|

|

A02-39u2 |

Pausa |

4 |

13.8% |

29 |

|

A02-39u3 |

Pausa |

166 |

68.0% |

244 |

|

A02-39u4 |

Pausa |

238 |

72.1% |

330 |

|

Total |

2301 |

77.6% |

2965 |

|

Table 7-1. Lithics Phase II analysis showing fraction of artifacts with detail measures.

Nevertheless the lithics analysis of five of the excavation units produced exhaustive empirical evidence. As described in Chapter 5, the Lithics phase II: Advanced analysis stage involved taking up to 30 measures per flake.

Some preliminary sequences can be explored with the workshop data. For example, two principal reduction trajectories appear to have their roots in the evidence apparent in workshop production. These two sequences can be described as (1) "core reduction" and (2) "flake as core reduction".

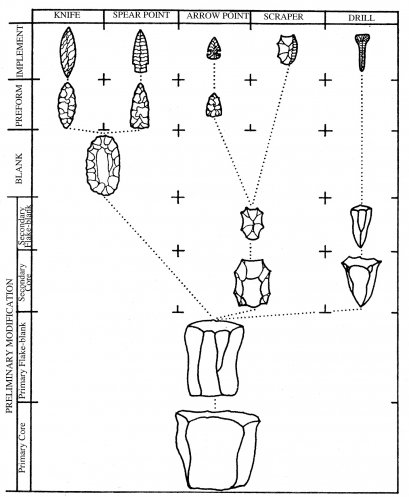

Figure 7-1. Principal lithic reduction in the northern African Gumu-sana assemblage(Bradley 1975: Fig. 1).

Described by Bruce Bradley (1975) in as "secondary core", the flake-as-core sequence begins on a large flake with a single positive percussive feature, but this flake serves as a core for the production secondary flake blanks. In Bradley's example, three possible sequences are described from a single core form, and the variability in sequences is compounded by variability in the size and shape of starting nodules.

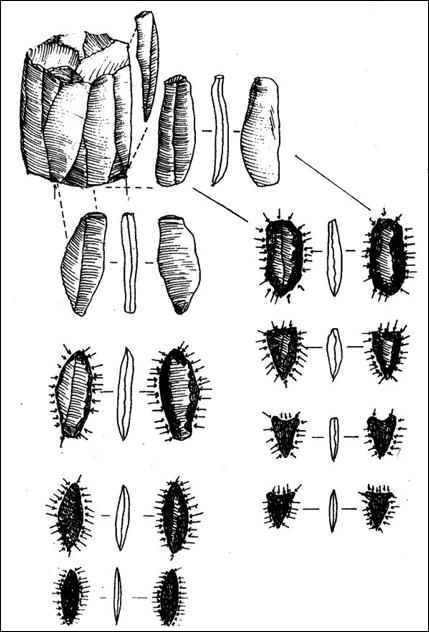

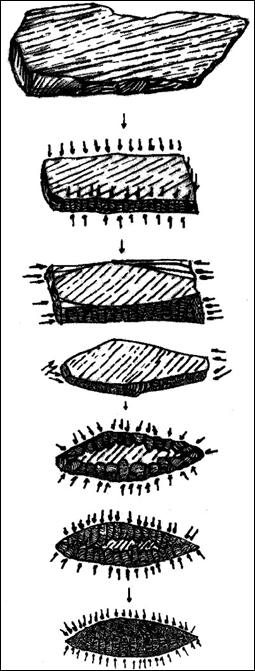

Figure 7-2. Bifacial sequences diverge based on the original nodule form with arrows showing percussion direction (Pastrana and Hirth 2003: 204-205): (a) block nodules for the production of flake-cores, (b) flat slabs of tabular obsidian for shaping preforms.

At the Sierra de las Navajas (Pachuca) obsidian source in central Mexico, both prismatic blade manufacture and bifacial reduction occurred at workshops adjacent to the source. Focusing on the bifacial industry, Pastrana and Hirth (2003) describe two distinct bifacial reduction sequences. One begins on block nodules that are developed into prepared cores, the other sequence exploits the occurrence of long, narrow nodules described as "tabular obsidian". This study underscores the importance of core form variability in the ensuing reduction sequences and it highlights the challenges inherent in reconstructing detailed sequences from quarry workshops based on assemblages that are principally discarded by-products.

In lieu of attempting to develop specific sequences the focus in the Upper Colca project analysis is on describing attributes in Chivay obsidian production and focusing on more general questions.

Principal questions driving the analysis of excavated materials include the following:

- What characteristics of reduction strategies changed through time?

- How did changing availability of raw material through quarrying change the strategies at the workshop?

- How does obsidian production at the quarry area compare with consumption in the immediate vicinity of the Chivay source and with distant consumption in the Titicaca Basin?

These questions frame the research at the Chivay source. The lithic assemblages are approached through quantitative and qualitative description, and also through an investigation of regular change through time at the quarry workshop through clustering of quantitative attributes of cores and flakes.